CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 6, November/December 2017

AFRICA

371

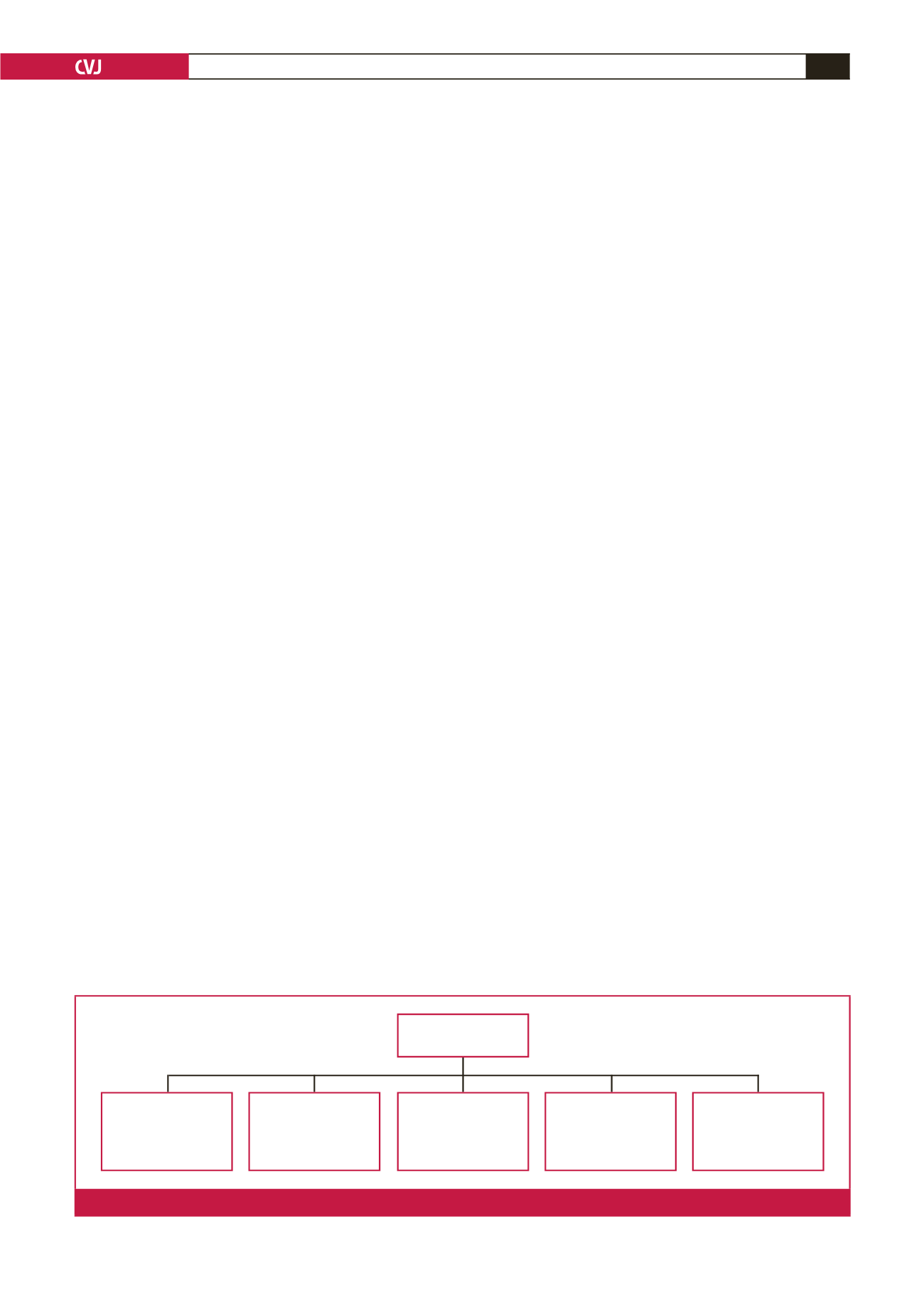

(PAH), venous, hypoxic, thromboembolic and miscellaneous

3

(Fig. 1). Overall, PH results from varying combinations of

increases in pulmonary vascular resistance, pulmonary blood

flow and pulmonary venous pressure. Sustained pressure

overload secondary to chronic PH leads to right ventricular (RV)

changes, including hypertrophy, dilatation and RV failure, which

are detectable using non-invasive tests such as electrocardiogram

(ECG), echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance or at best,

the gold standard but invasive right heart catheterisation (RHC).

Despite improvements in the understanding of PH and the

development of novel therapies, the condition is still diagnosed

at an advanced stage in a significant proportion of patients, due

to the paucity of symptoms in the early stages of the disease. This

has a negative impact on the quality of life and survival rate of

patients.

4

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart

Association

5

and the European Society of Cardiology/European

Respiratory Society

4

guidelines recommend the ECG as an initial

tool in diagnosing patients with suspected PH, based on studies

done predominantly in patients with PAH. However, these

guidelines consider ECG to be an inadequate tool for screening

and emphasise the advantage of Doppler echocardiography.

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where chronic and endemic

precursors of PH, including chronic infectious diseases,

hypertensive heart disease, cardiomyopathy and rheumatic heart

disease are highly prevalent,

6

early diagnosis of PH is of particular

relevance. The high cost and low availability of, and need for

expertise in echocardiography limit its utility in this part of the

world and justify the interest in alternative tests such as ECG.

ECG abnormalities in patients with PH have been

predominantly described in other populations.

7-11

The

Pan-African Pulmonary Hypertension Cohort (PAPUCO) was

established to map out the epidemiology of PH in SSA. In

this sub-study, we aimed to assess the predictive value of an

affordable, widely available, objective and reproducible test such

as ECG to diagnose PH in resource-limited settings.

Methods

As previously described,

12

the PAPUCO study was a prospective,

registry-type cohort study of PH in Africa. The registry aimed

to recruit consecutive patients with newly diagnosed PH based

on clinical and echocardiographic criteria, who would be able or

likely to return for a six-month follow up, who were at least 18

years old (except for those in paediatric centres in Mozambique

and Nigeria), and who consented in writing to participate in the

registry.

Centre eligibility included availability of echocardiography,

training in assessing right heart function, experience in

diagnosing PH according to the WHO classification, experience

in clinical management of patients with right heart failure

(RHF), and resources to review patients at six-month follow up.

Participating centres were invited to join the registry at African

cardiac meetings and conferences.

12

The Heart of Soweto study

was a study of 387 urban South Africans of predominantly

African descent, determined to be heart disease free (using the

Minnesota code) following advanced cardiological assessment,

including echocardiography.

13

PH was diagnosed by specialist cardiologists using the

non-invasive definition of PH. The standard is a pathological

condition with an increase in mean pulmonary arterial pressure

(PAP) beyond 25 mmHg at rest, as assessed by RHC.

14

Because

RHC is seldom available in our setting, PH was diagnosed

in patients with a documented elevation in right ventricular

systolic pressure (RVSP) above 35 mmHg on transthoracic

echocardiography in the absence of pulmonary stenosis and

acute RHF, usually accompanied by shortness of breath, fatigue,

peripheral oedema and other cardiovascular symptoms, and

possibly ECG and chest X-ray changes in keeping with PH,

as per the European Society of Cardiology and European

Respiratory Society (ESC/ERS) guidelines on PH.

4

We searched ECGs from the PAPUCO registry to identify all

patients who had had bothDoppler echocardiography and 12-lead

ECG performed within 48 hours of their baseline inclusion. We

excluded all patients with pacemakers (due to inapplicability of

standard ECG criteria), poor-quality ECGs and those without

measurable RVSP. Controls were non-smokers and asymptomatic

subjects with normal Doppler echocardiography (and RVSP less

than 35 mmHg) who all underwent ECG recordings during their

baseline inclusion in the Heart of Soweto study.

15

This study

represents urban South African men and women, all free of any

heart disease and other major forms of cardiovascular disease.

All ECGs were reviewed and interpreted by two independent

clinical cardiologists who were blinded to the echocardiography

results. If consensus could not be reached, a third opinion (AD,

FT or KS) was requested. We electively studied pre-specified

ECG patterns classified into minor or major abnormalities, as

previously described in a large African cohort of heart disease-free

Africans.

13

Minor abnormalities included sinus tachycardia (

>

100

beats per min), minor T-wave changes (T-wave flattening) or early

repolarisation, definitive right ventricular hypertrophy (QRS axis

≥

+

100° or R/S ratio in V1

≥

1, or R in V1

>

7 mm or a combination

of a right bundle branch block and QRS axis

≥ +

100°).

Pulmonary

hypertension (PH)

Group 3: PH due to

lung diseases and/or

hypoxaemia

e.g. chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease

Group 4: Chronic

thromboembolic CPH

e.g. chronic pulmonary

embolism

Group 5: PH with

unclear or multifactorial

mechanisms

e.g. endomyocardial

fibrosis

Group 2: PH due to left

heart disease

e.g. mitral stenosis

due to rheumatic heart

disease

Group 1: Pulmonary arte-

rial hypertension (PAH)

e.g. human immuno-

deficiency virus-

associated PAH

Fig. 1.

World Health Organisation classification for PH adapted from the 5th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension.

3