CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 25, No 3, May/June 2014

112

AFRICA

peripheral neuropathy].

10

Continuous hyperglycaemia may cause

endothelial dysfunction and vascular lesions, resulting in diabetic

vascular complications.

11,12

Type 2 diabetes is a substantial risk factor in atherosclerotic

cardiovascular disease.

13,14

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the

leading cause of death in patients with type 2DM.

15

Asymptomatic

CAD is common in patients with DM and is a strong predictor

of future poor outcome of coronary vascular events, as well as

early death.

16,17

DM is associated with generalised endothelial

dysfunction and small-vessel abnormalities.

18,19

Perfusion defects are substantial predictors of coronary

events in patients with known or suspected coronary heart

disease (CHD).

20

It is proposed that concomitant abnormalities

of perfusion imaging scans in patients with diabetes with normal

coronary angiograms may be caused by micro-angiopathy or

endothelial dysfunction. Accordingly, it reflects an increased

likelihood of future coronary events.

21

The majority of studies on ischaemia have used SPECT MPI.

An analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of pharmacologically

induced stress MPI reported a mean sensitivity and specificity

of 88 and 77%, respectively.

22

Platelet volume is a marker of platelet activation and function,

and is measured usingMPV.

5

Platelets that have dense granules are

more active biochemically, functionally and metabolically. Large

platelets secrete high levels of prothrombogenic thromboxaneA2,

serotonin, beta-thromboglobulin and procoagulant membrane

proteins such as P-selectin and glycoprotein IIIa.

5,23

Platelets

secrete a large number of substances that are crucial mediators

of coagulation, inflammation, thrombosis and atherosclerosis.

24,25

It is also well known that large platelets are a risk factor

for developing coronary thrombosis, leading to myocardial

infarction.

19,23,26,27

Measurement of platelet activation and/or aggregation may

provide prognostic information in patients at risk for or following

a cardiovascular event.

28,29

Reports have revealed that there is a

close relationship between MPV and cardiovascular risk factors,

including impaired fasting glucose levels, diabetes mellitus,

hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, obesity and the metabolic

syndrome.

30-32

Increased platelet activity is reported to play a

role in the development of vascular complications in diabetic

patients.

18

MPV was increased in patients with SCF complex and cardiac

syndrome X, both being related to microvascular defects and

endothelial dysfunction.

33,34

In the present study, we showed that

MPV was associated with myocardial perfusion defect, using

MPI in diabetic patients.

In our study, MPV was increased in the myocardial perfusion

defect group compared to those without myocardial perfusion

defects. DM not only involves the main coronary artery but also

the microvascular circulation, leading to myocardial perfusion

defects. Perfusion defects are significant predictors of coronary

events in patients with known or suspected CHD.

20

The main limitation of our study was the small sample size,

which could result in low statistical power for equivalency

testing, leading to false-negative results. Second, because of the

retrospective nature of data collection, the angiographic results

of the patients were not evaluated. MPI may reflect myocardial

perfusion defects but it was not able to show the anatomical

status of the coronary artery. We cannot extend our results to the

general population due to our broad exclusion criteria.

Conclusion

MPV levels were higher in the diabetic patients with myocardial

perfusion defects than in those without myocardial perfusion

defects. In diabetic patients, increased MPV may be an

independent marker of myocardial perfusion defects, which are

associated with adverse coronary events.

References

1.

Whiteley L, Padmanabhan S, Hole D, Isles C. Should diabetes be

considered a coronary heart disease risk equivalent? results from 25

years of follow-up in the Renfrew and Paisley survey.

Diabetes Care

2005;

28

: 1588–1593.

2.

Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The

Framingham study.

J Am Med Assoc

1979;

241

: 2035–2038.

3.

Nathan DM, Meigs J, Singer DE. The epidemiology of cardiovascular

disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: how sweet it is ... or is it?

Lancet

1997;

350

(Suppl 1): SI4–9.

4.

Misko J. Evaluation of myocardial perfusion and viability in coronary

artery disease in view of the new revascularization guidelines.

Nuclear

Med Rev Central Eastern Eur

2012;

15

: 46–51.

5.

Martin JF, Shaw T, Heggie J, Penington DG. Measurement of the densi-

ty of human platelets and its relationship to volume.

Br J Haematol

1983;

54

: 337–352.

6.

Erhart S, Beer JH, Reinhart WH. Influence of aspirin on platelet count

and volume in humans.

Acta Haematol

1999;

101

: 140–144.

7.

Zuberi BF, Akhtar N, Afsar S. Comparison of mean platelet volume

in patients with diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose and non-

diabetic subjects. S

ingapore Med J

2008;

49

: 114–116.

8.

Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V,

et al

. Standardized myocar-

dial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of

the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac

Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the

American Heart Association.

Circulation

2002;

105

: 539–542.

9.

Ficaro EP, Lee BC, Kritzman JN, Corbett JR. Corridor4DM: the

Michigan method for quantitative nuclear cardiology.

J Nucl Cardiol

2007;

14

: 455–465.

10. Murea M, Ma L, Freedman BI. Genetic and environmental factors

associated with type 2 diabetes and diabetic vascular complications.

Rev Diabet Studies

2012;

9

: 6–22.

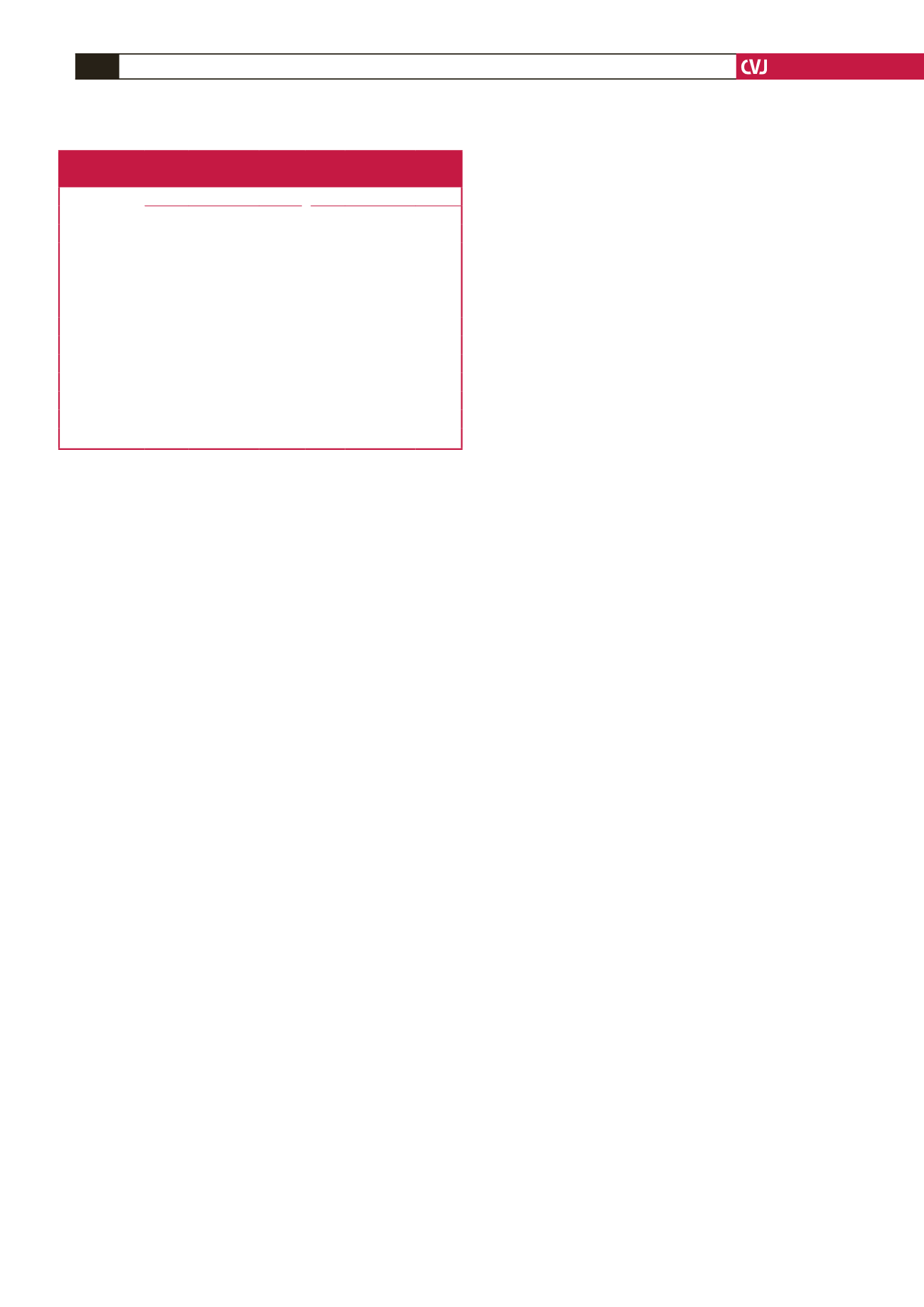

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses of

independent variables for MPD.

Univariate

Multivariate

Variables

OR 95% CI

p

-value OR

95% CI

p

-value

MPV (fl)

2.401 1.298–4.440 0.005 2.484 1.215–5.081 0.013

Glucose (mg/dl) 1.009 0.999–1.029 0.072 1.008 0.997–1.019 0.178

HbA

1c

(%)

1.800 0.993–3.474 0.08 1.984 0.980–4.018 0.064

Age (years)

1.011 0.963–1.061 0.664

Gender

1.244 0.497–3.16 0.641

HT (mg/dl)

2.375 0.801–7.043 0.119

BMI (km/m

2

)

0.991 0.92–1.067 0.820

TC (mg/dl)

0.994 0.984–1.004 0.256

TG (mg/dl)

0.998 0.994–1.002 0.360

HDL-C (mg/dl) 0.948 0.878–1.023 0.167

LDL (mg/dl)

0.989 0.975–1.003 0.134

Hb (%)

1.138 0.845–1.534 0.395