CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 23, No 4, May 2012

208

AFRICA

postoperative improvement and was discharged but he

represented three months later with worsening of pre-operative

symptoms. He then had a pericardiectomy, following which he

improved progressively.

Following tube pericardiostomy, DS had very transient

improvement in his symptoms. Repeat lateral chest X-ray showed

evidence of pericardial calcification while echocardiography

showed moderate pericardial effusion and diastolic dysfunction

(Fig. 4). He made a rapid recovery following pericardiectomy.

MNhadminimal improvement following tubepericardiostomy,

remaining dyspnoeic at rest. Postoperative chest radiography

and echocardiography showed pericardial calcification. In

addition, there was a markedly enlarged right atrium, grade

III–IV tricuspid regurgitation and a small right ventricle with

endocardial thickening, suggestive of endomyocardial fibrosis.

We elected to go ahead with a pericardiectomy on account of

the pericardial thickening with calcification. She improved

following pericardiectomy, with NYHA class I status.

OS had pericardiostomy with slight improvement and

was discharged home on anti-tuberculous therapy. He had a

pericardiectomy three months later, during which he had an intra-

operative complication of right ventricular wall injury, which

was promptly repaired. He had an uneventful postoperative

recovery until the 12th and 19th days postoperatively, when

he developed Fournier’s gangrene and upper gastrointestinal

bleeding, respectively. These were successfully managed and he

was discharged home on the 36th day postoperatively.

Discussion

Effusive–constrictive pericarditis is said to be an uncommon

pericardial syndrome.

2

In a prospective study of 1 184 patients

with pericarditis, Sagrista-Sauleda

et al

. reported a prevalence of

only 1.3% among patients with pericardial disease of any type

(15/1 184) and 6.9% among patients with clinical tamponade

(15/218).

3

However, a recent observational study by Mayosi

et al

. reported 28 (15.1%) of 185 patients with tuberculous

pericarditis as belonging to that subset.

4

This is quite similar to

the prevalence of 13% among patients with pericardial disease

of any type in our seven-year review (11/86). We are not aware

of any specific series from Africa.

Patients with effusive–constrictive pericarditis present with

symptoms due to limitation of diastolic filling. These findings

are secondary not only to the pericardial effusion but also

the pericardial constriction. Symptoms and physical findings

vary, while a moderate-to-large pericardial effusion may occur.

Management of effusive–constrictive pericarditis is therefore

fraught with challenges.

The diagnosis is usually made by echocardiography, which

should demonstrate diastolic dysfunction. The diagnosis can

easily be missed by an unwary clinician because of the usual

superimposed features of accompanying pericardial effusion

or tamponade. This may have accounted for the premature

discharge and re-admission of one of our patients (SB).

Pericardial effusion is seen as an echo-free space around

the heart on echocardiography (Fig. 4). The presence of a

large pericardial effusion with frond-like projections and a

thick ‘porridge-like’ exudate is suggestive of an exudate but

not specific for a tuberculous aetiology.

1

Patients with acute

haemorrhagic effusions may have pericardial thrombus appearing

as an echo-dense mass.

5

Small pericardial effusions are only seen posteriorly, while

those large enough to produce cardiac tamponade are usually

circumferential. In large pericardial effusions, the heart may

move freely within the pericardial cavity (‘swinging heart’). In

the parasternal long-axis view, pericardial fluid reflects at the

posterior atrio-ventricular groove, while pleural fluid continues

under the left atrium, posterior to the descending aorta. Rarely,

tumour masses are found within or adjacent to the pericardium

and may masquerade as tamponade.

6

Diagnostic criteria for cardiac tamponade include diastolic

collapse of the right atrial and ventricular anterior free wall, and

left atrial and very rarely left ventricular collapse. Right atrial

collapse is more sensitive for tamponade, but right ventricular

collapse lasting more than one-third of diastole is a more

specific finding for cardiac tamponade. Doppler findings include

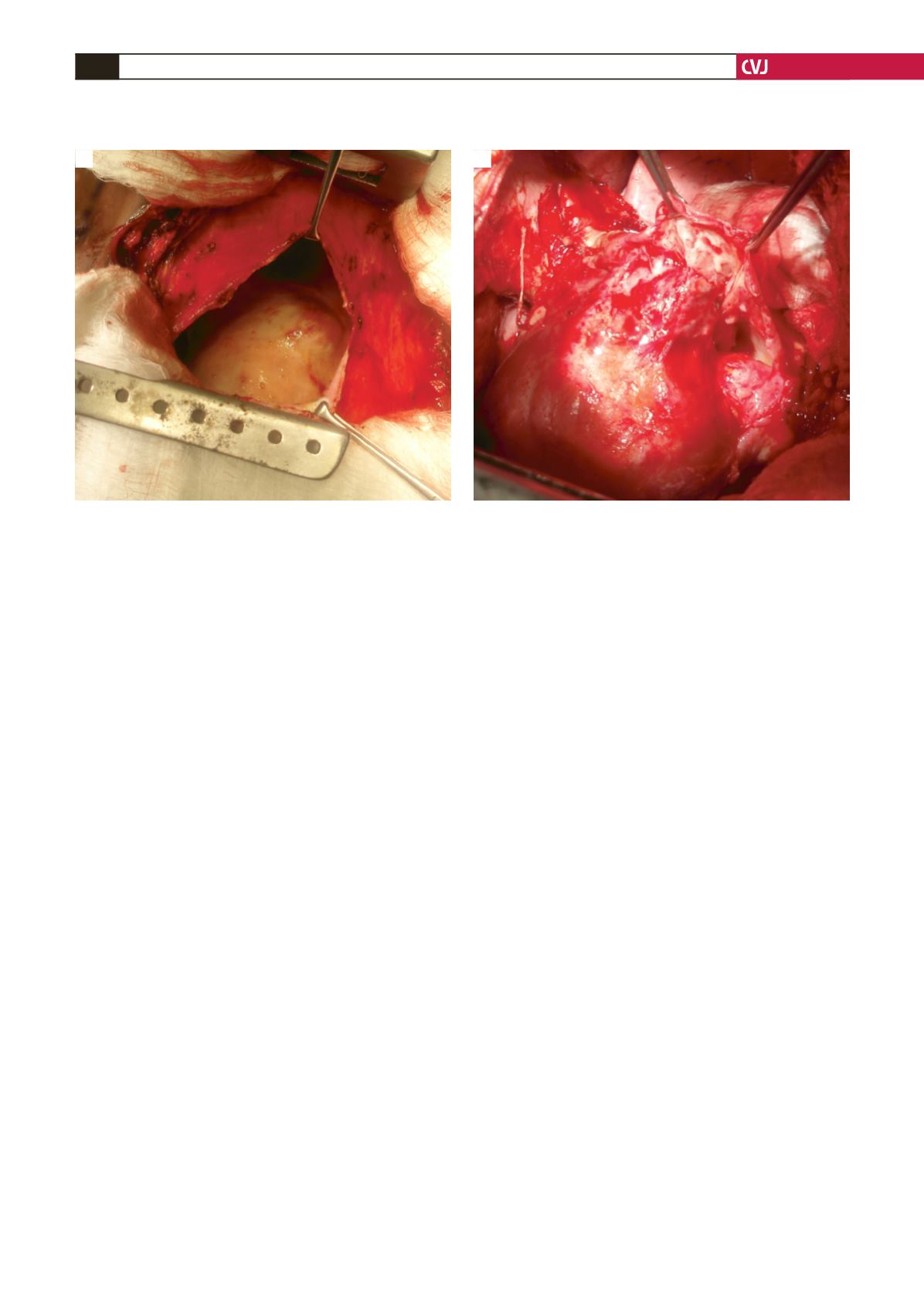

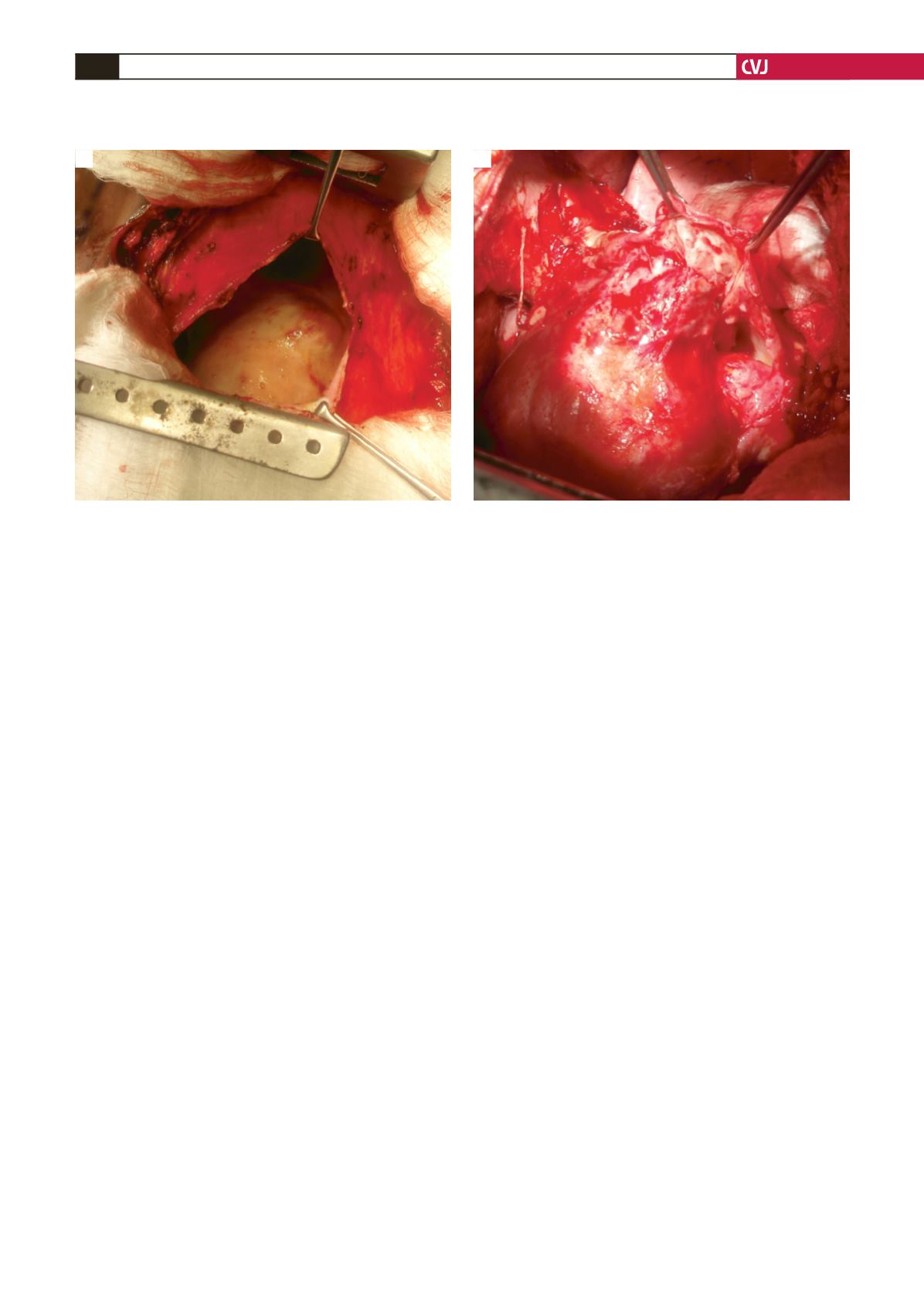

Fig. 3. (A) Thickened pericardium and a large pericardial space. (B) Final phase of visceral pericardial stripping.

A

B