CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 4, May 2013

144

AFRICA

The least appealing is to have the child and parents go where

experts can treat the child optimally. This option is available to

only a few privileged and wealthy families and does nothing to

help the majority of people in the country. A second slightly

more productive model is to have teams of doctors, nurses and

technicians go to a country for a few weeks, and treat a set

of patients who have been selected beforehand. This certainly

benefits more children, but their follow up may be inadequate,

the majority of children with congenital heart disease remain

untreated, and this model does little to improve medical services

in the country.

A better model would be to have these teams come to a

country and help train local doctors, nurses and technicians,

so that when the visitors leave, a functioning medical service

is in place locally. This course, however, involves substantial

investment by the host country that may be unwilling or unable

to maintain this degree of sophisticated medical care. Developing

locally low-cost substitutes for expensive imported products may

reduce some of this disadvantage.

For long-term socio-economic goals, larger issues than

treatment of congenital heart disease come into play. It is far

from clear that children with congenital heart disease should

get preferential use of scarce resources. In underdeveloped

countries, congenital heart disease plays a minor role in child

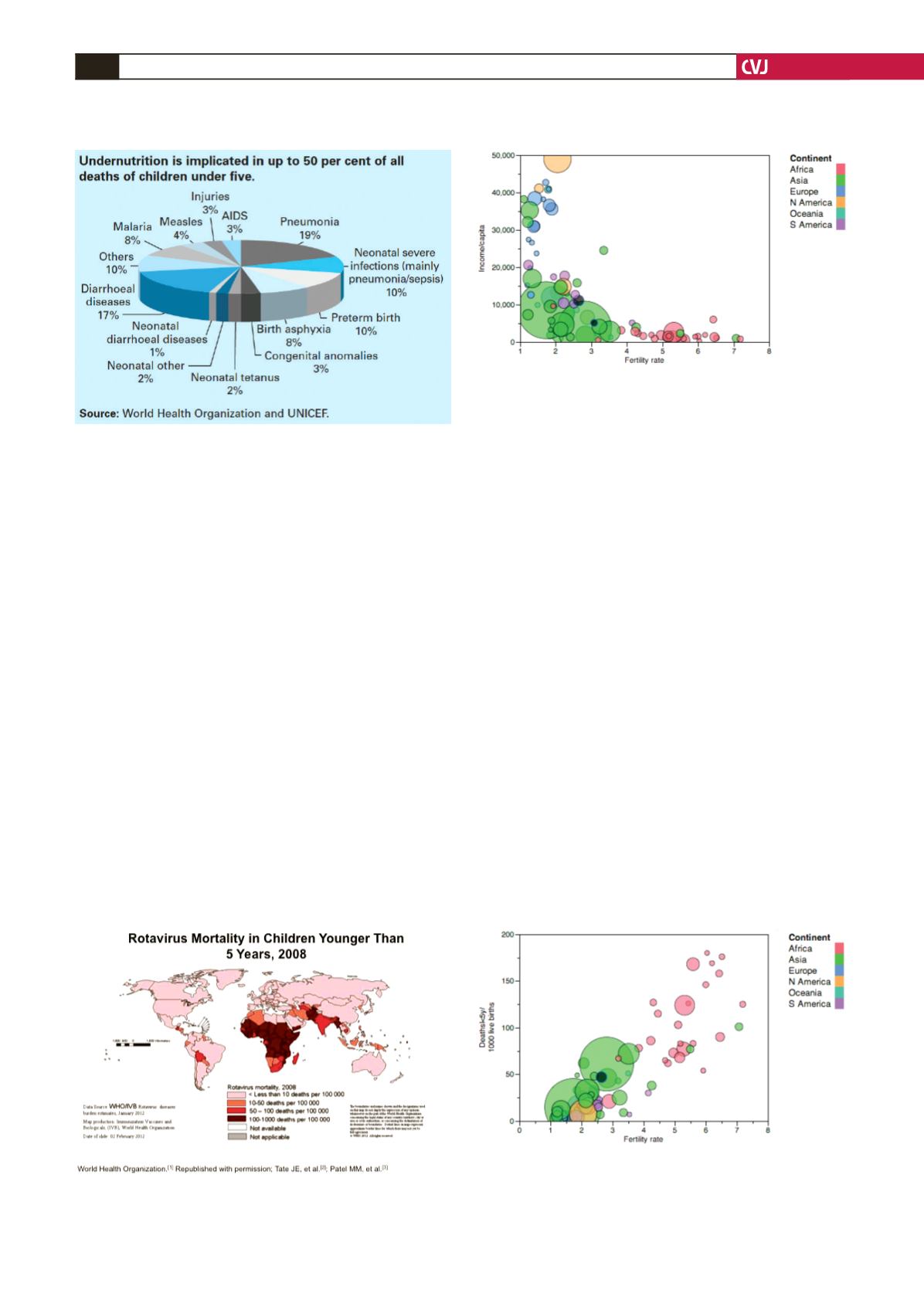

morbidity and mortality (Fig. 7).

As shown in Fig. 7, congenital anomalies of all types account

for only 5% of deaths, compared with 8% for malaria, 4% for

measles, 17% for diarrhoeal diseases, and 29% for pneumonia

and other infections, all of which are easier and cheaper to

prevent or treat than are congenital heart diseases, and would

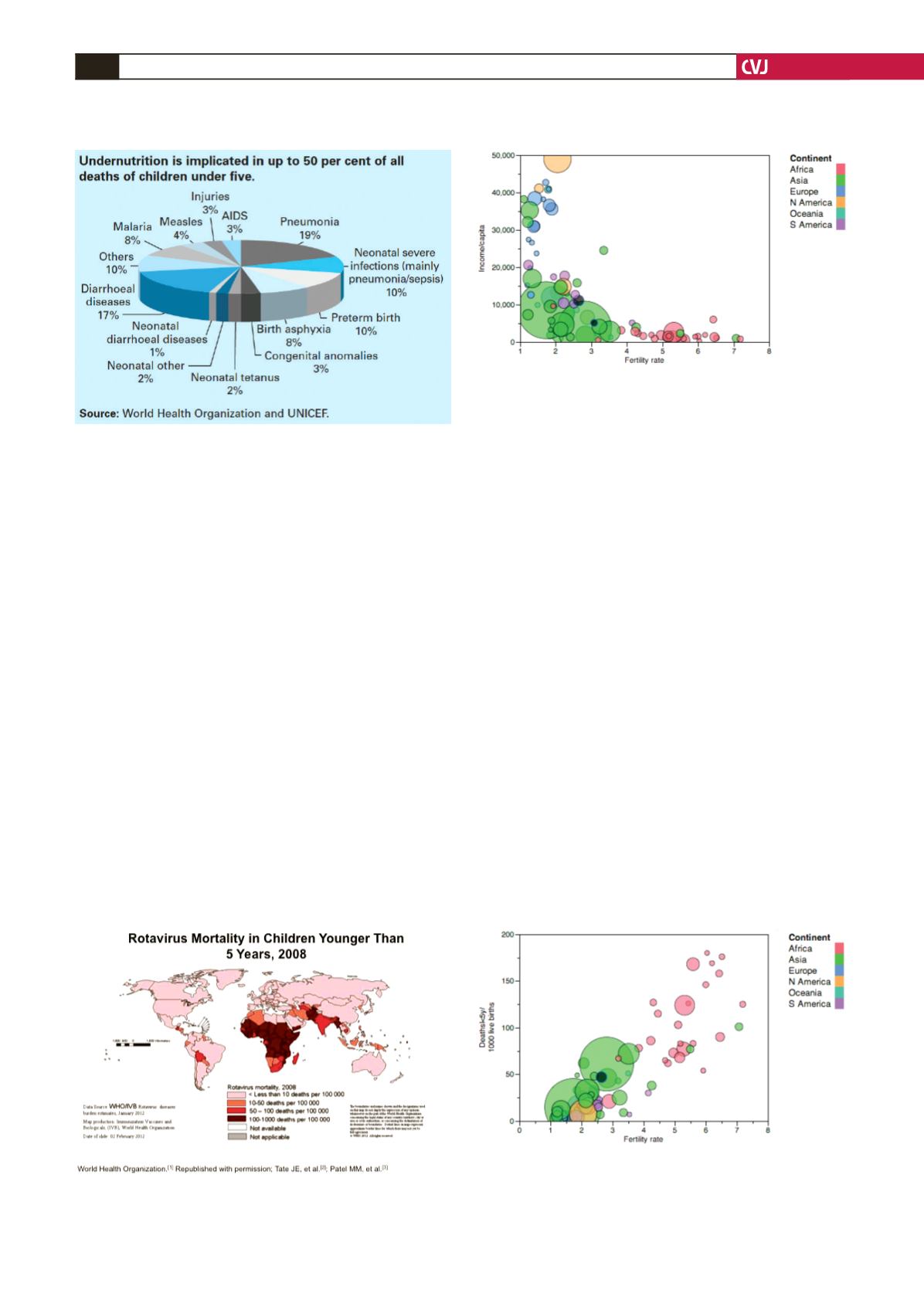

be a better way to invest scarce resources. Fig. 8 shows, for

example, the enormous death rate from rotovirus disease, for

which an excellent and low-cost vaccine is now available but not

yet extensively used.

Finally, in this list of preventable diseases, we should mention

rheumatic heart disease. Although its prevalence is not well

defined, it probably affects as many patients as do all forms

of congenital heart disease, including bicuspid aortic valves.

Inasmuch as rheumatic heart disease usually follows repeated

episodes of acute rheumatic fever, and that treatment of acute

streptococcal pharyngitis with penicillin is cheap and effective,

this would be an excellent field into which to put scarce

resources.

6

Treating congenital heart disease, however, is always going

to be expensive, and it may be worth giving more thought to its

prevention. An approach that has been shown to be effective in

a variety of countries is to educate women and improve efforts

for family planning. The relationships between excessive fertility

Fig. 7. Causes of global mortality in children under five

years old.

Fig. 8. Distribution of rotovirus mortality across the

world. Reproduced with permission from the World

Health Organisation.

Fig. 10. Fertility rate versus deaths under five years of

age per 1 000 live births. The area of the circle is propor-

tional to the population. There is a direct relationship

between fertility rate and child mortality, with African

countries being worst off.

Fig. 9. Fertility rate versus income per capita for several

countries on different continents. The continents are

colour coded, and the area of the circles is proportional

to each country’s population. Note that countries in

Africa with high fertility rates are at the lowest end of the

income scale.