CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 26, No 2, March/April 2015

74

AFRICA

Bacterial infection is also hypothesised to play a minor

pathogenetic role. Although secondary infection caused by

bacteria, viruses and fungi have been implicated, this has not been

conclusively demonstrated. In the series by Nair

et al

.,

29

micro-

organisms were not identified, while in that of Marks and Kuskov,

28

Staphylococcus aureus

was isolated from peri-aneurysmal exudate.

It is debatable whether the latter was a surface contaminant.

Management

In the current era, HIV-infected patients presenting with vascular

pathology are managed by the standard guidelines of HIV-naïve

patients, with conservative management being reserved for

patients with full-blown AIDS.

3,4,26,47-49

The overall management

of these patients poses a moral and ethical dilemma with regard

to the appropriateness and timing of surgical intervention.

At present there are no universal guidelines. Emergencies are

prioritised irrespective of immune status. The majority of

patients are young, fit and able to tolerate major surgery.

Treatment should be individualised and priority given to

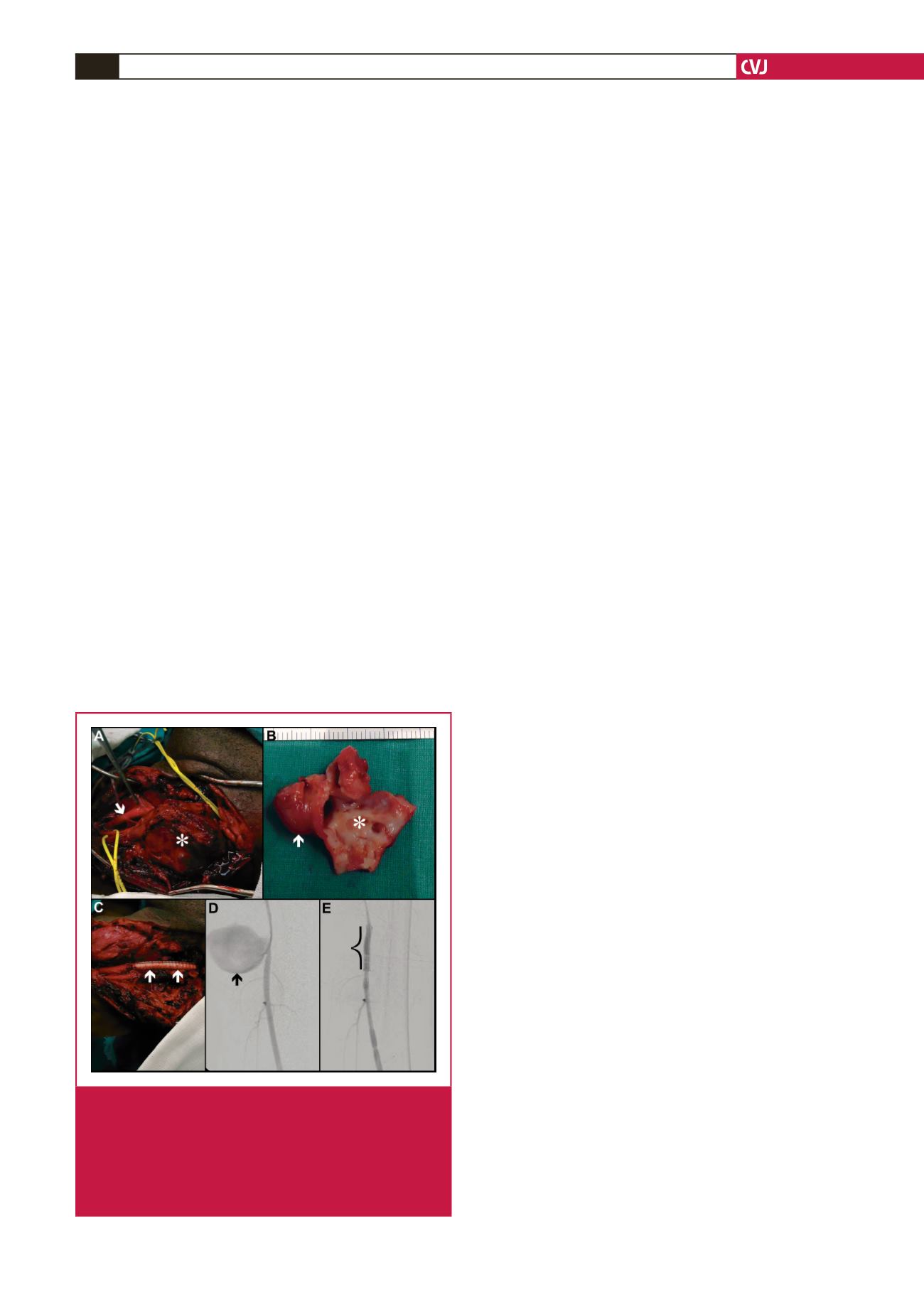

patients with symptomatic aneurysms. Intra-operatively, false

or true aneurysms are identified (Fig. 4A).

3,4,26

Intervention is

offered for symptomatic aneurysmal lesions, and involves either

ligation of vessels in septic lesions and occluded distal vessels, or

resection (Figs 4B) and restoration of arterial continuity (Fig.

4C) following aneurysmal excision.

3,4

The ligation of carotid

lesions seems to be well tolerated, as evidenced by Nair

et al

.,

29

with little or no neurological sequelae peri-operatively. The

choice of conduit, namely prosthetic or autogenous grafts, for

surgical bypass remains controversial.

29

The latter is plagued by

the associated risk of deep-vein thrombosis in these patients.

In selected patients with appropriate technical imaging criteria

and poor physiological reserves, endovascular management with

a stent-graft (Fig. 4D, E) constitutes a suitable alternative.

Anecdotal reports with small patient numbers have documented

its selected use and immediate success.

26,50,51

Complications of

this modality include stent-graft sepsis, occlusion, endoleaks and

missed opportunistic infections.

4,52

Scholtz

53

has raised concerns

about this modality, from a radiological perspective, with

regard to angiographic access, small-calibre vessels and contrast

pooling in the multiple aneurysms. Despite these reservations, it

remains an attractive alternative because it promotes flexibility

of treatment options. Endovascular intervention represents

technology in evolution, with unknown long-term results. Patient

selection is therefore crucial; the procedure should be reserved

for patients with poor physiological reserves.

There have been no comparative studies, to date, on

surgery versus endovascular intervention in patients with HIV

vasculopathy. Expertise in this sphere is at present anecdotal

and has been confined to isolated case reports.

54,55

From a

technical perspective, these aneurysms may present a challenge

in relation to their large size, vessel tortuosity, flow dynamics

and specific anatomical location, especially in relation to outflow

tracts that may originate in close proximity to, or from the

aneurysm sac itself. The branch vessels of interest in this instance

would include the vertebral, internal iliac and visceral arteries.

The rationale for endovascular intervention entails aneurysmal

exclusion of the target vessel and preservation of laminar flow

in the outflow tract. Endovascular devices to exclude these

aneurysms include the use of covered or uncovered stents in the

form of multi-layered compact cobalt,

55

or open-cell nitinol mesh

design. More recently, a novel idea of aneurysm exclusion using

multi-layered stent technology without compromising branch

vessel patency has been reported in HIV-infected patients.

The basis for this technique has been extrapolated from the

pipeline embolisation device,

54

which is used to treat intracranial

aneurysms. Its successful usage has been described by Euringer

et al.

55

in a patient with multiple HIV-related aneurysms. The

deployment of this type of stent achieves aneurysm exclusion

and restoration of laminar flow with aneurysm autothrombosis

as a result of strangulated flow.

This technique can, in theory, also be augmented with

coiling to ensure complete thrombosis within the aneurysm

sac. Success when utilising the multi-layered stent in this setting

requires definition because the aneurysmal sac can be completely

excluded with total sac content thrombosis or sac shrinkage

with sluggish flow. According to the authors,

55,56

the merit in this

technique facilitates continuous branch vessel patency, especially

the patency of visceral branches of the aorta. Sustained patency

may require the use of long-term antiplatelet therapeutic agents

such as clopidogrel. The effect of this type of anti-platelet

therapy may be negated by some anti-retroviral agents,

54

but it

is possible to identify patients with this form of resistance prior

to intervention.

The multi-layered stent has the technical limitations of a

compact strut design, which precludes additive coiling and

potential excessive foreshortening during deployment. This

may result in a geographical miss. Although the endovascular

approach is cushioned and not plagued by the physiological

challenges of robust anaesthesia, blood loss and the peri-operative

complications of contamination, wound sepsis and transfusion

Fig. 4.

HIV aneurysm management: intra-operative left

common carotid artery exposure (A, arrow) with

aneurysm (*). Resected specimen (B) with aneurysm

(arrow) and pseudo-aneurysm (*). Prosthetic inter-

positional graft (C, arrows). Endovascular manage-

ment of a left superficial femoral artery pseudo-aneu-

rysm (D, arrow) with a stent graft (E, bracket).