CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 4, July/August 2017

AFRICA

255

general hospital to which referrals can be made, while each

general hospital or secondary centre should be attached to a

tertiary centre or teaching hospital. Furthermore, there should

be annual reports for each primary and comprehensive health

centre, and performance should be rewarded.

Finally, governments should take the lead and involve the

private sector, non-governmental organisations and academia.

Such projects require constant funding and support.

Conclusion

The high burden of CVD and diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan

Africa means that individual governments must develop strategic

plans to equip their primary care clinics with well-trained

non-physician healthcare workers and basic instruments, such

as blood pressure apparatus, kits for urinalysis, and blood

glucose and cholesterol checks if an epidemic of chronic

non-communicable diseases is to be averted on the sub-continent.

Governments should also set up a referral system whereby there

is supervision and referral from primary care to secondary

centres, and two to five primary care centres should be attached

to a secondary centre.

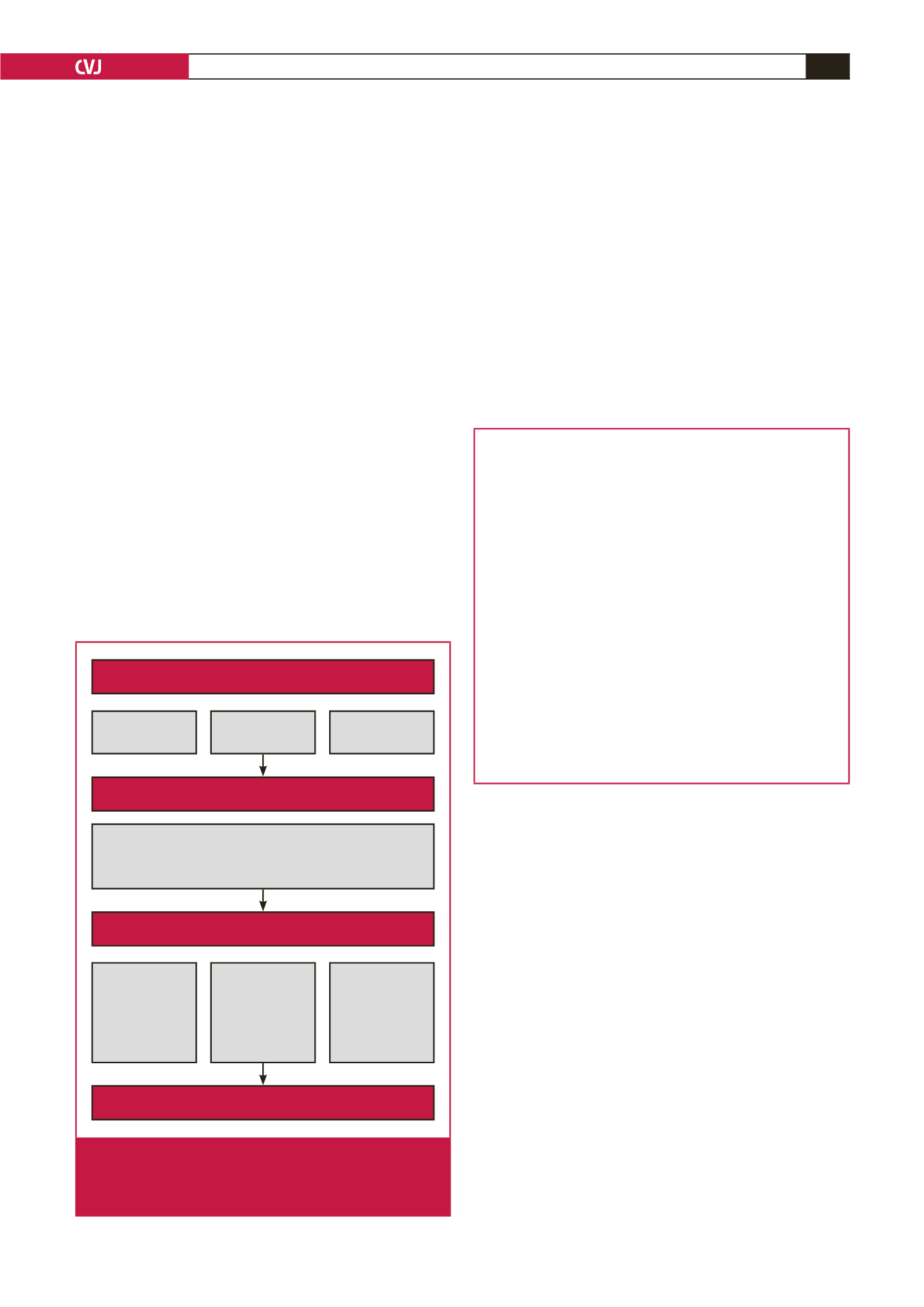

The Seychelles experience shows that the key drivers of

effective primary care to yield population-level impacts on

diabetes mellitus and CVD include research, a non-physician-

based approach, and integration of the media, the general

population, academia and non-governmental organisations. For

such a programme to succeed there must be a holistic framework,

developed by the government and coordinated by the NCD unit

of the federal ministry of health, as shown in Fig. 1. It should

involve research on CVD and diabetes, structured training of

non-physician healthcare workers, appropriate equipping of

primary healthcare centres and correct referral systems from

primary to secondary centres.

Limited resources were a disadvantage in the Seychelles

programme and would also be in sub-Saharan Africa. This

could be overcome with the support of non-governmental

agencies and the private sector, however, they would invest in

such programmes only if they had confidence in the government

of the country.

Key points

•

CVD plays a leading role in the disease spectrum of sub-

Saharan Africa, with stroke and ischaemic heart disease

ranked as seventh and 14th leading causes of death,

respectively, on this sub-continent.

•

Limited resources and the high cost of CVD treatment

necessitate that primary prevention should have a high

priority for CVD control in sub-Saharan Africa.

•

For any CVD intervention programme to succeed on the

sub-continent, a community-orientated approach must

be taken, especially in rural areas where transportation

is difficult, deterring people from seeking medical help at

urban and semi-urban health facilities.

•

Primary health centres therefore need to be equipped

with trained non-physician personnel who are supervised

by physicians, and also with basic tools such as blood

pressure apparatus, glucometers, urinalysis strips and

point-of-care machines for cholesterol checks.

This project was supported by award number D43TW008330 from the

Fogarty International Centre. The content is solely the responsibility of

the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the

Fogarty International Centre or the National Institute of Health. Dr

Dike Ojji is currently a Research Fellow at the Soweto Cardiovascular

Research Unit, University of Witwatersrand, South Africa under the Wits

Non-Communicable Disease Research Leadership Programme, funded by

the NIH (Fogarty) training programme. Dr Kim Lamont was funded by the

NRF scarce skills award.

References

1.

Murray CJL, Global Burden of Disease study group 2010. Disability-

adjusted life years (DALYS) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions,

1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study

2010.

Lancet

2012;

380

: 2197–2223.

2.

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of

disease from 2002 to 2030.

PLoS Med

2006;

3

(11); e442.

3.

Opie LH, Mayosi BM. Cardiovascular disease in sub-Saharan Africa.

Circulation

2005;

112

: 3536–3540.

4.

Expert Committee on Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease. WHO

Technical Report Series No 678. World Health Organization, Geneva,

1982.

Functional organisation of PHC services

Prerequisite

Enabling work environment and proper supervision

Supermarket

approach

• The size and structural set up of the clinic

• The availability and competency of nurses

• Availibity of equipment and space

PHC team

PARC:

P

roductivity,

A

vailability,

R

esponsibility,

C

ompetence

Comprehensive

healthcare

Organisational

support

SITE:

S

pace,

I

nfastructure,

T

ransport,

E

quipment

One-stop shop

Collaboration

PHC team,

C

ommunity,

NGOs,

Academia

Determinants

Fig. 1.

Organisational structure showing how primary health-

care can be effective in preventing cardiovascular

disease. PHC = primary healthcare. NGOs = non-

governmental organisations.