CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 1, January/February 2017

AFRICA

61

is mostly caused by hypertension and not by coronary artery

disease, as is seen in Western countries.

4

Patients with HF are heterogeneous in terms of risk of

cardiac death and re-admission for decompensated HF. Therefore

assessment of prognosis is a fundamental step in individual patient

management. Analysis of clinical variables has helped in identifying

the most significant predictors of mortality in the HF population.

5

Echocardiography has become the gold standard for the

evaluation of patients with HF because it is an inexpensive,

highly reproducible, widely available and relatively extensive

method for assessing left ventricular systolic and diastolic

function.

6

In fact, the recent HF guidelines of the European

Society of Cardiology state that ‘echocardiography is the method

of choice in patients with suspected HF for reasons of accuracy,

availability (including portability), safety, and cost’.

7

More than 20 echocardiographic parameters have been

proposed as predictors of outcome in HF patients in a number

of clinical studies.

8

However, the role of echocardiography in

the assessment and risk stratification of acute HF has been less

clear. Some small studies have found little correlation between

echocardiographic and haemodynamic variables in acute HF,

and little change in these variables from admission to follow

up.

9

In large registries and trials, echocardiographic parameters

were not found in many cases to be associated with outcomes.

10

Therefore, it is not clear which echocardiographic variables are

of importance in patients with acute HF.

5,11

THESUS-HF

3

provided a unique opportunity to study the

echocardiographic predictors of outcome in patients admitted with

acute HF in this part of the world. To our knowledge, no similar

study has been previously published in Africans with acute HF.

Methods

THESUS-HF was a prospective, multicentre, international

observational survey of acute HF in 12 cardiology centres from

nine countries in sub-SaharanAfrica.

3

All participating centres had

a physician trained in clinical cardiology and echocardiography.

Patients who were older than 12 years, were admitted with

dyspnoea as the main complaint, and were diagnosed with

acute HF based on symptoms and signs that were confirmed

by echocardiography (

de novo

or decompensation of previously

diagnosed HF) were enrolled consecutively. Patients excluded

were those with acute coronary syndromes, severe known renal

failure (patients undergoing dialysis or with a creatinine level of

>

4 mg/dl), nephrotic syndrome, hepatic failure or other cause of

hypoalbuminaemia.

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject

who was enrolled into the study. Ethical approval was obtained

from the ethics review boards of the participating institutions,

and the study conformed to the principles outlined in the

Declaration of Helsinki.

Details of data collection have been previously described.

3

In

brief, we collected demographic data, detailed medical history,

vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and

temperature) and signs and symptoms of heart failure (oxygen

saturation, intensity of oedema and rales, body weight and levels

of orthopnoea). Assessments were done at admission and on

days 1, 2 and 7 (or at discharge if earlier).

Electrocardiograms were done and read using standard

reference ranges. A detailed echocardiographic assessment was

performed (see below). The probable primary cause of HF was

provided by the investigators, and was based on the European

Society of Cardiology guidelines,

7

as recently applied in the

chronic HF cohort of the Heart of Soweto Study.

12

Information

on re-admissions and death, with respective reasons and cause,

was collected throughout the six-month follow up. Outcomes of

interest were re-admission or death within 60 days, and death up

to 180 days.

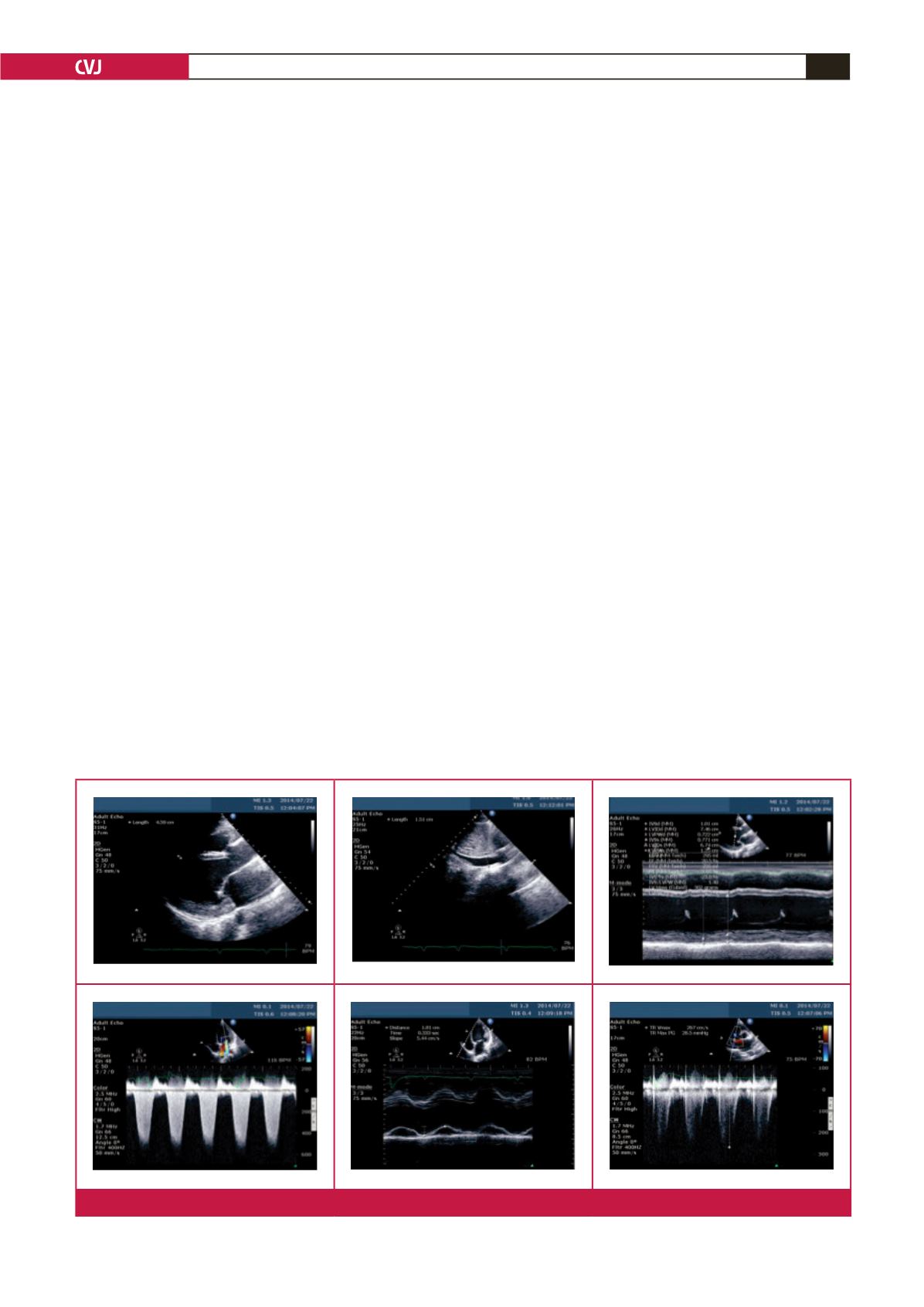

Fig. 1.

Echocardiography images depicting method of echo assessment in the study.