CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 31, No 5, September/October 2020

258

AFRICA

staffed by two general paediatricians with training in paediatric

echocardiography and cardiology.

The clinic screened referrals for cardiac disease and managed

children with known cardiac conditions, including CHD. Initial

assessment of patients included history, physical examination,

chest radiography and electrocardiography. Echocardiography

was performed at the discretion of the attending paediatrician if

any of the initial investigations suggested heart disease.

Patients diagnosed with CHD were managed medically,

with repeat clinic follow-up visits, including echocardiograms

as required. Patients requiring surgical correction were referred

to South Africa and, following post-surgery hospital discharge,

were managed back in Botswana.

Inclusion criteria were patients younger than 15 years of age

who were seen at the PMH paediatric cardiac clinic and who

had had at least one echocardiogram. Patients were identified

by reviewing clinic echocardiography reports and applying the

inclusion criteria. Duplicate records were deleted and only the

initial echocardiography report was retained. The list of data

points extracted included: age, gender, weight, and indication for

and result of the echocardiogram.

During data collection we noted that from May 2014,

all paediatric echocardiographs were performed by one

paediatrician. Given that this paediatrician’s record keeping

was good, all echocardiograph reports performed after May

2014 were available for analysis. This presented an excellent

opportunity to assess whether the spectrum of CHD that

had been sampled between 1 January 2010 and 31 December

2012 was similar to that seen in 2014. Hence we included a

comparator group for three months of 2014 (from 1 September

to 30 November 2014) to assess for possible sampling bias.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarised using standard descriptive statistics and

analysed using STATA version 12.0 (College Station, TX). A

p

-value of

<

0.05 was deemed significant.

To estimate the prevalence of CHD, we took two approaches:

first, for the three years from 2010 to 2012 with records from

a single paediatrician, we calculated the number of new CHD

patients seen per year. Given that this figure reflected the

echocardiography reports of one of two paediatric cardiologists,

we doubled this number to estimate the real number seen by two

paediatric cardiologists per year. Using Botswana’s 2012 annual

birth cohort of 40 856 from the Botswana Vital Statistics Report

as the denominator, we then estimated the prevalence of CHD.

For the comparator group, we used the same calculation

to estimate the prevalence of CHD: for three months of 2014,

we noted the number of unique patients with CHD. To adjust

for the fact that patients return every three to six months for

review at the clinic and that for these three months in 2014, the

paediatric cardiologist was not on leave, we multiplied this by

two to estimate the number of new unique CHD patients seen

in the year 2014. This number was then used as the numerator,

with the denominator the annual birth cohort, to estimate the

prevalence of CHD in 2014.

Results

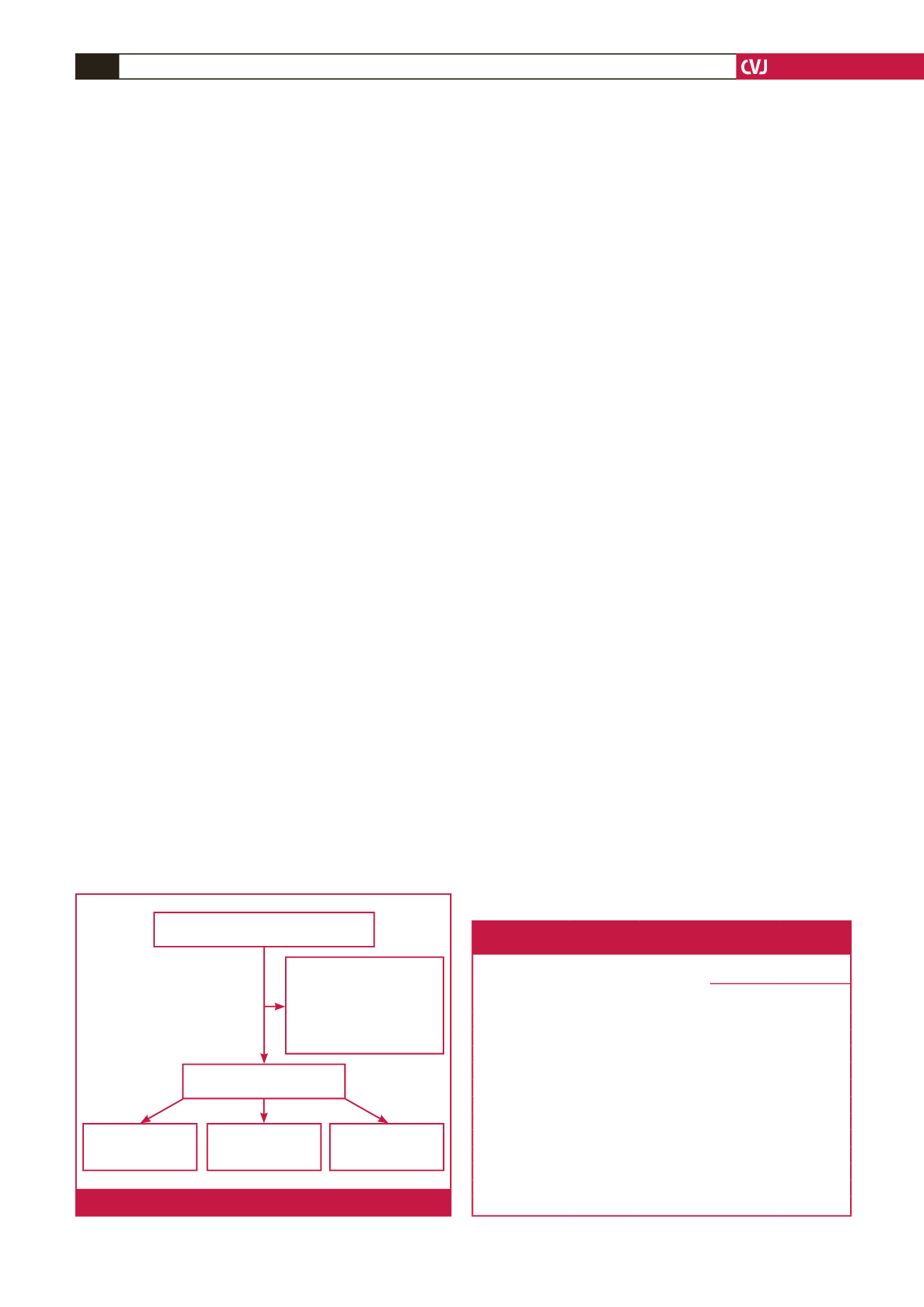

Overall, 377 subjectsmet study inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of these,

170 (45%) had CHD, 150 (40%) had normal echocardiographs

and 57 (15%) had acquired cardiac disease.

Demographics are summarised in Table 1. The median age of

the study population was 1.3 years (interquartile range 2 months

to 5.4 years) with a fairly even age distribution among children

with CHD, whereas children with acquired heart disease tended

to be in the oldest age group of 5 to 15 years (46%). Almost a

quarter (24%) of patients with CHD had a weight-for-age less

than the third standard deviation.

Indications for echocardiography are summarised in Table

2. The most common recorded indication was a known risk

factor for CHD, including trisomy 21 (

n

=

10, 11%) and other

dysmorphic features (

n

=

7, 7%). However, CHD risk factors

were not specified in the majority of patients.

The distribution of CHD types is summarised in Fig. 2.

The most common acyanotic congenital cardiac lesion was

ventricular septal defect (VSD) (50/170; 29%). The most common

cyanotic congenital cardiac lesion was tetralogy of Fallot (TOF)

(11/170; 6%).

Of the 50 VSDs, VSD type was recorded in 23 (46%) cases:

8/23 (35%) were muscular, 8/23 (35%) were membranous, 5/23

(22%) were outlet and 2/23 (9%) were inlet. VSD size was small

Total no of echocardiographs performed

during the study period = 393

Exclusions = 16:

Age > 15 years = 6

Unknown age = 7

Echocardiograph

prior to 2010 = 2

Unknown date of

echocardiograph = 4

Total no of participants

included in study = 377

No of patients with

normal echocardio-

graph = 150 (40%)

No of patients with

CHD = 170 (45%)

No of patients with

acquired lesions =

57 (15%)

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of enrolled participants.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of children with normal versus

abnormal echocardiographs

Whole study

population

(n

=

377) (%)

Normal

echocardio-

gram

(n

=

150) (%)

Abnormal echocardiogram

(n

=

227) (%)

CHD

(n

=

170) (%)

Acquired

(n

=

57) (%)

Male gender*

188 (50)

74 (49)

85 (50)

29 (51)

Age group

0–3 months

102 (27)

47 (31)

50 (28)

5 (9)

>

3 m–1 years

82 (22)

34 (23)

39 (23)

9 (11)

>

1–5 years

90 (24)

25 (17)

48 (28)

17 (30)

>

5–15 years

103 (27)

44 (29)

33 (19)

26 (46)

Weight for age

Normal (

>

0 SD)

80 (21)

36 (24)

34 (20)

10 (18)

0 to –3 SD

157 (42)

59 (39)

70 (41)

28 (49)

<

–3 SD

72 (19)

26 (17)

40 (24)

6 (11)

Unknown

68 (18)

29 (19)

26 (15)

13 (23)

*There were five patients with unknown gender, the rest were female (

n

=

184).