CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 27, No 2, March/April 2016

AFRICA

101

sense to patients, and it is incumbent on the clinician to take

the time to allay fears, ensuring good and clear communication

during counselling.

‘Safe’ is a relative term but one that physicians should not be

afraid to use. When a radiographic study is needed for appropriate

management of a pregnant patient, the ACR recommends that

‘health care workers should tell patients that X-rays are safe and

provide patients with a clear explanation of the benefits of X-ray

examinations.’

74

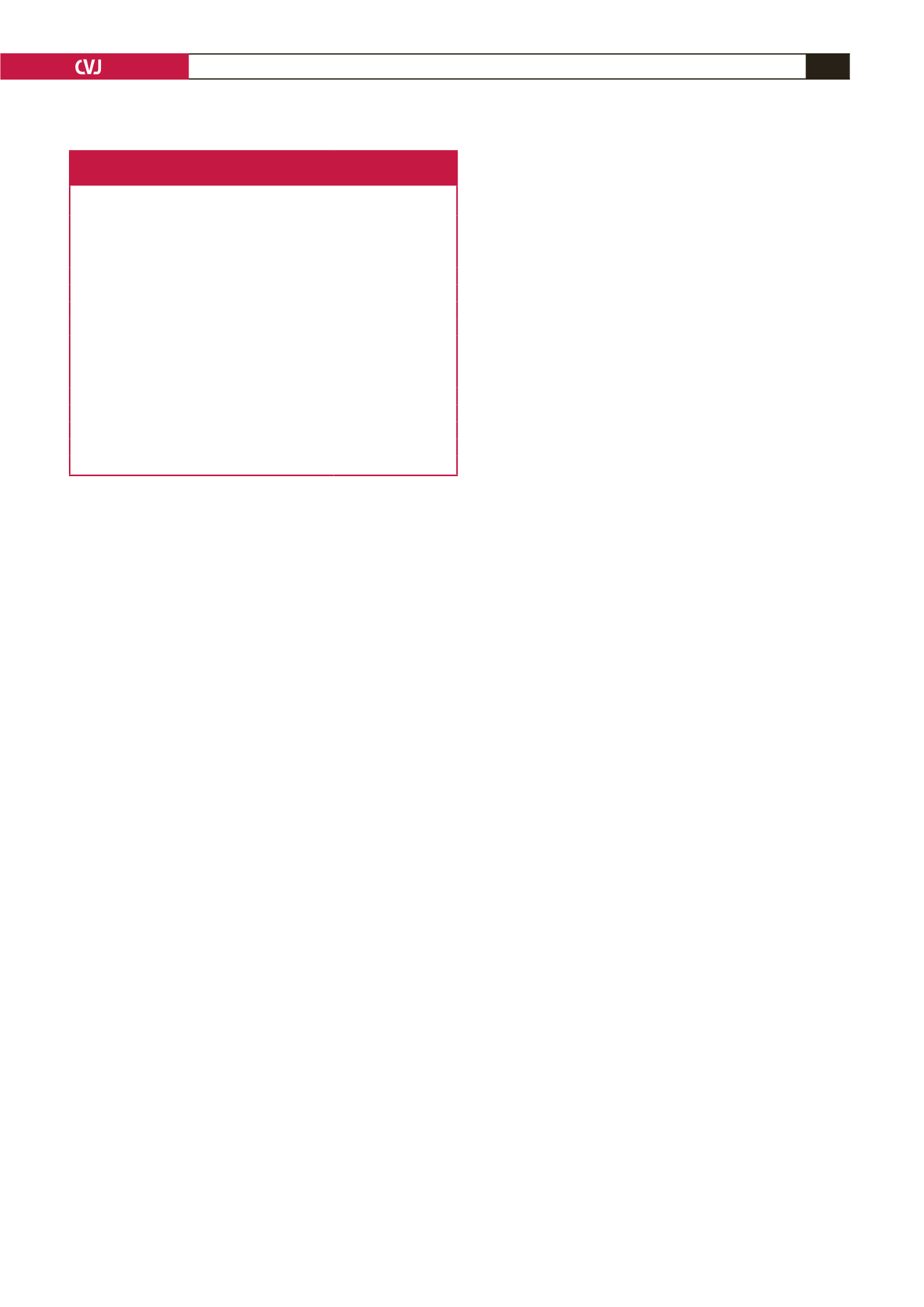

One tool that physicians may consider using

to reassure patients is Table 3, which compares the dosage of

radiation provided by various common diagnostic studies with

the accepted limit of 5 rad (50 mSv). A patient’s particular study

could also be plotted on this graph, showing the clear margin of

safety that exists for all single diagnostic studies.

Conclusion

Pregnant women with known or suspected CVD often require

cardiovascular imaging. The accepted maximum limit of ionising

radiation exposure to the foetus during pregnancy is a cumulative

dose of 5 rad (50 mSv or 50 mGy). Concerns related to imaging

modalities that involve ionising radiation include teratogenesis,

mutagenesis and childhood malignancy. Importantly, no single

imaging study approaches this cautionary dose of 5 rad (Table

4). Elective studies may be deferred until the pregnancy is over

or the gestational period is beyond 20 weeks, and there are

several strategies that may be employed to minimise radiation

to the foetus (Table 3). Echocardiography and CMR appear

to be completely safe in pregnancy and are not associated with

any adverse foetal effects, provided there are no general contra-

indications to MR imaging. Current evidence suggests that a

single cardiovascular radiological study during pregnancy is safe

and should be undertaken at all times when clinically justified.

As a general guide, centres where medical imaging is

performed should have signs to remind mothers to notify the

staff if they may be pregnant. The potential risks of each

imaging modality must be discussed with the mother before

she undergoes such imaging. Pregnant women must be made

to understand that exposure from a single diagnostic procedure

does not result in harmful foetal effects. Specifically, exposure

to less than 5 rad has not been associated with an increase in

foetal anomalies or pregnancy loss. Therefore concerns about

possible effects of high-dose ionising radiation exposure should

not prevent medically indicated diagnostic X-ray procedures

from being performed on pregnant women. Consultation with

an expert in dosimetry calculation may be helpful in calculating

estimated foetal dose when multiple diagnostic X-ray procedures

are performed in pregnancy.

In general, the radiation safety principle, ALARA (as low

as reasonably achievable), minimising radiation and release

of radioactive materials should be employed at all times. In

addition, the use of iodine-based contrast agents for X-ray,

fluoroscopy and CT scanning, and the use of gadolinium-based

contrast agents for CMR are safe in pregnancy and should be

used when the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to

the foetus. However, the use of radioactive isotopes of iodine is

contra-indicated for therapeutic use during pregnancy.

Dr Ntusi acknowledges support from the National Research Foundation and

Medical Research Council of South Africa.

References

1.

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion.

Number 299, September 2004 (replaces No. 158, September 1995).

Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy.

Obstet Gynecol

2004;

104

(3): 647–651.

2.

Hall EJ. Scientific view of low-level radiation risks.

Radiographics

1991;

11

(3): 509–518.

3.

Brent RL. Utilization of developmental basic science principles in the

evaluation of reproductive risks from pre- and postconception environ-

mental radiation exposure.

Teratology

1999;

59

: 182-204.

4.

International Commission on Radiological Protection. Pregnancy

and medical radiation.

Annals of the International Commission on

Radiological Protection.

Oxford: Pergamon Press, 2000, Publication 84.

5.

Gray JE. Safety (risk) of diagnostic radiology exposures. In:

American

College of Radiology. Radiation Risk: a Primer

. Reston (VA): ACR’

1996: 15–17.

6.

Brent RL. The effect of embryonic and fetal exposure to X-ray, micro-

waves, and ultrasound: counseling the pregnant and nonpregnant

patient about these risks.

Semin Oncol

1989;

16

: 347–68.

7.

Parry RA, Glaze SA, Archer BR. The AAPM/RSNA physics tutorial

for residents. Typical patient radiation doses in diagnostic radiology.

Radiographics

1999;

19

: 1289–1302.

8.

Wieseler KM, Bhargava P, Kanal KM, Vaidya S, Stewart BK, Dighe

MK. Imaging in pregnant patients: examination appropriateness.

Radiographics

2010;

30

(5): 1215–1233.

9.

Streffer C, Shore R, Konermann G,

et al

. Biological effects after

prenatal irradiation (embryo and fetus). A report of the International

Commission on Radiological Protection.

Ann Int Comm Radiol Protect

2003;

33

(1–2): 5–206.

10. McCollough CH, Shueuler BA, Atwell TD, Braun NN, Renger DM,

Brown DL,

et al

. Radiation exposure and pregnancy: should we be

concerned?

Radiographics

2007;

27

: 909–918.

11. Toppenberg KS, Hill DA, Miller DP. Safety of radiographic imaging

during pregnancy.

Am Fam Physician

1999;

59

(7): 1813–1818.

12. Loganovsky K. Do low doses of ionising radiation affect the human

brain?

Data Science J

2009;

8

: 13–35.

13. Wagner LK, Lester RG, Saldana LR.

Exposure of the Pregnant Patient

to Diagnostic Radiations: a Guide to Medical Management.

Madison,

USA: Medical Physics Publishing, 1997.

Table 4. Doses to the foetus from radiological and

nuclear medicine examinations

Examination

Estimated foetal dose

(mGy)

Chest radiograph

< 0.0001

Pulmonary CTA

0.01–0.66

CCTA (prospective gating)

1.0

CCTA (retrospective gating)

3.0

Abdominopelvic CTA

6.7–56.0

Direct fluoroscopy (groin to heart catheter passage) 0.094–0.244 mGy/min

Coronary angiography

0.074

Electrophysiological procedures

0.0023–0.012 mGy/min

Lung perfusion

0.6

Lung ventilation

0.005–0.09

Myocardial perfusion

5.3–17

Gated blood pool

6.0

PET viability

6.3–8.1

PET perfusion

2.0

Maximum recommended dose

5 rad or 50 mGy