CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 32, No 3, May/June 2021

AFRICA

131

surgery was performed. One of the two patients with LMCA

lesions could not be saved and died. The other three patients

underwent successful CABG operations and were discharged

from the hospital.

Discussion

CEA has been shown to reduce the risk of stroke in both

asymptomatic and symptomatic patients in several large

trials.

3,4,9,10

Current European Society for Vascular Surgery

guidelines identify five different indications in patients with

carotid artery disease, including neurological symptomatology,

degree of carotid stenosis, medical co-morbidities, vascular

and local anatomical features and carotid plaque morphology.

The last three of these criteria were proposed as a means

of differentiating between CEA and carotid artery stenting

(CAS).

11

However, in terms of stroke and death, numerous

randomised trials did not find any significant difference between

CEA and CAS. Stenting may have some possible advantages,

such as avoidance of GA and surgical trauma,

12-14

although it

has also been identified as an independent predictor of retinal

embolisation.

15

In the 1960s, with the initiation of operations under LA,

many surgeons began to prefer it when performing operations.

16

In our clinic, many of the surgeons also prefer LA, resulting

in more CEA operations being performed under LA. Previous

studies have suggested that use of LA for CEA surgery may

change the attitude of many surgeons to the procedure.

17,18

Since

it alerts the surgeon for the necessity of a shunt, awake testing

of brain function during carotid clamping under LA is more

reliable than various indirect techniques that are used under

GA. Such an approach may be safer than operations performed

under GA, as evidenced by the lower number of shunts used in

these procedures. In our study, shunts were used less frequently

in patients who underwent CEA under CB anaesthesia; however,

this difference was not statistically significant.

Awake testing and cerebral monitoring are regarded as the

gold standard for shunting.

19

Although shunts should protect

the brain from strokes caused by low cerebral blood flow during

carotid clamping, they can damage the arterial wall, causing

embolisms in the brain.

LAmay have some advantages in terms of MI and pulmonary

complication rates, when compared with GA.

17

Furthermore,

LA is associated with a better assessment of neurological

outcomes.

20,21

The GALA study included 3 526 patients and

compared GA versus LA for carotid artery surgery. It found no

significant differences in quality of life, length of hospital stay,

or primary outcome (stroke, MI, death between randomisation

and 30 days after surgery) in the pre-specified subgroups of

age (above or below 75 years) or for those considered at higher

risk for surgery. While the study provided important insights

into disease outcomes based on treatment modalities, it did

not answer questions regarding the safety of CEA under LA in

patients at high risk for cardiovascular complications.

Conclusion

In our study, the postoperative MI rate was higher in the

CB-GA group, with four cases of postoperative MI in the

CB-GA group compared to none in the GA group. Based on

these observations, for patients requiring CEA and CABG,

performing both operations under GA and in the same session

was the safer option compared to initially performing CEA

under CB anaesthesia followed by CABG under GA.

References

1.

Eastcott HHG, Pickering GW, Robb CG. Reconstruction of internal

carotid artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia.

Lancet

1954;

2

: 994–996.

2.

DeBakey ME. Successful carotid endarterectomy for cerebrovascular

insufficiency. Nineteen-year follow-up.

J Am Med Assoc

1975:

233

;

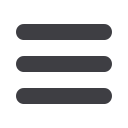

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and

clinical variables of the patient population

Variables

GA group

(

n

= 18)

CB-GA group

(

n

= 16)

p

-value

Age

66.39 ± 8.64

67.44 ± 6.34

0.692

Male

14 (77.8)

12 (75.0)

0.999

Asymptomatic

15 (83.3)

13 (81.2)

0.999

Amaurosis fugax

–

–

–

TIA

3 (16.7)

2 (12.5)

0.999

Non-disabling stroke

–

–

–

Stroke

0 (0.0)

1 (6.2)

0.471

Smoking

9 (50.0)

7 (43.8)

0.716

HT

2 (11.1)

7 (43.8)

0.052

DM

2 (11.1)

4 (25.0)

0.387

Hypercholesterolaemia

1 (5.6)

2 (12.5)

0.591

CAD

13 (72.2)

11 (68.8)

0.999

PAD

0 (0.0)

2 (12.5)

0.214

Renal dysfunction

4 (22.2)

2 (12.5)

0.660

Obesity

2 (11.1)

2 (12.5)

0.999

GA: general anaesthesia; CB: cervical block; TIA: transient ischaemic attack;

HT: hypertension; DM: diabetes mellitus; CAD: coronary artery disease; PAD:

peripheral arterial disease.

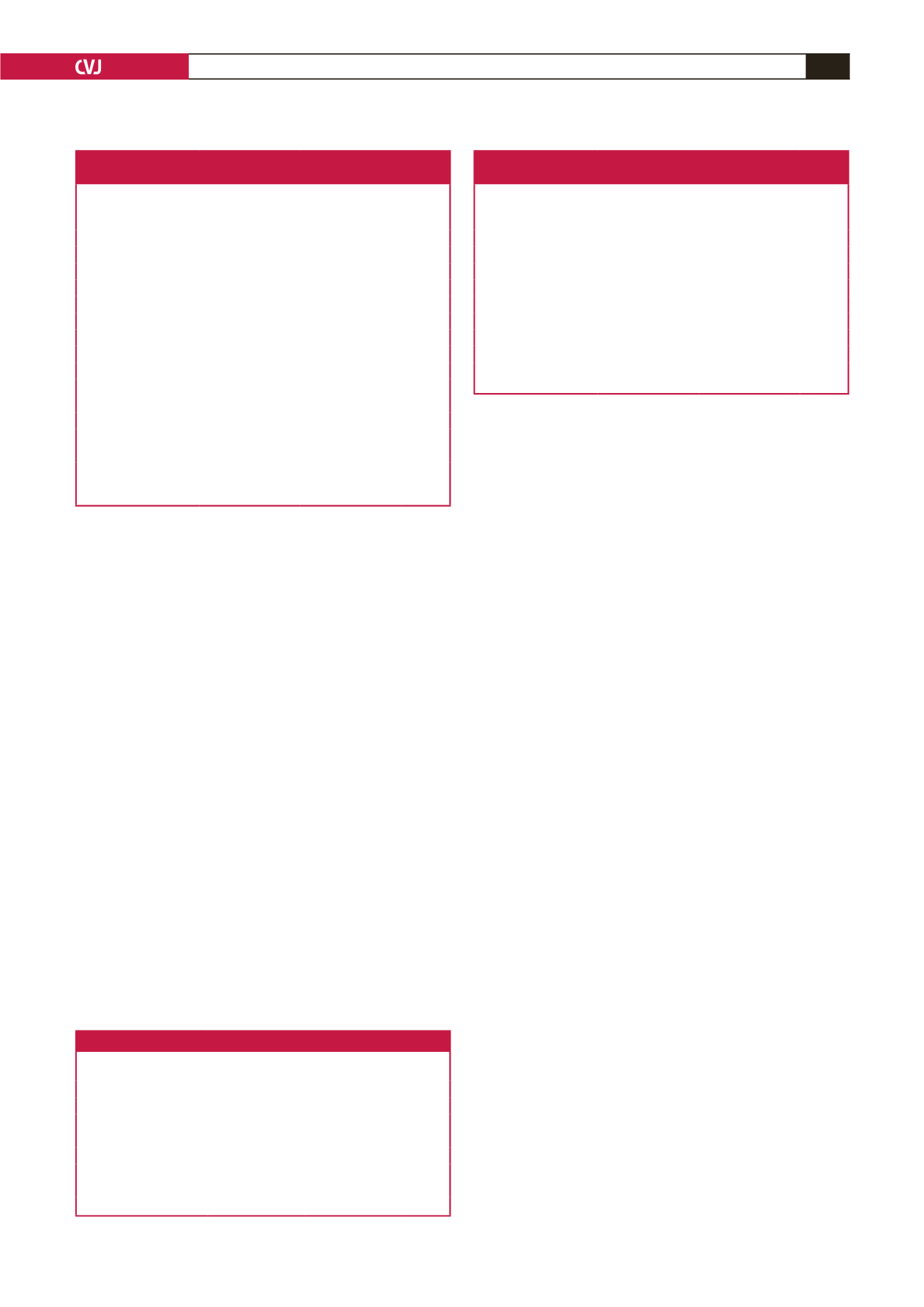

Table 2. Intra-operative data of the patient groups

Variables

GA group

(n = 18)

CB-GA group

(n = 16)

p

-value

Clamping time

31.06 ± 3.57

41.25 ± 7.39 < 0.001

Contralateral obstruction

2 (11.1)

3 (18.8)

0.648

Shunt

2 (11.1)

3 (18.8)

0.648

Primer closure

6 (33.3)

4 (25.0)

0.715

Saphenous

0 (0.0)

1 (6.2)

0.471

PTFE

–

–

–

Dacron

12 (66.7)

11 (68.8)

0.897

GA: general anaesthetic; CB: central block; PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene.

Table 3. Comparison of postoperative

complications between patient groups

Complications

GA group

(

n

= 18)

CB-GA group

(

n

= 16)

p-value

Bleeding

4 (22.2)

0 (0.0)

0.105

Infection

–

–

–

Cranial nerve damage

1 (5.6)

0 (0.0)

0.999

Early restenosis

–

–

–

Late restenosis

–

–

–

TIA

–

–

–

Stroke

–

–

–

Postoperative MI

0 (0.0)

4 (25.0)

0.039

Death

0 (0.0)

1 (6.2)

0.471

GA: general anaesthetic; CB: central block; TIA: transient ischaemic attack,

MI: myocardial infarction.