CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 4, July/August 2018

250

AFRICA

laboratory, while the other was referred for surgery where the

PDA was ligated and the embolised device was removed.

Discussion

This study shows that transcatheter occlusion of PDAs is safe

and effective in our setting. In particular, the introduction of the

Amplatzer™ devices raised the safety and effectiveness of closure

and a wider spectrum of PDAs can now be closed at the facility.

The need for surgical intervention has declined markedly. Reducing

the number of these cases by using percutaneous closure of PDAs

decreases the time patients with other congenital heart diseases

spend waiting for surgery. The data presented for the period 2008–

2017 showed the predominance of Amplatzer devices continued

and that few complications occurred with these procedures.

The predominance of females in our study is notable and

consistent with what is commonly found in isolated PDAs.

17

Interestingly, in contrast with Krichenko’s description of PDA

shapes, where type B was the second commonest,

1

this shape was

the least common in our population.

The findings of our study add to reports from other settings.

In 2006, Galal

et al

. summarised evidence on PDA occlusion

from 1995 to 2004, covering 21 articles, which included almost

2 800 patients.

6

Our early closure rates are lower than those

reported in that review, although definitions of early closure

differ between our study and the review (Fig. 5). Late closure

rates in our population, however, approximate their reported

range. Late occlusion is perhaps the most important outcome

measure, as it is a key determinant of whether further procedures

are required and of the patient’s risk of endocarditis.

18

The rate

of device embolisation during our study period was acceptable,

falling between the highest and lowest rates reported in the review.

In 2004, Pass published a multicentre review of closure of

PDAs with the Amplatzer™ duct occluder, covering 484 patients

from 25 centres.

19

Our results are very similar to those of the

review, with early closure rates around 90% in the review and in

our study. Total closure rates of 97% in our study were almost

identical to the 98% in that review. The characteristics of our

population and that of the Pass review are similar (e.g. age and

weight), as are the PDA sizes and shunt ratios.

While the above studies were done mostly in high-income

countries, use of these devices has also been assessed in other

middle-income countries.

4,5

A study in Bloemfontein confirmed

the effectiveness of coils in 36 patients in a southern African

environment.

14

Notably, our fluoroscopy time was considerably longer than

all the results reported by Galal

et al

.

6

There are multiple

reasons likely account for this finding. Firstly, we perform a

full diagnostic catheterisation prior to closing the PDA, while

in other settings a briefer catheterisation may have been done,

focused on only closing the duct. Secondly, the introduction of

a new device (Amplatzer) necessitated a considerable learning

curve for the catheterisation team, prolonging the procedure

for the initial patients. The slight increase in number of patients

requiring a repeat procedure to close a PDA around the time that

the Amplatzer devices were introduced was also likely due to the

learning curve.

Finally, our facility is a nationally accredited paediatric

cardiac training centre, with a high turnover of trainees who

each need to perform several procedures in order to become

proficient, and to complete their sub-speciality. As a result, these

procedures most often involve close supervision and teaching of

trainees with little or no experience. The long fluoroscopy time is

an important finding, and results in increased radiation exposure

to both patients and staff. Clearly, attention needs to be paid to

strategies to reduce radiation exposure in our setting.

Study limitations

Types of procedures and outcomes of current care may differ

from that of our study, given that our data collection ended

in 2008 and new devices have been introduced since then.

Nevertheless, these data describe the important transitions in our

unit from one type of device, coils, to the Amplatzer range, and

from surgery to transcatheter closure. Furthermore, this study

is limited in that it is a retrospective record review. While efforts

were made to capture all available data, some information was

missing. Similarly, most patients who underwent surgery prior to

the era of device closure did not undergo cardiac catheterisation

so the data relating to PDA size and shape were not available for

these patients, limiting our ability to compare these and other

patients.

Conclusions

Transcatheter closure of PDAs in the catheterisation laboratory

at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital is both safe and

effective. The treatment outcomes are similar to those in high-

income countries, which have considerably more resources for

treating their patient populations. The introduction of a new

device, although associated with a learning curve, broadened the

range of PDAs that could be closed and improved closure rates.

Efforts are needed to address the factors influencing fluoroscopy

times. As more devices become available, the range of PDAs that

could be closed will likely further increase.

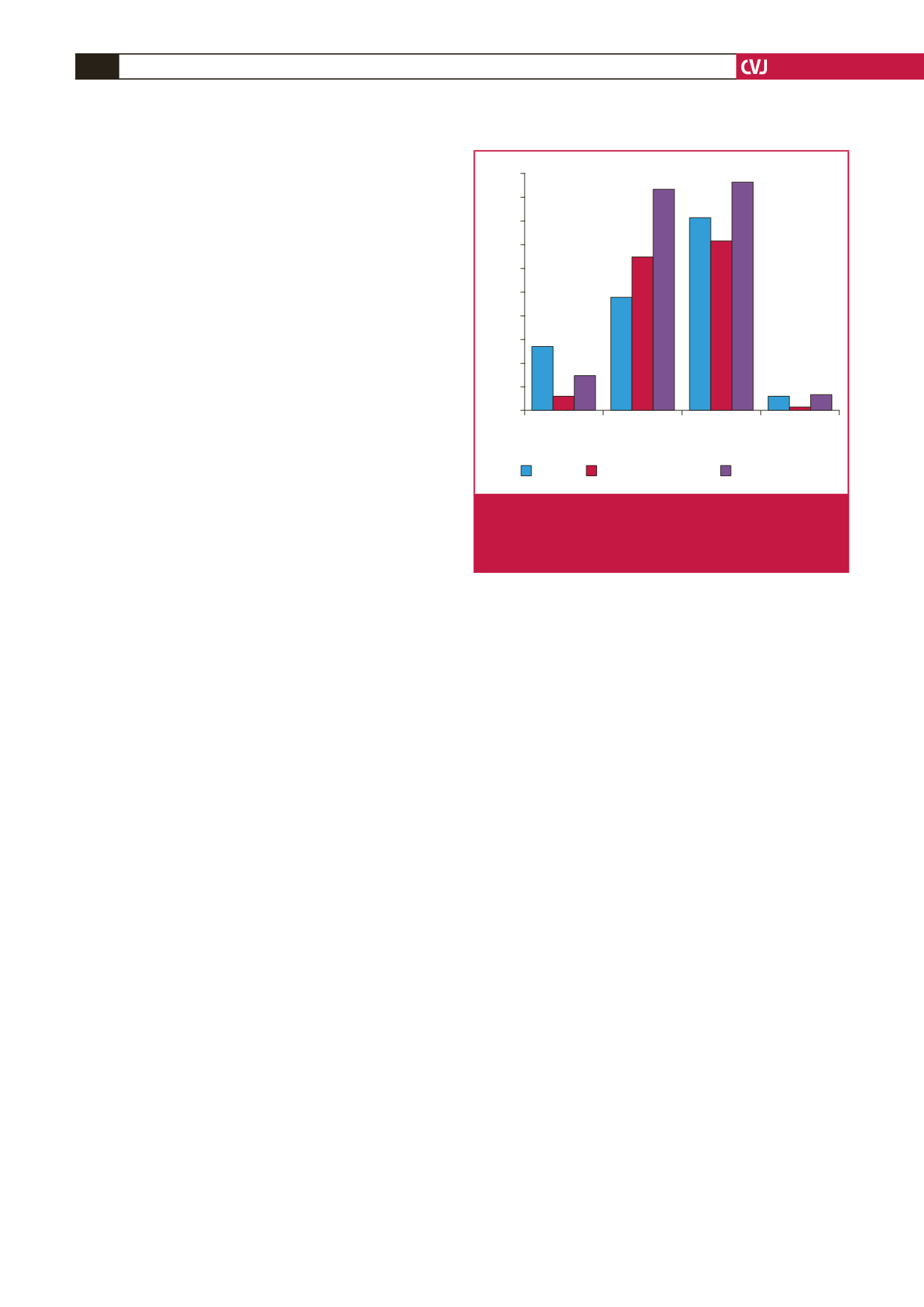

CHBH Galal

et al.

– lowest

Galal

et al.

– highest

Fluoroscopy

time (mins)

Early

occlusion (%)

Late

occlusion (%)

Embolisation

(%)

PDA closures

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Fig. 5.

Comparison of PDA closure with coils between our

results and the review reported by Galal

et al

.

6

(lowest

refers to lowest values in studies reviewed, and high-

est refers to highest values in studies reviewed).