CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 8, September 2013

306

AFRICA

without early mortality. Various complications occurred in

41.6% (

n

=

5) of patients, with more than half the patients having

a prolonged intensive care unit stay.

Total pericardiectomy, which we defined as peeling the

parietal pericardium between the phrenic nerves anteriorly and

peeling its diaphragmatic surface inferiorly, was achieved in

nine patients. Pericardiectomy was limited (partial) in three

patients in whom the decortication border could not satisfactorily

be extended through the lateral aspect of the left ventricle

because of dense calcific adhesions. Also, fragmented areas of

the epicardium had to be left without peeling and could not be

included within the decortication border in five patients.

Although pre-operative ejection fractions of the patients were

within normal ranges, postoperative LCOS was observed in

seven patients. High rates of LCOS may partly have been due

to structural alterations within the ventricle myocardium, which

had developed due to long-lasting constriction during the chronic

disease period. However, inadequate decortication of the left

ventricle was the most probable reason for the development of

high rates of LCOS, but this could not be totally proven.

The initial approach should include a thorough clinical

evaluation, with pericardiocentesis under echocardiographic

guidance, and heart catheterisation available. The existence of

persistent high intracardiac pressures, despite evacuation of the

effusion, is essential for an accurate diagnosis; ECP was present in

only 6.8% of patients undergoing pericardiocentesis in Sagrista-

Sauleda and co-workers’ study.

2

Effective pericardiocentesis is

of therapeutic importance, especially in the setting of pericardial

tamponade.

ECP has increasingly become a subject of intense research.

Hancock was the first to describe the condition as a particular

form of pericardial constriction, which persists despite evacuation

of the compressive pericardial effusion.

1

Although its prevalence

ranged between 2.4 and 14.8%,

3

Cameron reported the proportion

of ECP to be as high as 24% in patients requiring pericardiectomy.

4

The first prospective study by Sagrista-Sauleda and co-workers

identified 15 ECP patients among 190 with tamponade over

a period of 16 years.

2

In this study, an accurate diagnosis of

ECP was made with combined pericardiocentesis and cardiac

catheterisation. The aetiological spectrum was similar to that

reported in previous studies, with a predominance of idiopathic

cases. Other less-frequent causes included post-cardiac surgery,

tuberculosis, post-radiation and neoplasia. Seven of 15 (46%)

patients underwent pericardiectomy within four months after

pericardiocentesis and two patients died in the early postoperative

period.

Patients with cancer were found to have a high mortality and

low pericardiectomy rate, whereas patients with idiopathic causes

of ECP had a low mortality but high pericardiectomy rate. Also,

four of the six survivors ultimately required pericardiectomy.

2

We concluded that the development of persistent constriction is

frequent in ECP and extensive epicardiectomy is the procedure

of choice in patients with persistent heart failure.

A recent systematic review by Ntsekhe

et al

.

3

identified a

pooled prevalence of 4.5% by applying a random-effects model.

The aetiological spectrum was similar to that of previous ECP

and CP series, although neoplastic and traumatic cases were

excluded from the analysis; 26 ECP patients were identified

among 642 subjects derived from five observational studies. The

TABLE 4. OPERATIVEAND POSTOPERATIVE PARAMETERS

Operative parameter

Value (%)

Complete pericardiectomy

9 (75.0)

Time of operation (min)*

90 (90–120)

Ventilation

>

8 hours

4 (33.3)

24 hours bleeding (ml)*

525 (362.5–837.5)

Re-operation for bleeding

2 (16.6)

Fluid removed (ml)*

875 (500–1350)

Transfusion (1 unit of ES)

5 (41.7)

Arrhythmia

3 (25.0)

LCOS

7 (58.3)

ICU stay

>

3 days

7 (58.3)

ICU stay

>

7 days

3 (25)

Peri-operative mortality

0 (0)

ES: erythrocyte suspension; LCOS: low-cardiac output syndrome; ICU: intensive

care unit.

*Data represented as medians with interquartile ranges.

TABLE 5. RESULTS OF PERICARDIAL TISSUE BIOPSYAND FOLLOW-UP

DATA

Pat-

ient

Aetiol-

ogy

Date of

opera-

tion

Intensive care unit

stay

Pericardial

biopsy

Follow

up

(months) Outcome

1 ID 2004 8 days, LCOS, RF,

RDS

Non-specific

inflammation

4.04 Death from

pneumonia + sepsis

2

TB 2004 1 day, uneventful

Granulomatous

inflammation

95.0 NYHA class I

3 MG 2005 7 days, LCOS, RF,

RDS

Neoplastic

involvement

†

2.9 Death from disease

progression

4 MG 2005 2 days, uneventful

Neoplastic

involvement

‡

19.7 Death from disease

progression

5 TB 2006 8 days, re-operation

for bleeding, RF, RD

Granulomatous

inflammation

79.9 NYHA class III

6 ID 2006 6 days, re-operation

for bleeding, RF, RD

Non-specific

inflammation

25.7 Death from

advanced HF

7 MG 2007 2 days, uneventful

Neoplastic

involvement

§

25.6 Death from disease

progression

8 TB 2007 8 days, LCOS, RD Non-specific

inflammation

66.4 NYHA class II

9 ID 2007 1 day, uneventful

Non-specific

inflammation

62.5 NYHA class I

10 ID 2008 5 days, low-dose

inotrope

Non-specific

inflammation

51.3 NYHA class I

11 TB 2008 2 days, uneventful

Granulomatous

inflammation

48.2 NYHA class II

12 ID 2012 3 days, low-dose

inotrope

Non-specific

inflammation

8.9 NYHA class II

ID: idiopathic, TB: tuberculous, MG: malignancy, LCOS: low-cardiac output syndrome,

RF: renal failure, RD: respiratory distress, NYHA: NewYork Heart Association, HF: heart

failure.

†

Neoplastic cell invasion without definitive diagnosis,

‡

Pericardial involvement of malignant mesothelioma (epitolid type),

§

Pericardial involvement of high-grade diffuse B-type cell lymphoma.

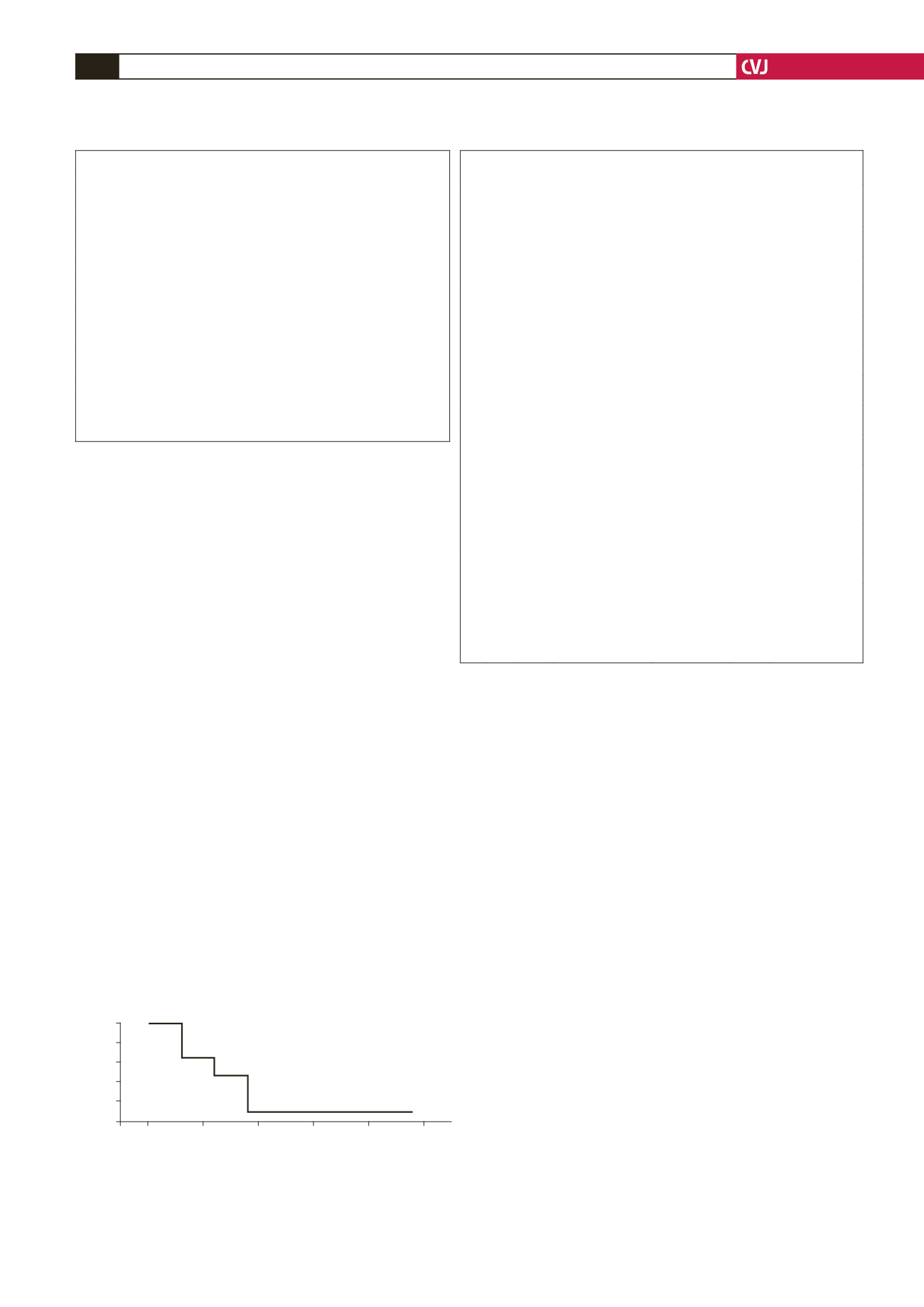

Fig. 1. Survival function of the entire group. The figure

displays the survival curve by lifetable analysis. The

overall mortality rate was 41.6%. Cumulative survival was

55.6

±

1.5% at the end of the two-year follow-up period.

1.0

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0

20

40

60

80

100

Cum survival

n

=

12

Time (months)