CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 27, No 6, November/December 2016

AFRICA

371

activity, walking for travel, absolute dietary intake or DQI-I

between BMI groups (data not shown). Those who smoked at

baseline had a significantly higher BMI than those who did not

smoke.

Baseline housing density and asset index were not associated

with change in body weight, body composition or body fat

distribution. By contrast, other SES variables at baseline and

the changes in these variables were associated with changes in

body weight or changes in body composition over the follow-up

period (Table 3). Baseline and changes in access to sanitation and

employment had siginficant effects on weight gain over the 5.5

years, while education and contraceptive use did not.

Nulliparty had significant associations with changes in body

weight as well as changes in body fat distribution. Parity was

associated with redistribution of fat mass, with larger decreases

in appendicular fat mass (percentage of total fat mass) (–3.1

±

2.9 vs –1.5

±

2.7%,

p

=

0.040) and gynoid fat mass (percentage of

total fat mass) (–1.1

±

1.0 vs –0.5

±

1.2%,

p

=

0.088), and larger

increases in trunk fat mass (percentage of total fat mass) (3.69

±

3.5 vs 1.9

±

3.1%,

p

=

0.044) and trunk:leg ratio (0.19

±

0.2 vs

0.08

±

0.1%,

p

=

0.004) in the nulliparous women compared to

the women with children at baseline.

Furthermore, those women who were still nulliparous at

follow up (

n

=

9) increased their body weight significantly more

over the 5.5-year follow-up period than their childbearing

counterparts (

p

=

0.001). There was a trend for those who

had children over the 5.5-year period to increase their body

weight less than those who already had children, but it was not

significant after adjusting for baseline age and BMI. Those who

increased their education level (

n

=

11) had a greater increase

in relative trunk fat mass (percentage of fat mass) compared to

those who did not (

n

=

53) (

p

=

0.035).

Dietary intake and physical activity at baseline, and baseline

and follow-up smoking and alcohol intake were not associated

with changes in body composition (data not shown).

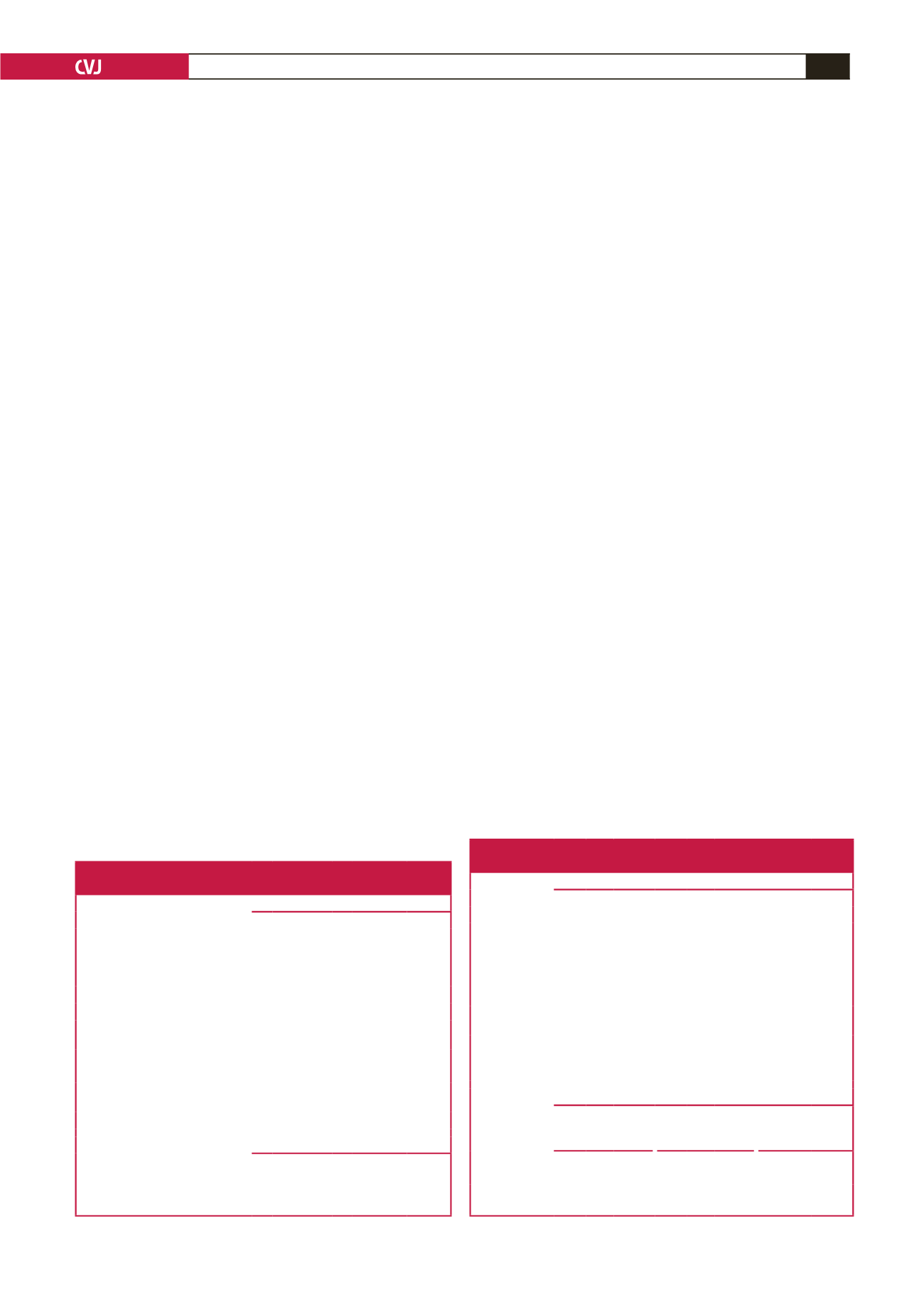

Multiple regression analysis was used to explore the

independent determinants of the changes in body weight and

body fat distribution over the 5.5-year follow-up period (Table

4), based on the significant univariate analyses described above.

Based on the regression model, increasing body weight over time

was associated with a lower baseline BMI, being nulliparous at

baseline, not having children during the follow-up period, lack

of household sanitation at baseline and improved sanitation

at follow up. This model explained 51% of the variance in the

change in body weight (

p

<

0.001). The model that explained

the greatest variance in the change in relative trunk fat mass

(percentage of fat mass), change in trunk:leg ratio and change

in relative gynoid fat mass (percentage of fat mass) (model B)

included only baseline BMI and being nulliparous at baseline.

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that lower BMI and

nulliparity, together with sanitation as a proxy for SES, were

significant determinants of weight gain and change in body fat

distribution over a 5.5-year period in a sample of free-living peri-

urban black SA women. In addition, younger women increased

their body weight more than their older counterparts, but this

association was not independent of baseline BMI.

The finding that there was an inverse relationship between

baseline BMI and weight gain is similar to other studies in

HICs. Few researchers have highlighted the effect of baseline

BMI as a predictor of future weight gain. Brown

et al

.

5

showed

that a baseline BMI of 25–30 kg/m

2

, in conjunction with a high

energy intake, was a significant determinant of weight gain over

five years in middle-aged Australian women. Another study in

the USA reported greater weight gain in those who were both

younger and who had a lower baseline BMI.

4

In addition, this

study showed that a lower baseline BMI was associated with a

greater redistribution of fat from the periphery to the central

depots over time. The women with a lower BMI may have

a higher capacity for increasing body weight and increased

centralisation of fat mass over time. This highlights a group

that is at increased risk and should be targeted for future

interventions aimed at preventing an increase in body weight

and centralisation of fat mass over time, due to the associated

negative cardiometabolic outcomes.

18

Table 4. Multivariate models for changes in

body composition over the 5.5-year period

Change in body weight (kg)

Variable

β

SEE

p-

value

Baseline BMI

–0.24

0.13

0.016

Presence of

running water

and a flush toilet

–0.28

2.66

0.023

Improvement in

sanitation (toilet

and water)

0.30

2.41

0.005

Child/children at

baseline

–0.42

2.07

0.000

Children over

follow-up period

–0.25

2.12

0.025

R

2

=

0.51,

p

<

0.001 VIF: 1.25.

Change in body fat distribution

Variable

Δ

Trunk FM (% FM)

(

R

2

=

0.43) (

p

<

0.001)

Δ

Trunk:leg

(

R

2

=

0.35) (

p

<

0.001)

Δ

Gynoid FM (% FM)

(

R

2

=

0.20 (

p

=

0.001)

VIF

1.02

1.02

1.02

β

SEE

p-

value

β

SEE

p-

value

β

SEE

p-

value

Baseline BMI –0.61 0.04

<

0.001 –0.47 0.00

<

0.001 0.40 0.02 0.001

Child/children

at baseline

–0.34 0.69 0.001 –0.42 0.03

<

0.001 0.22 0.27 0.022

Table 3. Change in body weight and trunk fat mass in response to

differences in SES/behaviour/lifestyle variables

SES/behaviour/lifestyle variable

Change in body weight (kg)

n

Yes

n

No

p-

value

Access to inside running water at

baseline?

16 1.7

±

11.2 45 8.8

±

8.8 0.012

Access to inside flush toilet at

baseline?

16 2.3

±

12.1 45 8.5

±

8.8 0.032

Employed at baseline?

20 10.2

±

10.9 41 5.1

±

8.7 0.050

Grade 12 at baseline?

21 7.2

±

8.8 40 6.5

±

10.3 0.803

Hormonal contraceptive use at

baseline?

30 8.0

±

8.9 31 5.5

±

10.6 0.982

Nulliparous at baseline?

25 10.7

±

9.5 36 3.8

±

8.9 0.005

Nulliparous at follow up?

9 16.6

±

7.2 52 5.4

±

9.3 0.001

Improvement in sanitation over

time?

14 15.1

±

7.5 44 4.8

±

9.4

<

0.001

Loss of employment over time?

8 11.7

±

6.4 53 5.8

±

11.6 0.043

Change in trunk fat mass (% TFM)

n

Yes

n

No

p

-value

Improvement in level of education

over time?

11 2.2

±

3.3 53 4.6

±

3.1 0.035

Nulliparous at baseline

25 3.7

±

3.5 36 1.9

±

3.1 0.044