CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 4, July/August 2017

AFRICA

225

identified PE is presented in Table 8. Fisher’s exact test showed

no significant association between HIV status of the patient and

the presence of each of the complications.

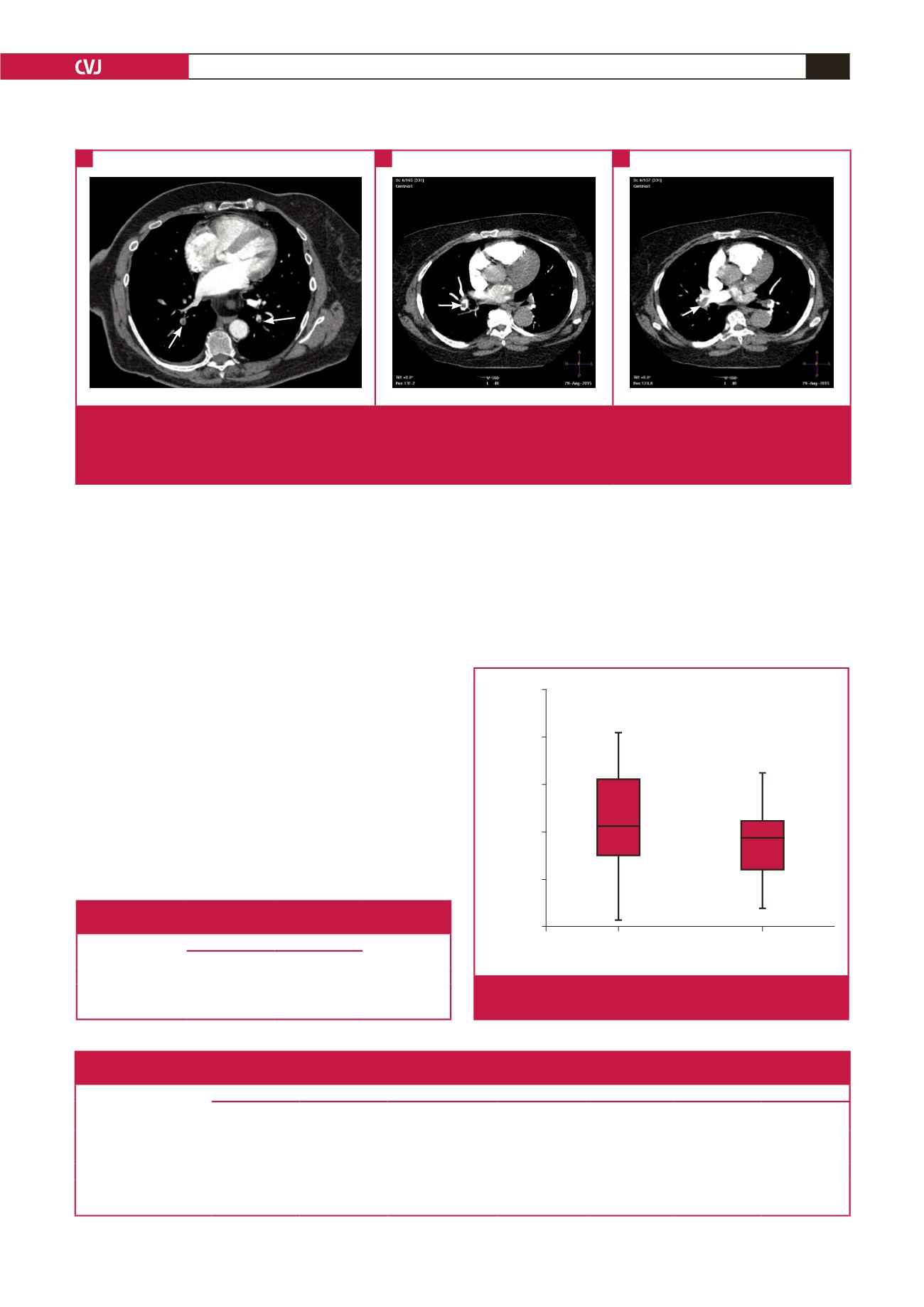

Comparisons between HIV-positive and -negative groups

with regard to Qanadli scores, and RV:LV and PA:AO ratios

are demonstrated in Figs 5–7. The Mann–Whitney

U

-test

demonstrated no significant differences between HIV-positive

and -negative categories for any of the above variables (

p

=

0.440,

p

=

0.611 and

p

=

0.191, respectively) in patients with PE.

Discussion

Prevalence of PE in a CTPA population

Previously published studies have reported the general prevalence

of PE in hospital populations. In our study, we differ in that we

report the prevalence of PE in a population of patients who

underwent CTPA for suspected PE. Similar studies evaluating

the presence of PE in a CTPA population are sparse. A study

in Cameroon (Africa), undertaken at a university-affiliated

hospital, demonstrated a CTPA incidence of PE of 32.4% over

a two-year period.

6

Our CTPA prevalence of PE is comparable

at 26%.

CTPA is a high-dose and costly study but can be performed at

most regional, some district and all tertiary institutions in South

Africa. Approximately 10 CT scans per month performed at our

study hospital were CTPAs, yet only a quarter of patients imaged

had positive findings of PE.

Table 8. Comparison of frequency (with percentages in brackets) of parenchymal and pleural complications present in

HIV-positive and -negative patients with pulmonary embolism (

n

=

33).

HIV status

Complications

Atelectasis

Consolidation

Wedge-shaped pleural-

based density

Ground-glass

opacity

Pleural effusion

None

*

Total

HIV positive,

n

(%)

10 (45.45)

15 (68.18)

4 (18.18)

9 (40.91)

10 (45.45)

2 (9.09)

22 (100)

HIV negative,

n

(%)

7 (63.64)

5 (45.45)

1 (9.09)

7 (63.64)

4 (36.36)

0 (0)

11 (100)

Total,

n

(%)

17 (51.52)

20 (60.61)

5 (15.15)

16 (48.48)

14 (42.42)

2 (6.06)

33 (100)

p

-value

0.465

0.270

0.643

0.282

0.719

0.542

*

Subjects who reported none of the named complications

Table 7. Comparison of the severity of the Qanadli score between

HIV-positive and -negative patients (

n

=

33)

HIV status

Qanadli score

Total

< 40%

≥ 40%

HIV positive,

n

(%)

10 (45.45)

12 (54.55)

22 (100)

HIV negative,

n

(%)

7 (63.64)

4 (36.36)

11 (100)

Total,

n

(%)

17 (51.52)

16 (48.48)

33 (100)

HIV status

HIV positive

HIV negative

Qanadli score

100

80

60

40

20

0

Fig. 5.

Differences between HIV positive and negative

according to Qanadli scores (

p

=

0.440).

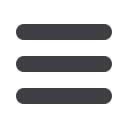

Fig. 4.

The CTPA appearances, showing the different degrees of obstruction in the lobar and segmental arteries, are depicted in

the series of images. (A) Axial CT scan showing partially occlusive thrombi (short arrows) in the right and left lower lobe

basal segmental arteries. (B) Axial CT scan showing partially occlusive thrombus (long arrow) in the right lower lobe artery.

(C) Axial CT scan showing totally occlusive thrombus (long arrow) in the right lower lobe artery.

A

B

C