CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 8, September 2013

314

AFRICA

included pain, itching, limb heaviness, cramps, restless leg and

distress about cosmetic appearance. CEAP (Clinical, aEtiology,

Anatomical and Pathology) class was determined. All the

patients’ height and body weights were measured. The body

mass index was verified with the following formula: weight (kg)/

height

2

(m).

13

In all patients, the potential risks and benefits of endovenous

radiofrequency ablation therapy were explained, and written

informed consent was obtained. Additionally, throughout the

study the principles of the Helsinki Declaration were strictly

followed.

Doppler venous scanning was performed on all patients in

order to document the extent and severity of the reflux in the

great saphenous vein and to evaluate the deep venous system.

Doppler imaging of the patients was performed by Aloka

Prosound Alpha 7 (Hitachi Aloka Medical, Japan) using 5- and

7-mHz linear probes.

Reflux was determined at the saphenofemoral and

saphenopoliteal junctions in the standing position using the

Valsalva manoeuvre or manual distal compression with rapid

release. Pathological venous reflux was defined as a reverse flow

extending for 0.5 seconds or longer. The localisation and severity

of the venous reflux and sonographic distribution of the varicose

veins were recorded.

Other parameters measured using grey-scale ultrasound in the

standing position are as follows:

•

the diameter of the GSV in the SFJ

•

the diameter of the GSV above the knee

•

the distance of the GSV from the skin above the knee

•

the distance of the GSV from the skin in the middle of the

thigh

•

the length of the GSV that was to be ablated.

Only patients with documented GSV reflux with Doppler

ultrasonography and in CEAP class 2 or above were recruited

into the study. Patients were excluded if there was a significant

reflux in the deep venous system, small saphenous vein or

perforators. Other exclusion criteria included: deep-vein

thrombosis, superficial thrombophlebitis, peripheral arterial

vascular disease, immobility, pregnant or breast-feeding patients,

and previous history of allergy to local anaesthesia.

All cases in this study were performed under general

anaesthesia using a laryngeal mask combined with either

tumescent anaesthesia or a local hypothermia and compression

technique. Electrocardiogram, arterial pressure and oxygen

saturation of the patients were continously monitored. Induction

was achieved with midazolam (0.03 mg/kg), lidocain (1 mg/kg)

and propofol (2 mg/kg). Anaesthesia was maintained with 2%

sevoflurane.

Between January and December 2012 we treated 344 patients

in CEAP clinical class 2–6 with endovenous radiofrequency

ablation. These patients were divided into two groups according

to the anaesthetic management as follows. Group 1: 58 males,

114 females (

n

=

172). Tumescent anaesthesia was given

before the ablation procedure. Group 2: 42 males, 130 females

(

n

=

172). The procedure was performed without tumescent

anaesthesia. Local hypothermia and compression technique was

used.

Patients were placed in the supine position. Prior to

performing RFA, Doppler ultrasonography was used to confirm

the important parameters, including imaging of the GSV and

SFJ, perforators, tributaries, and diameter and treatment length,

to devise an effective operative plan.

A linear 5- or 7-MHz probe was inserted into a sterile cover

and using ultrasound guidance, the GSV was cannulated below

or just above the knee. Following the introduction of a 0.025-

inch guidewire into the GSV, a 4- or 5-Fr intraducer sheath was

advanced over it. The RFA catheter (ClosureFast radiofrequency

ablation catheter, NYSE:COV) was then placed through the

sheath, the guidewire was removed and the tip of the catheter

was placed 2–3 cm distal to the SFJ, just below the superficial

epigastric vein, under ultrasound guidance.

Once proper positioning was confirmed with ultrasound,

a tumescent anaesthetic solution was instilled percutaneously

below the saphenous fascia to surround the vein in group

1 patients. This solution consisted of 500 ml saline, 20 ml

2% prilocaine, 20 ml 8.4% sodium bicarbonate and 0.5 ml

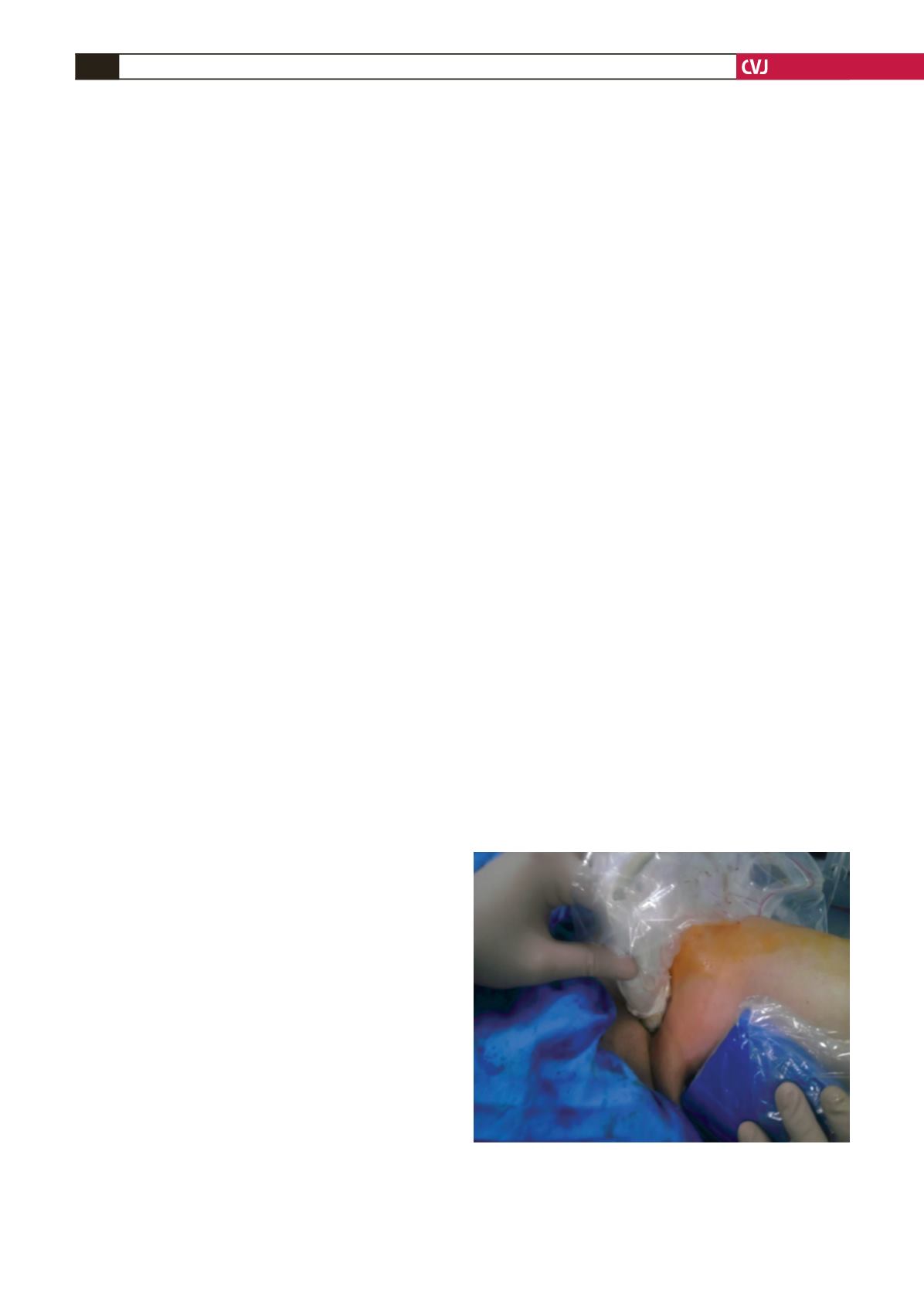

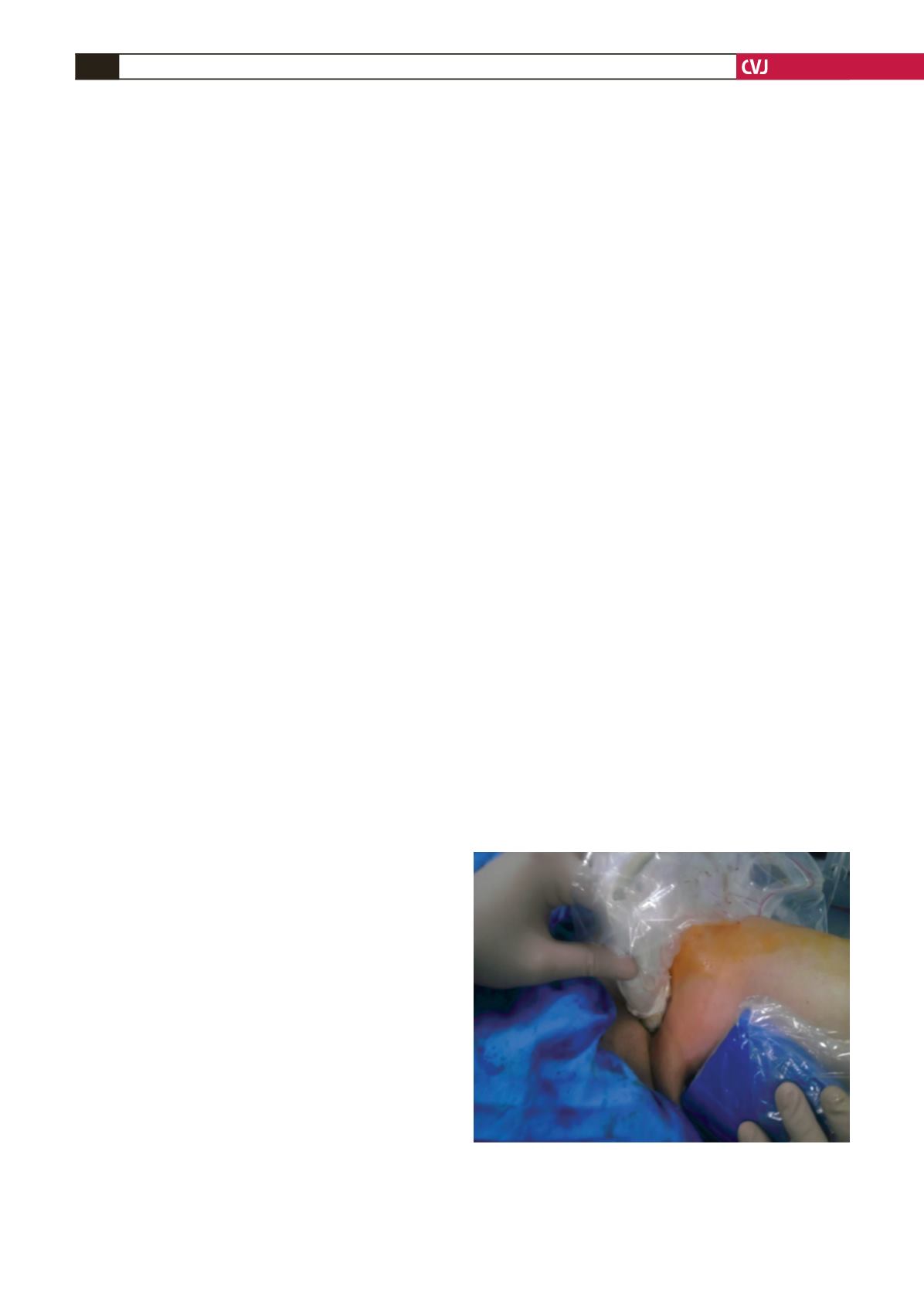

epinephrine. In group 2, instead of local tumescent anaesthesia,

we used a local hypothermia technique (external compression

with ice and dampening the skin with saline (+4°C) in order to

prevent skin burn) (Fig. 1).

The RF generator (VNUS Medical Technologies) was then

activated and delivery of radiofrequency energy was maintained

at 120°C. Radiofrequency ablation was performed at a rate of

40 W per 7 cm. During the procedure, in both groups, sufficient

pressure was exerted with the ultrasound probe to occlude the

SFJ and CFV. Following completion of the procedure, closure

of the GSV and patency of the common femoral vein and

superficial epigastric vein was checked with Doppler ultrasound.

As the last step of the treatment, all varicose veins were removed

by phlebectomy in both groups (Figs 2, 3).

A compression bandage was wrapped around the treated

limb and the patient was encouraged to walk immediately. This

remained in place for three hours. The patients wore class II

(30–40 mmHg) thigh-high compression stocking continously for

the next 24 hours. They then wore the compression stocking only

during the day for the next 15 days. The patients were prescribed

a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, an antibiotic and a veno-

active drug during the postoperative period.

Fig. 1. Local hypothermia and compression technique:

external compression with Doppler probe for preventing

extension of the thrombus to the deep venous system,

and external compression with ice and dampening of the

skin with saline (+4°C) in order to prevent skin burn.