CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 31, No 5, September/October 2020

AFRICA

255

years compared to 5.2% in those 75 years or older.

16

In another

study in 1 470 NSTEMI patients from the Taiwan nationwide

registry, older age

≥

75 years increased mortality rate 4.9 times

compared to patients 45–64 years of age.

17

Our study represents the high risk elderly patients admitted

with a diagnosis of ACS face in a contemporary cardiology

clinic. About 71% of our patients were characterised by a

GRACE risk score higher than 150, and more than 70% had a LV

ejection fraction lower than 50%. As a treatment strategy, about

60% of our patients were managed invasively. In the literature,

angiography rate in this population was slightly lower than in our

study. In European and US registries, the reported proportion of

elderly patients assigned to an invasive strategy was 50 to 33% in

patients aged beyond 70 and 80 years, respectively.

15

Our analysis of elderly patients with ACS demonstrated that

an invasive strategy was associated with a lower mortality rate at

follow up of a maximum of 61 months in comparison with an

initial conservative strategy. Almost twice the risk of mortality

has been seen with the conservative strategy. Similar to our

results, Tegn

et al

. reported in their After Eighty study, an open-

label, multicentre study targeting NSTEMI patients older than

80 years, that an invasive strategy was superior to a conservative

strategy in reduction of composite events of death, myocardial

infarction, stroke and the need for urgent revascularisation (40.6

vs 61.4%, hazard ratio 0.53, 95% CI: 0.41–0.69;

p

=

0.0001) at a

median follow up of 1.53 years.

18

However in another study from

Saudi Arabia, PCI had no effect on mortality rate in elderly

patients with ACS.

19

During the follow-up period, 75% of the STEMI patients

in our study died. This value was 32% in the NSTEMI/USAP

patients. This shows that STEMI has a worse prognosis than

other types of ACS in elderly patients. Similar to our results, in

another study, it was shown that STEMI increased mortality risk

about two-fold compared to NSTEMI at older ages.

20

In another

study from Switzerland from 2001 to 2012, in-hospital mortality

rate decreased and PCI use was significantly increased in older

patients.

21

Ischaemic heart disease is the leading cause of death globally.

22

Because of the growth of the elderly population, the World

Health Organisation predicts that coronary heart disease deaths

will increase by 120 to 137% during the next two decades, and a

person aged over 80 years can expect about nine remaining years

of life.

23

For this reason, a strategy on how to treat very elderly

patients is essential. The results from the present study support

an invasive strategy in octogenarians presenting with ACS.

Our study has some limitations. First, it has a retrospective,

cross-sectional design with single-centre data. Due to

the retrospective retrieval of the patient data and the low

patient numbers, our study cannot be generalised to all elderly

populations. Second, diagnosis of ACS in the elderly population

is challenging and multiple co-factors may affect cardiac enzyme

elevation, so some patients could be misdiagnosed. Finally, the

presence of multiple co-morbidities and the frailty of patients

may affect long-term mortality rates in elderly patients.

Conclusion

Guideline-based therapy should be the basic strategy for all

age groups in the presence of ACS. Within the indications, an

invasive strategy should without doubt be applied in elderly

patients. Advanced age of the patient should not be the reason

for not receiving these treatments.

References

1.

Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Measuring the global burden of disease.

New

Eng J Med

2013;

369

(5): 448–457.

2.

Alexander KP, Newby LK, Cannon CP, Armstrong PW, Gibler WB,

Rich MW,

et al

. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part I.

Circulation

2007;

115

(19): 2549–2569.

3.

Montalescot G, Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Gibson CM,

McCabe CH,

et al

. Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients

undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation

myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised

controlled trial.

Lancet

2009;

373

(9665): 723–731.

4.

Cannon CP, Harrington RA, James S, Ardissino D, Becker RC,

Emanuelsson H,

et al.

Comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in

patients with a planned invasive strategy for acute coronary syndromes

(PLATO): a randomised double-blind study.

Lancet

2010;

375

(9711):

283–293.

5.

Roule V, Blanchart K, Humbert X, Legallois D, Lemaitre A, Milliez P,

et al

. Antithrombotic therapy for ACS in elderly patients.

Cardiovasc

Drugs Ther

2017: 1–10.

6.

Puymirat E, Aissaoui N, Cayla G, Lafont A, Riant E, Mennuni M,

et

al

. Changes in one-year mortality in elderly patients admitted with acute

myocardial infarction in relation with early management.

Am J Med

2017;

130

(5): 555–563.

7.

De Luca L, Olivari Z, Bolognese L, Lucci D, Gonzini L, Di Chiara A,

et al.

A decade of changes in clinical characteristics and management of

elderly patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction admitted in

Italian cardiac care units.

Open Heart

2014;

1

(1): e000148.

8.

De Luca L, Marini M, Gonzini L, Boccanelli A, Casella G, Chiarella F,

et al

. Contemporary trends and age‐specific sex differences in manage-

ment and outcome for patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial

infarction.

J Am Heart Assoc

2016;

5

(12): e004202.

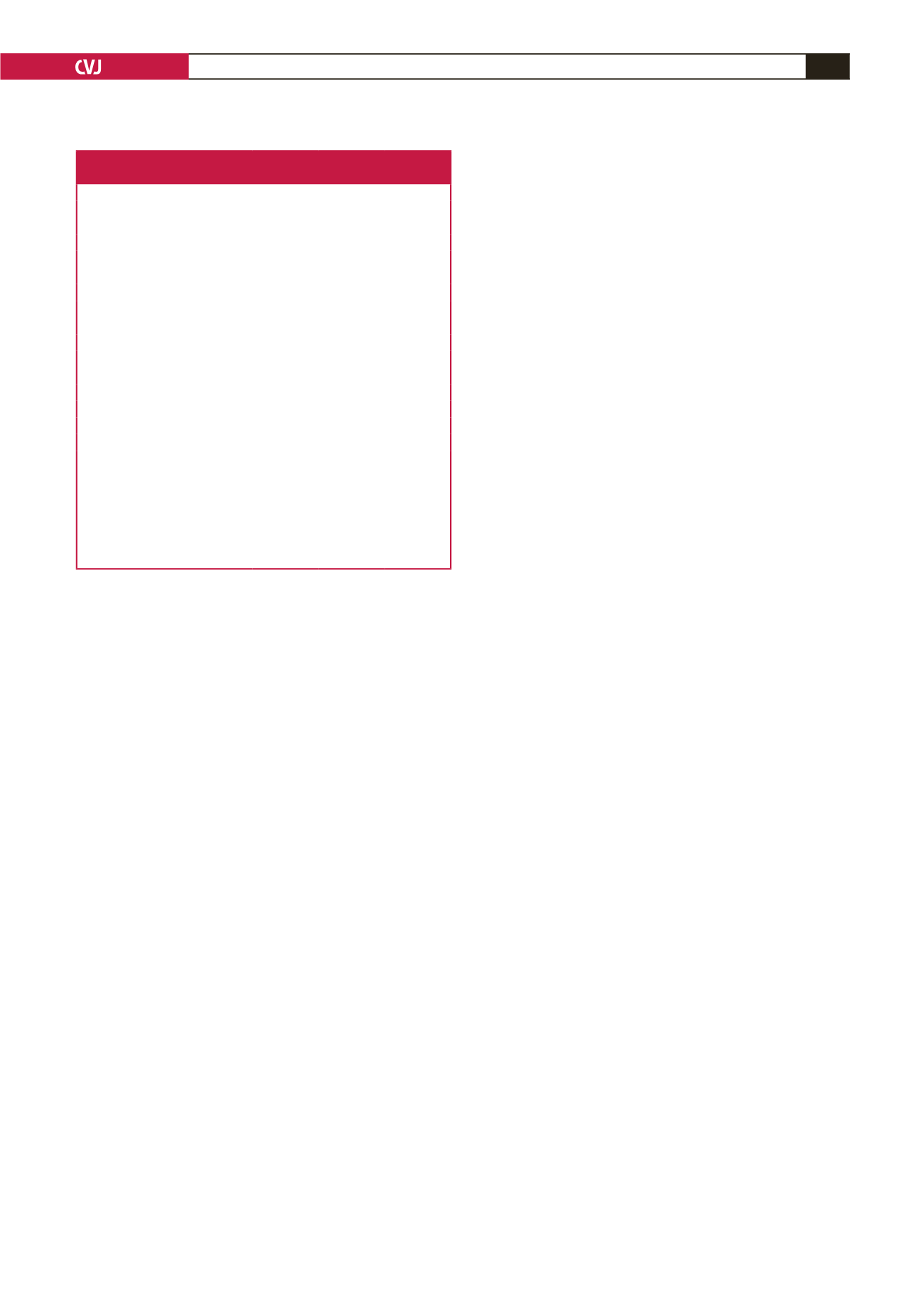

Table 3. Death predictors at the prespecified

by Cox multivariate analysis

Mortality

OR

95% CI

p

-value

Model 1

Invasive strategy*

Male

0.25

0.08–0.74

0.012

Hypertension

3.93

1.36–11.35

0.011

Ejection fraction

≤

40%***

2.65

1.11–6.32

0.027

GRACE risk score

4.49

1.66–12.10

0.003

<

150****

0.18

0.03–0.86

0.032

150–175****

0.32

0.10–0.96

0.043

ECG sinus rhythm

0.21

0.05–0.85

0.029

Model 2

Invasive strategy*

0.26

0.12–0.56

0.001

STEMI**

7.76

1.74–34.57

0.002

Ejection fraction

≤

40% ***

3.11

1.43–6.76

0.004

Heart rate (bpm)

0.98

0.96–0.99

0.013

GRACE risk score 150–175****

0.32

0.15–0.70

0.004

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*Conservative strategy as ref. **USAP as ref. ***Ejection fraction

>

40% as ref.

****Grace

>

175 as ref.

Model 1: Treatment protocols, gender, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia,

smoking, diagnosed, ejection fraction, ECG results, presentation symptoms,

GRACE risk score.

Model 2: Treatment protocols, diagnosed, ejection fraction, heart rate, ECG

results, smoking, admission SBP, presentation symptoms, GRACE risk score,

CKMB peak value, troponin peak value.