CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 27, No 3, May/June 2016

AFRICA

189

Keywords:

cardiology training in South Africa, cardiothoracic

surgery training in South Africa

Submitted 3/2/16, accepted 18/5/16

Cardiovasc J Afr

2016;

27

: 188–193

www.cvja.co.zaDOI: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-063

Why is it important to train specialists in cardio-

vascular care and heart health in South Africa?

The Global Burden of Disease study has highlighted that South

Africa has an unacceptably high proportion of premature

mortality

1

and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost from

cardiovascular disease. This is largely in part due to marked

increases in hypertensive, rheumatic as well as ischaemic heart

disease, and heart failure due to cardiomyopathy from 1990–

2010.

2

Rapid demographic changes and adaptation to the

so-called Western lifestyle, which includes low physical activity

and high intake of processed high-caloric food, has led to more

than one-third of the population being obese and hypertensive.

3

In South Africa and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the spectrum

and manifestation of cardiovascular disease is complex and

markedly different compared to high-income countries, as

rheumatic heart disease (RHD), tuberculous pericarditis and

the cardiomyopathies remain common and often present at an

advanced stage due to cardiac failure.

4

Furthermore, over half

of the patients hospitalised with heart failure are under 52 years

of age.

5

Patients with myocardial infarction are typically two

decades younger than patients in the USA and Europe

6

(Table

1), and RHD becomes symptomatic in adulthood. The onset of

serious heart disease before the sixth decade of life has important

economic and other implications for South African society.

7

A study from the Heart of Soweto cohort, reporting on the

incidence and clinical characteristics of newly diagnosed RHD

in adulthood from an urban African community, found an

estimated incidence of new cases of RHD for those over 14 years

of age to be in the region of 23.5 cases/100 000 per annum.

8

Due

to undetected RHD in the early years, many of those patients

presented late, with left or right heart failure. Subsequently,

one-quarter of this cohort of 344 cases needed valve replacement

or repair within one year, with a further 26% being admitted for

initial diagnosis of suspected bacterial endocarditis within 30

months.

The severity of disease was further corroborated in a recent

study from 12 African countries, including South Africa, India

and Yemen. Patients with RHD were young (median age 28

years), largely female and mostly severely affected.

9

A further

burden of late diagnosis of RHD is the fact that women often

present with symptomatic RHD only when pregnant. A four-

year audit of cardiac disease in pregnancy in a South African

hospital found an aetiology of 63.5% of RHD and 20.1% of

prosthetic valvular heart disease (probably of RHD origin)

among these women.

10

A recent single-centre cohort study of 225 consecutive

women presenting with cardiac disease in pregnancy at a

dedicated cardiac disease in maternity clinic at Groote Schuur

Hospital, Cape Town, highlighted the complex burden of

symptomatic RHD (26%), congenital heart disease (32%) and

severe cardiomyopathy (27%), among other cardiac conditions.

11

Mortality occurred typically in the postpartum period beyond the

standard date of recording maternal death, as also highlighted in

a recent publication in the

Lancet

.

12

The confidential inquiry

into maternal deaths in South Africa reported that, of the 4 867

deaths reported over two years, 14% were due to hypertensive

disorders, with another 8.8% due to medical and surgical

conditions.

13

Medical disorders, in particular cardiac disease

complicating pregnancy, were the fourth most common cause of

maternal death during pregnancy.

Howwell is SouthAfrica prepared to transformour healthcare

system to meet the demands of two colliding and interacting

epidemics: a communicable disease epidemic of HIV/AIDS

and tuberculosis, and a rapidly expanding second epidemic of

non-communicable cardiovascular diseases?

Training of doctors and healthcare personnel

in South Africa

Between 2000 and 2012, the number of medical students

enrolling per annum increased by 34%, with a major and

deliberate demographic shift towards more female students

and African blacks.

14,15

Subsequently, the number of graduating

doctors has increased by 18% in the same time period. However,

the ratio of physicians per 1 000 population remained the same

(0.77 in 2004 vs 0.76 in 2011) and is failing to keep up with the

growth of the population.

15

In response to the fact that the academic health workforce

in South Africa is aging, numbers are shrinking, and there is a

decline in clinical research capacity and output, two new research

training tracks within the professional MB ChB programme have

been created. These are the intercalated BSc (Med) Hons/MB

ChB track and the integratedMB ChB/PhD track.

16

Furthermore,

the Ministry of Health has pledged to train 1 000 clinician PhDs

though the National Health Scholars Programme over the next 10

years, providing scholarships equivalent to the salaries of health

professionals employed by the Department of Health.

16

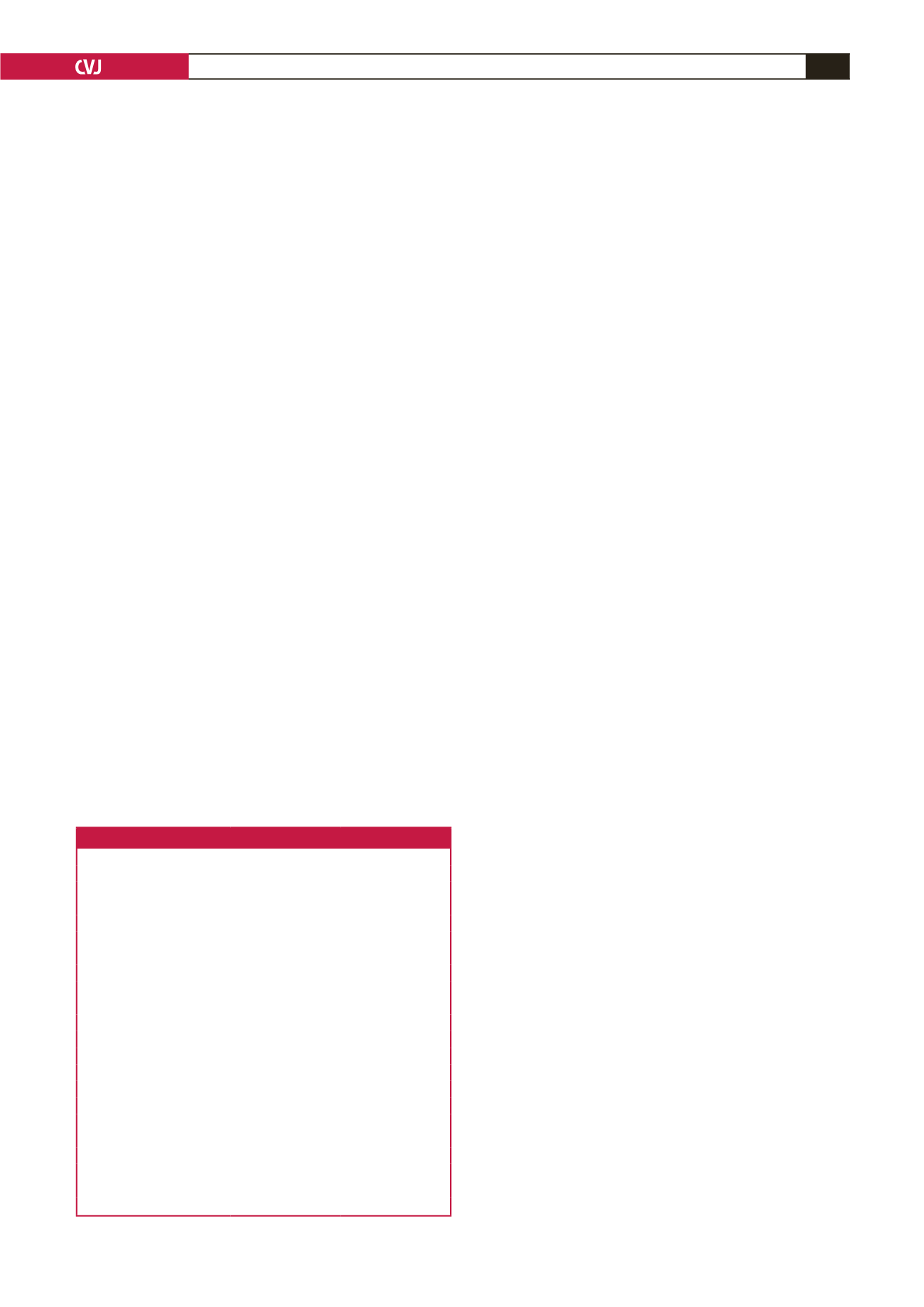

Table 1. Comparison of age at first myocardial infarction

Region

Medium age, women Medium age, men

Western Europe

68

61

Central and Eastern Europe

68

59

North America

64

58

South America and Mexico

65

69

Australia and New Zealand

66

58

Middle East

57

50

South Asia

60

52

Africa

56

52

China

67

60

South-east Asia and Japan

63

55

Ethnic origin

European

68

59

Chinese

67

60

South Asian

60

50

Other Asian

63

55

Arab

57

52

Latin American

64

58

Black African

54

52

Coloured African

58

52

Other

63

53

Overall

65

56