CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 4, May 2013

AFRICA

143

used for cardiopulmonary bypass, antibiotics and catheters used

for interventional treatment are still very expensive and almost

out of reach of the poorer countries.

Table 3 gives some representative costs in Africa, India and

the United States. The International Children’s Heart Foundation

sends teams to underdeveloped countries, and cites $2 500 for

the cost of open-heart surgery; this is almost certainly subsidised.

There are additional costs to congenital heart disease beyond

surgical treatment: medical treatment, cost of transport to

hospital, which is often difficult in rural Africa andAsia, and loss

of parental working time when they have to take the children to

a medical centre.

6

These costs are disproportionately severe in

countries with low incomes per capita.

In addition, both treated and untreated children with congenital

heart disease are at risk of infective endocarditis. This risk may

differ from country to country but we do not have good data.

One current estimate by Knirsch and Nadal

7

assessed the risk

of congenital heart disease as 1.5 to six episodes per year per

100 000 adults, and 0.34–0.64 episodes per year per 100 000

children.

Infective endocarditis produces considerable morbidity,

involves lengthy and costly treatment, and severely affects

longevity.Afollow-up study of patientswith infective endocarditis

and a variety of underlying heart diseases showed that fewer than

50% survived more than 20 years after the infection.

8

Finally, children with congenital heart disease have more than

heart disease to contend with. There can be associated defects in

several other organ systems, and neurodevelopmental problems

are particularly burdensome. Marino

et

al

.

9

reported in an

American Heart Association scientific statement that moderate

to severe neurodevelopmental disabilities occurred in over 50%

of children with severe congenital heart disease or congenital

heart disease palliated as neonates, and in 25% of those with less

severe anomalies.

Resources

The resources to treat congenital heart disease are both inadequate

and seriously maldistributed.

10-12

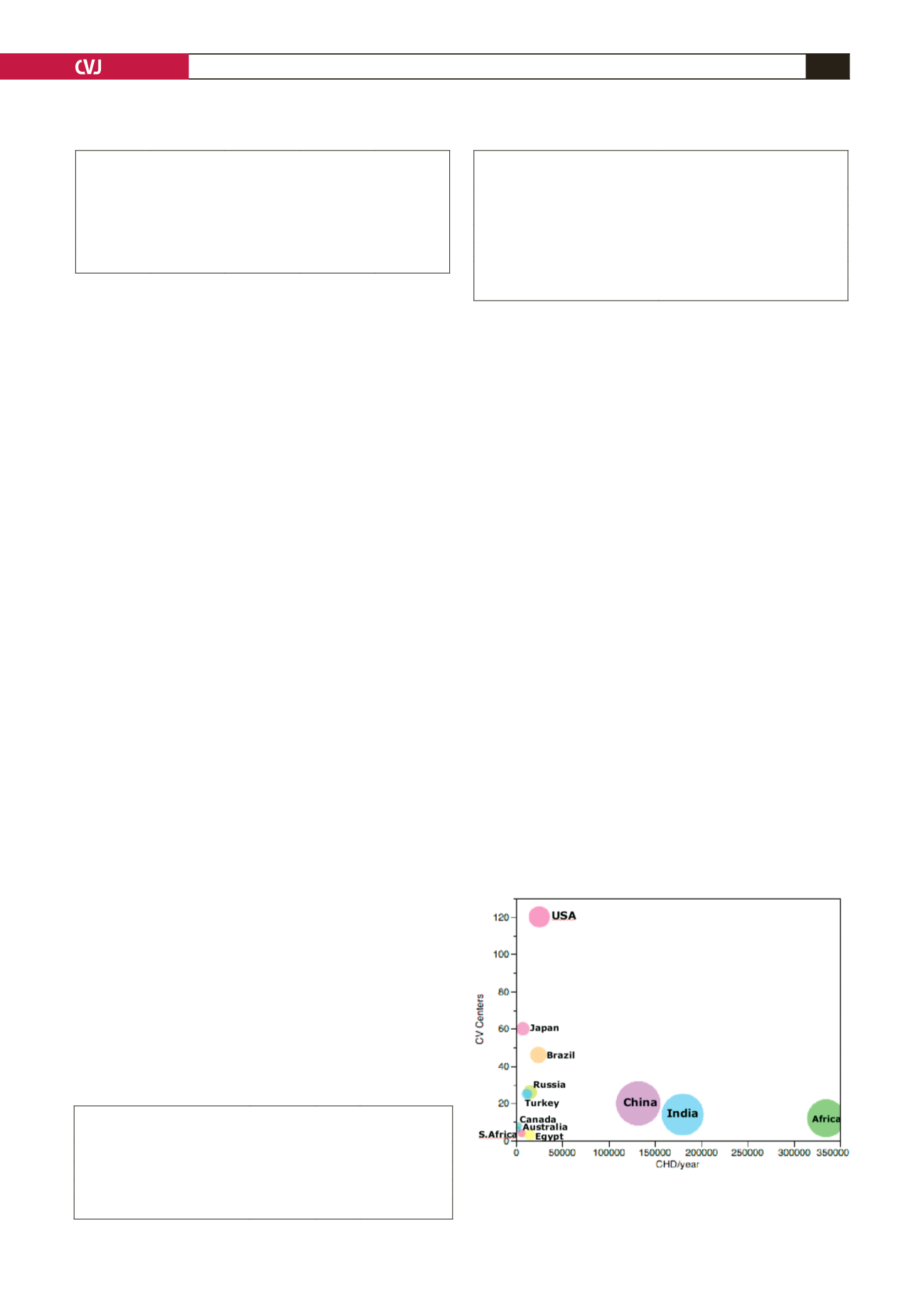

The 2007–2009 World Society

for Paediatric Heart Surgery Manpower Survey

11

noted that about

75% of the world’s population have no access to cardiac surgery,

and that the distribution of cardiac surgeons was very unbalanced

(Table 4). This is in keeping with the variation in distribution of

cardiovascular centres (Fig. 6).

Prospects and potential solutions

The issues are so complex that it is difficult to know where to

begin. Poverty, the greatest barrier to successful treatment of

congenital heart disease, has multiple causes that are complex

and difficult to remove. Natural resources may be inadequate

or, where resources (oil, diamonds, ores) exist, corrupt and

inefficient governance may prevent fair distribution. This is often

compounded by limited education of the population, including

its leaders, by unfair trade practices of the developed nations,

and at times by well-meaning but ill-advised help from outside

agencies.

13-15

In addition, in sub-Saharan Africa, there is a huge

deficit of all types of skilled medical personnel.

16

Treatment of congenital heart disease by surgery or

interventional cardiac catheterisation will always be relatively

expensive, and expense will always be a major barrier to

achieving good cardiac care of these children. This problem

is not unique to congenital heart disease, and treatment of

some non-cardiac diseases such as cancer, AIDS, drug-resistant

tuberculosis and some chronic diseases may be as expensive.

Unfortunately, attempts to alleviate poverty have had limited

success. Nevertheless there are several strategies that can help

to improve cardiac care. Because the specific problems may

differ between countries, the mix of strategies may also need to

be different.

Easing the burden of congenital heart disease can be divided

into specific cardiac approaches that can be used on a near

and mid-term time scale, and a more general socio-economic

approach that will take much longer to implement. There

are several models for the cardio-specific goals for treating

congenital heart disease in underdeveloped countries, and they

are discussed in detail by Hewitson and Zilia.

6

TABLE 2. ESTIMATES OF POTENTIAL MONEY TO SPEND ON

CHILDRENWITH CHD IN SINGAPOREAND NIGER. THE GDP

VALUESARE CORRECTED FOR LOCAL COST OF LIVING

Country

CHD/million

population

CHD/million

wage

earners

GDP per

capita

GDP/CHD

Singapore

~100

~120

$63 000

$525

Niger

~500

~850

$1 000

$0.85

TABLE 3. REPRESENTATIVE COSTS. DATA TAKEN FROM

KUMARAND BALAKRISHNAN

4

AND PASQUALI

ET AL

.

5

Service

Africa India

USA

Open-heart surgery

US$10 000 $5 000 $12 000–50 000

128-slice CT angiogram

-

$350

$4 000

Colour Doppler echocardiography $100

$30

$200

TABLE 4. RATIO OF CARDIAC SURGEONS TO POPULATION

ON DIFFERENT CONTINENTS

Continent

Ratio

cardiac

surgeons:population

North America

1:3.5 million

Europe

1:3.5 million

South America

1:6.5 million

Asia

1:25 million

Africa

1:38 million

Fig. 6. Distribution of cardiovascular centres in selected

countries and continents. The area of the bubble is

proportional to the population.