CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 32, No 2, March/April 2021

100

AFRICA

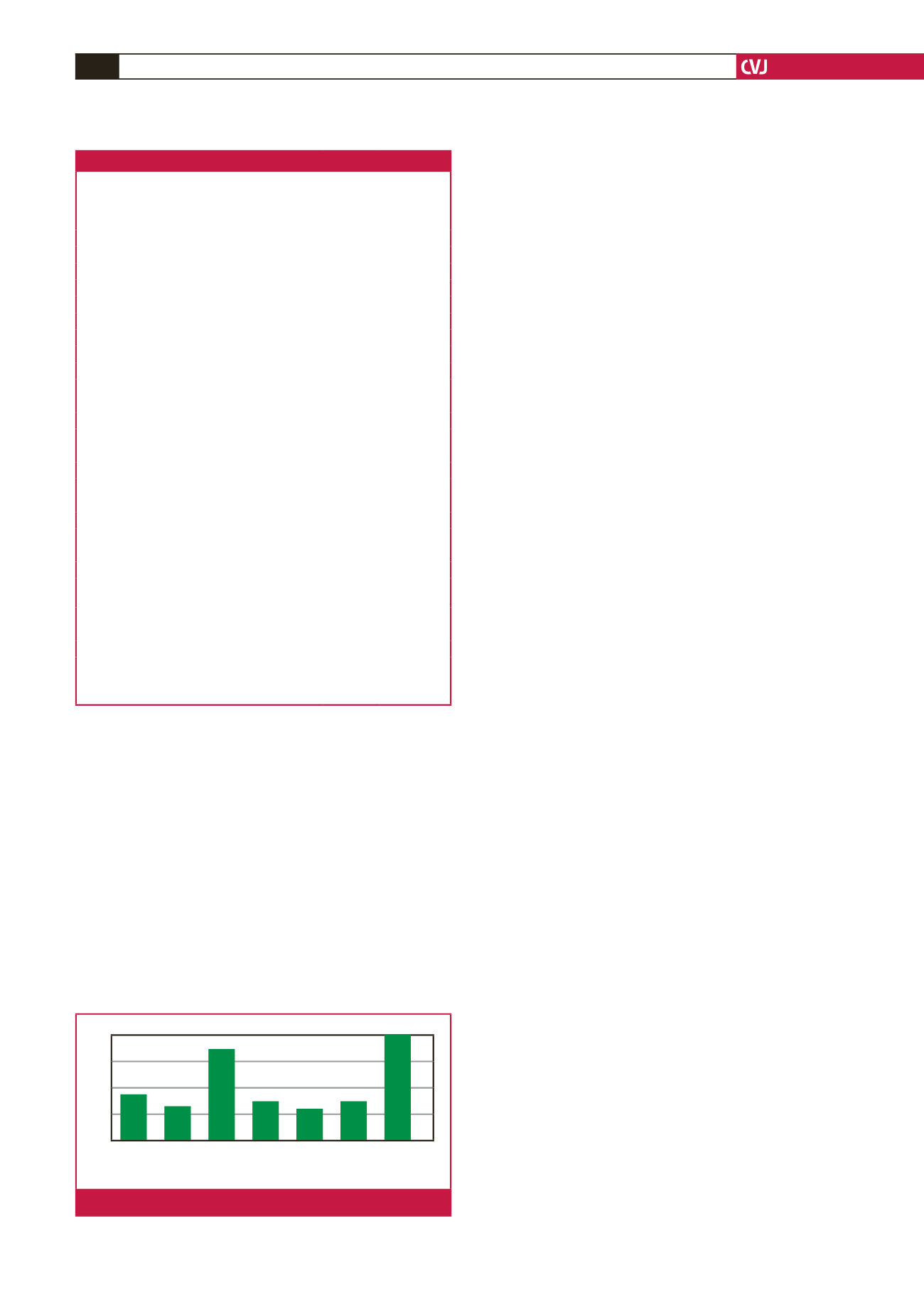

While late presentation with advanced kidney disease is a

common occurrence in our unit, necessitating the use of CVCs,

long delays to creation of permanent access after starting dialysis

prolongs exposure to the harmful effects of CVCs.

11,20

Almost a

third of patients in this study waited more than 12 months prior

to the first AVF attempt. This most likely contributed to the high

failure rate when an AVF was eventually created. Pre-emptive

fistulae should ideally be fashioned three to six months before

the first haemodialysis session to allow for maturation and

re-intervention if necessary.

5-7

These findings are similar to reports from sub-Saharan Africa

as well as other low- and middle-income countries, where most

patients will start dialysis on an emergency basis and cannot wait

for a fistula to mature.

16,21

This perpetuates the cycle, as higher

rates of CVC use lead to poorer outcomes with AVFs, which lead

to more CVC use. Except for the high primary failure rate, a lack

of secondary intervention also decreases the long-term patency

rates of the AVFs. Whenever failing fistulae are identified,

rapid referral for intervention prior to a complete occlusion is

required. Interventions done to maintain the fistula prior to

complete occlusion are more likely to be successful.

22

The access

surgeon also requires available theatre time to be able to attempt

salvage. When urgent secondary interventions are not available,

the fistulae will simply be abandoned when they occlude.

16

The documented complication rates may have been

underestimated in this retrospective study as it relied on the

adequacy of the patient records. Central venous stenosis or

occlusion was recorded in a quarter of the patients. This may

even be an underestimation, since patients are not routinely

screened for evidence of central venous obstruction and only

clinically apparent central venous obstruction was recorded. The

damage caused by long-term CVC use leads to central venous

stenosis and can compromise future access options.

23

Recommendations for improving current practice

Early detection of CKD and timely referral: many patients

present late with end-stage kidney disease. Ongoing education of

healthcare providers is needed to promote early referral. Early

detection of CKD may avoid the need for urgent dialysis and

therefore CVC use, allowing time for pre-emptive access creation.

24

Dedicated vascular access clinic: a specialisedmultidisciplinary

clinic should be formed that deals primarily with new and

problematic vascular access cases.

18

This multidisciplinary team

should include a vascular access surgeon, a nephrologist, dialysis

nursing staff and supporting staff. All new referrals can be seen

and access planning started prior to the first dialysis session.

Ultrasound evaluation can be done at the initial visit to map

out potential access sites and look for problematic areas such

as prior vein injury by cannulation. When there are concerns

regarding early AVF failure, intervention can then be planned

and the patient prioritised for surgical revision from this clinic.

In this format there will be open communication between the

different members of the haemodialysis team. It will also allow

time for patient education in a neutral environment with all the

different team members available.

Availability of a dedicated vascular access theatre list: without

access to theatre it would not be possible to run an effective

vascular access service. The best way to optimise the timing to

AVF creation and deal with failing fistulae or complications

would be to allocate a dedicated vascular access theatre list.

This list should ideally be in a hybrid theatre or a theatre

with fluoroscopy available so that both open surgical and

endovascular interventions can be performed as needed. The

haemodialysis patients can then be prioritised and would not

need to compete for theatre time with all the other emergency

and elective surgical patients.

A dedicated access co-ordinator: it would be valuable to

appoint a dedicated vascular access co-ordinator. This should

be a trained nurse experienced in haemodialysis and vascular

surgery. Ideally one of the experienced nurses currently in the

unit could fulfil this role. The co-ordinator will be the link

between the patient, dialysis staff, nephrologist and access

surgeon. This strategy has been shown to be very effective in

improving haemodialysis outcomes.

18

Table 2. History of vascular access creation and complications

History

Number

Percentage of

study

populations

Current access

Tunnelled CVC

37

56

AVF

25

38

AVG

3

5

Temporary CVC

1

2

CVC group sub-analysis

Patients using a CVC at present

37

56

With no previous AVG or AVF

8

12

With 1 previous AVG or AVF

14

21

With > 1 previous AVG or AVF

15

23

Initial vascular access

CVC

63

95

Non-tunnelled CVC

38

58

Tunnelled CVC

25

38

Pre-emptive AVF

3

5

Number of AVF or AVG attempts

No previous AVF or AVG

8

12

1 AVF or AVG

29

44

2 AVF or AVG

15

23

3 AVF or AVG

13

20

4 AVF or AVG

1

2

Complications

Central venous stenosis or occlusion (of 66

patients)

17

26

Aneurysmal dilatation (of 101 AVFs)

15

15

Aneurysmal and still in use (of 15)

9

60

Aneurysmal and abandoned (of 15)

6

40

Dialysis access-associated steal syndrome

0

0

CVC, central venous catheter; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous

graft.

18

14

9

5

0

Time to first AVF attempt in relation to starting haemodialysis (months)

No attempt Pre emptive 0–3 3–6 6–9 9–12

>

12

Fig. 1.

Time to first fistula attempt (months).