CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 32, No 2, March/April 2021

AFRICA

99

after initiating dialysis with a CVC (90 to 95%).

12,13

Factors

associated with improved outcomes in these countries include

early referral and a multidisciplinary approach.

14,15

Late referral,

conduit damage by venepuncture and a lack of secondary

intervention for failing fistulae contributes to high failure rates.

16

Another strategy proven to improve outcomes includes

pre-operative ultrasound to evaluate the size and quality of the

vein to be used.

6,17

A structured pre-dialysis care programme

allows the patient to be adequately prepared with counselling

and training, as well as early referral to the vascular access

surgeon.

17

Regular multidisciplinary meetings are useful to

refer new patients, discuss patients with early concerns about

access complications and deal with problematic vascular

access.

17

Having a dedicated vascular access co-ordinator with

a pre-operative ultrasound protocol was shown to be the most

important factor in improving haemodialysis access outcomes.

18

There is currently no database for vascular access in South

Africa, and high-quality data in low- and middle-income

countries are limited.

4

The South African Renal Registry was

the only active African registry until the establishment of the

African Renal Registry in 2015.

19

Unfortunately, they do not yet

record vascular access data. Having data in registries helps to

inform future planning, guides practice, assists in future research

and helps decide on resource allocation.

19

In order to improve

access utilisation in the haemodialysis population, one needs to

evaluate the current practice.

19

The aim of this study was therefore to examine the current

and past use of AVFs, AVGs and CVCs in our unit, in light of

national and international recommendations. This was done by

performing an audit of all patients enrolled in the haemodialysis

programme at our hospital. The objective was to identify any

factors preventing this unit from achieving guideline targets

and to propose changes that could be implemented to achieve a

better haemodialysis access service.

Methods

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Faculty of Health

Sciences Postgraduate Education, Training, Research and Ethics

Unit of the Walter Sisulu University.

We performed an audit on the vascular access for chronic

haemodialysis patients in Livingstone Tertiary Hospital in Port

Elizabeth, South Africa. A retrospective folder review was done

to identify demographic data and full vascular access history.

The data were used to calculate the time from commencement

of haemodialysis until the first attempt at the creation of a

permanent vascular access. Each modality of haemodialysis access

was then evaluated in the patient’s records. The date of insertion

or creation of each modality was recorded. Where available, the

complications associated with each were also recorded.

All patients enrolled in the haemodialysis programme at

Livingstone Hospital on 1 June 2018, who had adequate records,

were included in the study. Patients requiring temporary dialysis

or awaiting transfer to peritoneal dialysis were excluded.

Results

Sixty-six patients formed the study sample, with age ranging

from 21 to 67 years and a mean age of 44 years (95% CI:

42–46.8). Demographic details are shown in Table 1.

The majority of subjects [37 (56%)] were using a tunnelled

CVC as their permanent vascular access, an autogenous AVF was

used in 25 (38%) and an AVG in three (5%) patients. One patient

was using a temporary CVC while awaiting a more definitive

access modality (Table 2). Within the group that was using a

CVC as permanent access, three subgroups were identified: those

who had no AVF created or AVG inserted (12%), those with one

previous failed AVF or AVG (21%), and those who had had more

than one previous attempt at an AVF or AVG (23%).

Central venous catheters were used in 95% of the studied

patients as the initial modality. This included 38 patients (58%)

who started with a temporary CVC and 25 (38%) who started

with a tunnelled CVC. Only six (10%) patients had pre-emptive

creation of permanent access, of which three were successfully

used. The other three had a primary failure and had to have

dialysis initiated using a CVC (Table 2).

The timing from initiation of haemodialysis until the first

attempt at AVF creation was also investigated (Fig. 1). In total,

101 AVFs were created in the study group. The number of access

creation attempts and the complications experienced are shown

in Table 2. There was no recorded episode of significant dialysis

access-associated steal syndrome. The data were inadequate to

calculate primary and secondary patency rates.

Discussion

Despite the young age of this population receiving haemodialysis

in our unit, there was a high rate of CVC use and a very high

rate of serious complications, such as clinically apparent central

venous stenosis. The target for AVF use in any unit, as set by

the Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative, is 65%. Several high-

income countries are reporting AVF prevalence this high.

7

Only

38% of our study population were using an AVF. The high

rate of CVC use in this study is therefore not in keeping with

guideline recommendations. However, on further investigation,

it is clear that CVC use was not the primary strategy, since most

of these patients had had prior AVFs that failed.

While only 12% of the entire group had never had, or was

not then using an AVF, unfortunately 95% of the patients

started dialysis using a CVC, with only 5% having a successful

pre-emptive fistula. This reliance on CVCs increases the failure

rate of AVFs created in the future as prior CVC use decreases the

benefit of an AVF.

11

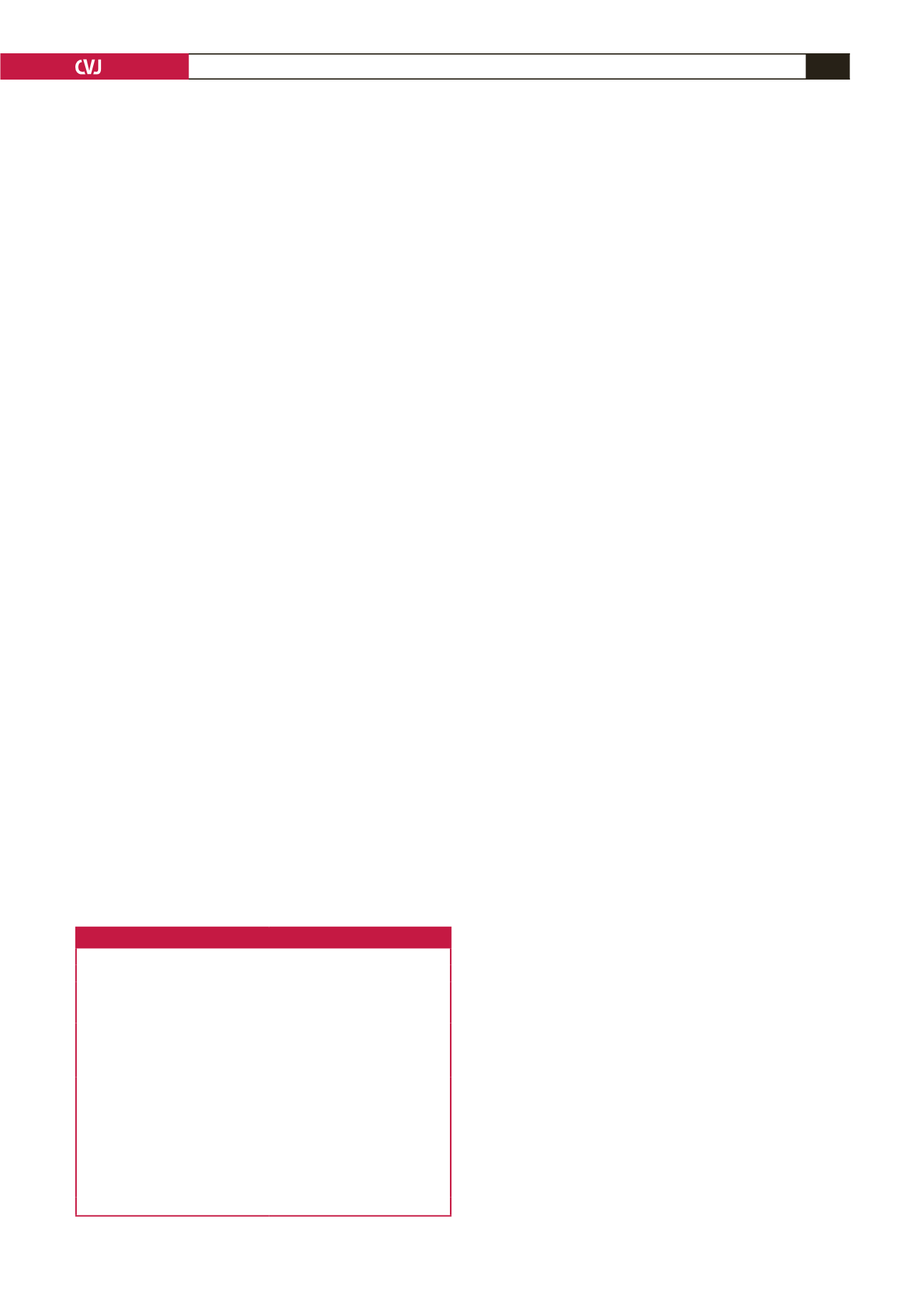

Table 1. Demographic data of the 66 patients

Demographics

Values

Mean age, years (95% CI)

44 (42–46.8)

Gender,

n

(%)

Male

Female

35 (53)

31 (47)

Race,

n

(%)

Black

Coloured

White

43 (65)

17 (23)

6 (9)

Aetiology of renal failure,

n

(%)

Hypertension

Unknown

Polycystic kidney disease

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Vesico–ureteric reflux

Sepsis

Glomerulonephritis

50 (76)

6 (9)

3 (5)

3 (5)

2 (3)

1 (2)

1 (2)

Mean BMI, kg/m² (95% CI)

24.4 (22.6–25.3)

BMI, body mass index.