CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 6, November/December 2017

358

AFRICA

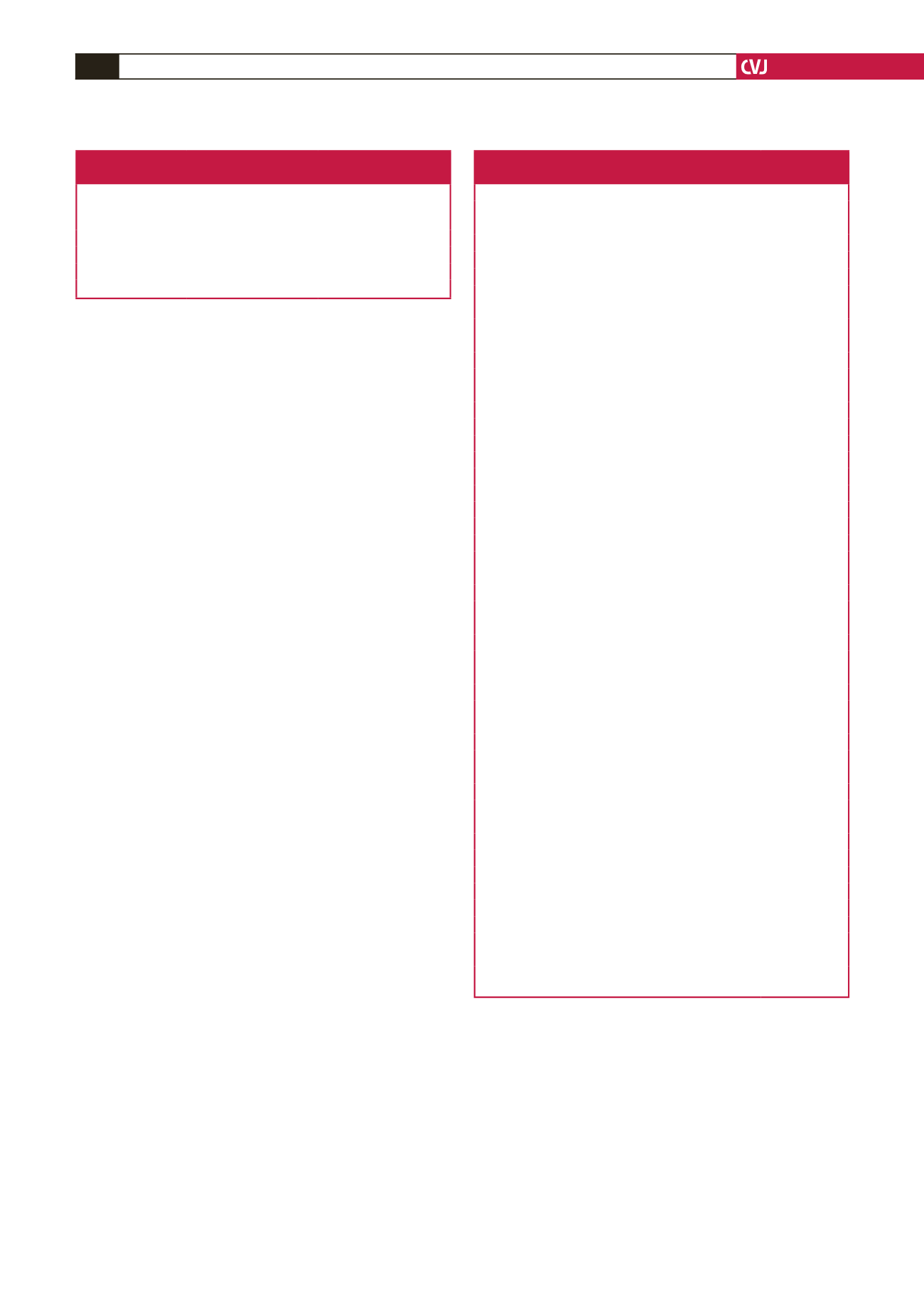

of patients had moderate and intermediate PE probability,

respectively (Table 3).

Laboratory tests deviated from normal in 68% of patients;

their positivity rates and cut-off values are shown in Table 4.

D-dimer, troponin and BNP levels were positive in all tests

with available results. More than half of the patients (54%)

had abnormal results in their arterial blood gasometry (ABG),

namely hypoxaemia in 34% and acute respiratory alkalosis in

20% of patients.

About a quarter of patients (13 patients) had normal chest

radiography. The electrocardiogram was normal in only 22% of

patients and the classic S1Q3T3 pattern was found in only 18%.

RV enlargement (20%) and RV hypokinesia (8%) were the main

echocardiographic findings in our study. We documented the

presence of deep-vein thrombosis by Doppler ultrasound in 20%

of patients.

PCTA changes were correlated with haemodynamic stability

at admission in all patients; 28% had massive PE, of whom 20%

were haemodynamically unstable; 36% had sub-massive PE and

showed a statistically significant rate of haemodynamic stability

at admission (28 vs 8%,

p

=

0.018). In 36% of patients there was

low-risk PE (Table 5). All patients were stratified according to

the pulmonary embolism severity index and 30% of the patients

had a very high risk of mortality (Table 6).

Heparins were the most common form of in-hospital

anticoagulation. Unfractionated heparin was used in 32% of

patients for 5.4

±

2.1 days. Low-molecular-weight heparins

were used in 44% of patients for 6.2

±

3.7 days. Among these

patients, 70% used oral anticoagulation with warfarin and 6%

used new oral anticoagulants (NOAC) (Table 7). Thrombolytic

therapy was used in 18% of the patients. In 12 patients, it was not

possible to determine the type of anticoagulant used or whether

they used thrombolytic therapy, due to the unavailability of data.

There were complications in 38% of the patients; 15 had

respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and seven

had cardiogenic shock (Table 8). The 24-hour and in-hospital

mortality rates were 2.5 and 20%, respectively. There were

15 deaths, of which five occurred in the first 24 hours after

admission.

Considering the study criteria, three patients had a fatal

outcome and were not included (no imaging confirmation of

PE). However, they showed a high clinical probability for PE and

alternative diagnoses were less likely.

Discussion

The study results characterise the clinical profile of patients

with PE admitted at our hospital. The presented data refer to

the current clinical practice without any interference in medical

procedures. The high clinical suspicion associated with the

immediate availability of pulmonary CT angiography and other

diagnostic tests allowed us to confirm PE cases and exclude

other differential diagnoses. This context has added greater

consistency to the study results.

According to Tambe and colleagues in Cameroon,

10

it was

found that PE is not a rare disease in sub-Saharan African

populations. Institutional unavailability of CT angiography may

favour sub-detection of the disease in some geographic areas.

10

The median age observed in our study was 50.5

±

17.8 years,

similar to that described in the EMPEROR study

11

(56.5

±

18.1

years), and lower than some observational studies describing

Table 3. Pulmonary embolism risk stratification according to the

modifiedWells and Geneva revised scoring systems

PE probability

Wells scoring system

n

(%)

Geneva scoring system

n

(%)

Low

7 (14)

5 (10)

Moderate

28 (56)

Intermediate

29 (58)

High

15 (30)

16 (32)

Total

50

50

Table 4. Frequency and positivity of the auxiliary diagnostic

tests in patients with pulmonary embolism

Diagnostic tests

Number (%)

Laboratory tests

White blood cells (

>

10 × 10

9

cells/l)

14 (28)

LDH (

>

400 U/l)

10 (20)

D-dimers (

>

500 μg/l)

4 (8)

Troponins (

>

0.1 ng/ml)

4 (8)

ESR (

>

10 mm in men,

>

20 mm in women)

3 (6)

BNP (

>

500 pg/ml)

1 (2)

Normal

16 (32)

Arterial blood gasometry (ABG)

Hypoxaemia

17 (34)

Acute respiratory alkalosis

10 (20)

Normal

13 (26)

Absent ABG

13 (26)

Chest radiography

Pulmonary parenchymal infiltrates

7 (14)

Hampton sign

6 (12)

Pleural effusion

4 (8)

Cardiomegaly

2 (4)

Pneumothorax

1 (2)

Westmark sign

1 (2)

Changes not related to PE

5 (10)

Normal

13 (26)

Absent chest radiography

12 (24)

Electrocardiogram

S1Q3T3 pattern

9 (18)

Non-specific repolarisation changes

6 (12)

Right bundle branch block

4 (8)

Right ventricular hypertrophy

1 (2)

Right cardiac axis deviation

1 (2)

Sinus tachycardia

1 (2)

Changes not related to PE

6 (12)

Normal

11 (22)

Absent ECG

11 (22)

Echocardiogram

Enlarged right heart chambers with or without thrombus

10 (20)

Right ventricular hypokinesis

4 (8)

Pulmonary hypertension

3 (6)

Persistent foramen ovale

2 (4)

McConnel sign

2 (4)

Changes not related to PE

4 (8)

Normal

9 (18)

Absent echocardiogram

17 (34)

Limb Doppler ultrasound

Deep-vein thrombosis

10 (20)

Normal

33 (66)

Absent Doppler ultrasound

7 (14)

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase enzyme; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate;

BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide.