CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 4, July/August 2017

AFRICA

219

regurgitant lesions. The reason why some patients develop pure

MS is unknown.

4

Differences in the interaction of host immunity,

initial or recurrent streptococcal infections and chronic exposure

of the valve leaflets to abnormalities of haemodynamic flow may

account for these difference in morphology and dictate which

lesion may predominate.

The current data confirm that there has been a dramatic

decline in the incidence of rheumatic carditis in the population

of Soweto, although the reasons for this are not entirely clear.

The striking trend toward a substantial decline in ARF has

also been documented in the paediatric section of Baragwanath

Hospital, with a reduction from 64 cases per year in 1993 to three

per year in 2010.

16

This decline was attributed to improved socio-

economic status and better access to healthcare.

16

Thirty years ago McClaren

et al

. (by auscultation alone)

reported a RHD incidence of 6.9/1 000 among school children in

Soweto.

16

Recently, Engel

et al

. (by echocardiography) reported

a RHD incidence of 20.2/1 000 cases among scholars in the

Bonteheuwel and Langa communities of Cape Town, with the

prevalence being higher in poorer communities.

17

Data from

other areas of the country are scarce; the REMEDY study did

not report on the incidence or prevalence of RHD. However,

25.8% (863/3343) of participants were from upper middle-

income countries (South Africa and Namibia).

18

Concomitant with the decline in rheumatic fever, diseases

associated with a Western lifestyle and urbanisation have

emerged. A considerable number of patients with rheumatic MR

currently have co-morbidities of hypertension (52%) and HIV

(26%). These findings differ considerably from previous studies

conducted in our institution. These co-morbidities mandate a

careful assessment of the patient’s clinical presentation, since

symptoms may not be solely attributed to MR; elevated blood

pressure could overestimate the echocardiographic severity of

MR and left ventricular dysfunction may be attributed to

concomitant HIV infection rather than volume overload.

The morphological abnormalities of the mitral apparatus

(thickened and shortened subvalvular apparatus) and the nature

of leaflet dysfunction (Carpentier IIIa) described in the current

population has diagnostic implications. MR jets that are eccentric

may require careful off-axis imaging to accurately delineate

the full extent of the colour jet. Furthermore, an integrated

evaluation of MR severity is mandatory due to the limitations of

quantitative Doppler in some instances of eccentric jets.

Our findings also have important therapeutic implications in

terms of surgery for rheumatic mitral regurgitation. Mitral valve

repair has several advantages compared to replacement, including

lower peri-operative mortality rate, better preservation of post-

operative left ventricular function, no need for anticoagulant

therapy, and a safer pregnancy.

19

In younger patients, absence

of advanced subvalvular and valvular thickening, calcification

and restriction of motion make it likely that a variety of repair

techniques would be successful. In the older, contemporary

population that we have described, the need for valve repair is

less pressing compared to younger patients and the probability

of surgical failure higher, given the presence of extensive

subvalvular and valvular disruption.

An important observation was the high frequency of

concurrent TV leaflet abnormality and tricuspid annular

dilatation. These abnormalities were not reported by Marcus

et al

.

6

and no data on surgical repair were given. Our findings

suggest that once rheumatic MR is identified, careful assessment

of the morphology and function of TV is mandatory when

selecting patients who will undergo mitral valve surgery. This

strategy may reduce the likelihood of the late consequences of

unrepaired TR in rheumatic patients, which has been previously

highlighted.

20

Late TR causes increased morbidity and mortality

rates despite the presence of successful mitral valve surgery, and

in addition, a second operation to correct the residual TR carries

increased mortality rates.

20

There are several limitations to this study. The initial diagnosis

of HF was made outside of our clinic with no uniform criteria

applied. None of the patients had surgery, so that surgical

confirmation of the echocardiographic abnormality was not

possible. Finally, the population studied may not truly reflect

the nature of the disease in younger rural populations where

a greater prevalence of acute rheumatic carditis may be found.

Conclusion

The modern cohort of patients with rheumaticMRwas older, had

less acute rheumatic fever and greater associated co-morbidities.

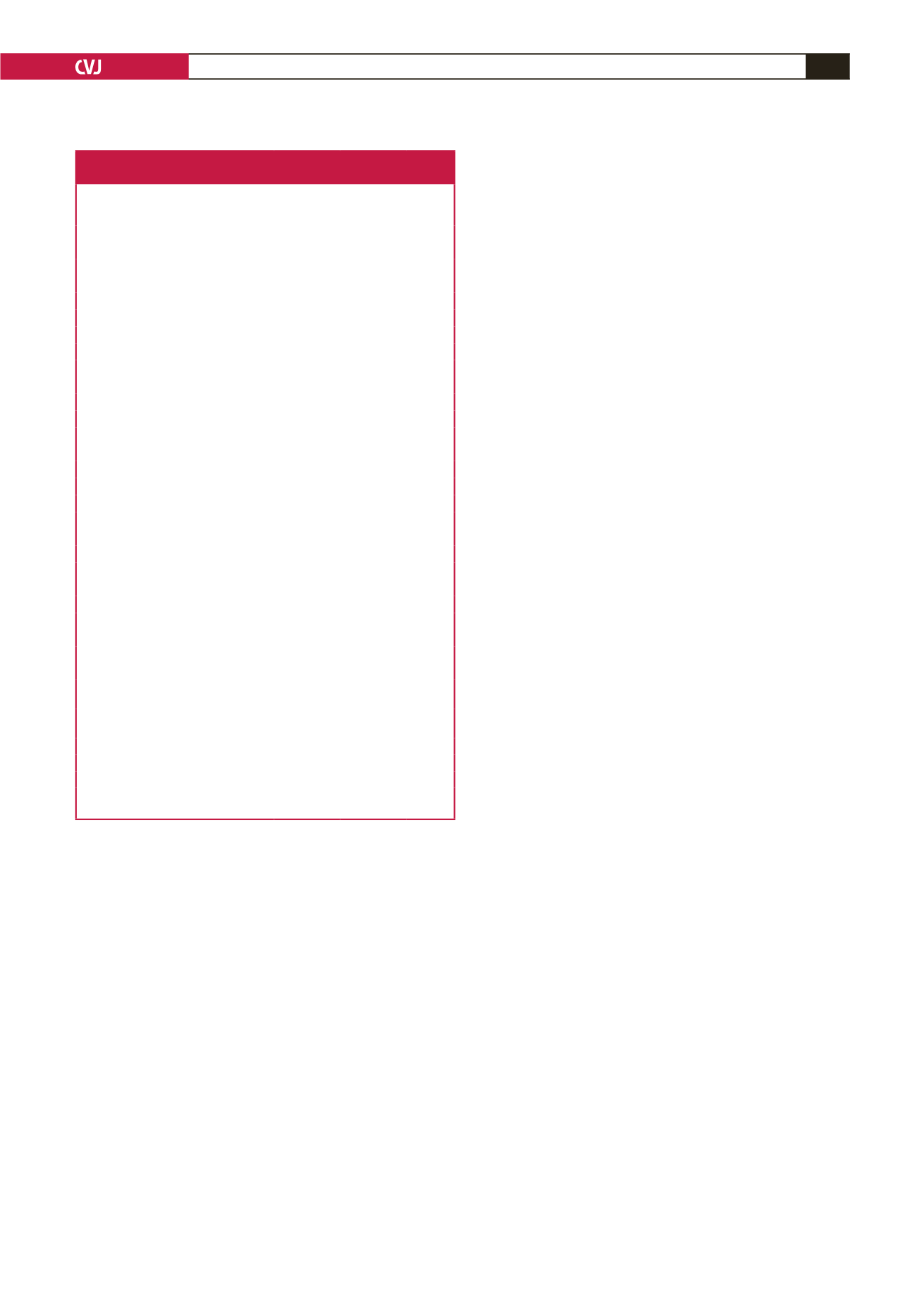

Table 4. Clinical and echocardiographic features according to the

presence or absence of hypertension*

Variables

Hyper-

tension

(

n

=

45)

Normo-

tension

(

n

=

39)

p

-value

Clinical parameters

Age (years)

51.7

±

11.1 35.1

±

14.2

<

0.0001

Female (%)

86

82

0.62

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg)

127.9

±

8.4 119.5

±

12.8 0.0008

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)

79.2

±

8.5 74.2

±

8.8 0.01

Body mass index (kg/m

2

)

28.6

±

6.1 25.0

±

5.8 0.01

Body surface area (m

2

)

1.7

±

0.2

1.7

±

0.2 0.21

NYHA functional class (I/II and III)

29/71

56/44

0.03

Left ventricle

LV end-diastolic diameter (mm)

52.4

±

8.4 58.3

±

9.8 0.004

LV end-systolic diameter (mm)

39.7

±

9.5 43.2

±

10.9 0.12

Interventricular septal diameter (mm)

9.0

±

2.3

8.9

±

4.6 0.97

Posterior wall diameter (mm)

9.1

±

1.6

8.1

±

1.3 0.0009

End-diastolic volume indexed (mls/m

2

)

†

87.7

±

29.9 100.9

±

32.0 0.05

End-systolic volume indexed (mls/m

2

)

†

35.9

±

17.7 46.1

±

27.4 0.046

LV mass indexed (g/m

2

)

†

100.1

±

39.4 110.4

±

40.2 0.24

Relative wall thickness

0.4

±

0.1

0.3

±

0.1 0.0001

LV ejection fraction (%)

58.4

±

12.6 58.1

±

13.1 0.91

Ejection fraction ≥ 60%

24

24

Ejection fraction

<

60%

20

16

0.61

Average E/E

′

(cm/s)

19.2

±

10.9 17.7

±

8.9

E

′

(cm/s)

7.4

±

2.5

9.9

±

3.4 0.006

E/A ratio

1.3

±

0.6

1.6

±

0.6 0.008

Left atrium

Left atrial volume indexed (ml/m

2

)

†

57.6

±

24.1 83.37

±

67.7 0.42

Right ventricle

Right ventricle S

′

(cm/s)

14.6

±

15.6 11.2

±

2.5 0.18

Pulmonary artery systolic pressure

(mmHg)

33.7

±

19.2 37.9

±

16.1 0.28

Tricuspid regurgitation (none/mild/

moderate to severe) (%)

38/36/26

33/31/36 0.46

Mitral regurgitation severity

Moderate mitral regurgitation (%)

82

56

Severe mitral regurgitation (%)

18

44

0.009

*Data are presented as mean

±

SD or %.

†

Values are indexed to body surface

area. LV: left ventricle; NYHA: New York Heart Association.