CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 23, No 4, May 2012

210

AFRICA

pericardial exudate with elevated biomarkers of tuberculous

infection, and/or appropriate response to a trial of anti-

tuberculosis chemotherapy.

The diagnostic difficulty is best demonstrated by a recent

series of patients with tuberculous pericarditis where most

patients were treated on clinical grounds, with microbiological

evidence of tuberculosis obtained in only 13 (7.0%) patients.

4

Hence, the focus currently is on indirect tests for tuberculous

infection, including ADA levels and more importantly, lysozyme

or IFN-

γ

assay, which appears to hold promise for reaching

diagnosis of cases arising secondary to tuberculosis.

14-18

Technical

and financial constraints may, however, limit the diagnostic

utility of IFN-

γ

in many developing countries.

1

These tests are

currently not available in our centre.

The importance of recognising the haemodynamic syndrome

of tamponade and constriction characteristic of effusive–

constrictive pericarditis lies in an acknowledgment of the

contribution of the visceral layer of the pericardium to the

pathogenesis of constriction and of the need to remove it surgically.

However, not only is it sometimes surgically challenging to do

an epicardectomy in some patients due to a flimsy, fibrinous

visceral pericardium with attendant risk of haemorrhage; some

patients may recover with medical treatment alone – so-called

transient effusive–constrictive pericarditis.

3,19

Three of the

patients in this series actually had intra-operative haemorrhage

from atrial or ventricular injury during the epicardectomy part

of the procedure.

Visceral pericardiectomy is therefore a much more difficult

and hazardous procedure than parietal pericardiectomy, but

it is necessary for a good clinical result in cases of effusive–

constrictive pericarditis. The clinical decision as to which

patients need to be observed on medical treatment depends on

presumed or confirmed aetiology, timing of presentation, and

response to medical therapy.

Decision based on aetiology

Causes of effusive–constrictive pericarditis are varied and

usually practice-dependent. Tuberculosis is said to be responsible

for approximately 70% of cases of large pericardial effusion and

most cases of constrictive pericarditis in developing countries.

However, in industrialised countries, tuberculosis accounts for

only 4% of cases of pericardial effusion and an even smaller

proportion of instances of constrictive pericarditis.

14

Series from

Europe and North America report a predominance of idiopathic

cases, followed by cases that occur after radiotherapy or cardiac

surgery, or as a result of neoplasia or tuberculosis.

3,11,20

The aetiological spectrum indeed reflects the general

aetiological spectrum of pericardial diseases in each area

and can be influenced by the changing aetiological spectrum

of pericarditis in general and constrictive pericarditis in

particular.

3,21,22

The varying aetiological spectrum impacts on the

need for and timing of pericardiectomy.

17

In the Sagrista-Sauleda series, pericardiectomy was not

performed in eight of 15 patients; in five of them owing to a poor

general prognosis (four patients with neoplastic pericarditis)

or a high surgical risk (one patient with radiation pericarditis),

and in three patients (all with idiopathic pericarditis) because

of progressive improvement and eventually resolution of the

illness after pericardiocentesis. Wide anterior pericardiectomy

was performed in seven patients between 13 days and four

months after pericardiocentesis owing to the persistence of

severe right heart failure. The diagnoses in these seven patients

were idiopathic pericarditis in four, radiation pericarditis in one,

tuberculous pericarditis in one, and postsurgical pericarditis in

one.

The patients in our limited series, as in others cases due to

tuberculosis, usually had attendant pericardial calcification with

no room for improvement without pericardectomy. This partly

explains the need for pericardectomy in these patients.

Decision based on timing of presentation and

response to medication

Related to aetiology is the timing of presentation. Transient

sub-acute effusive–constrictive pericarditis is known to resolve

after pericardiocentesis without the need for pericardiectomy.

3,23,24

In fact in two of three patients with idiopathic pericarditis who

had resolution of their symptoms following pericardiocentesis in

the Sagrista-Sauleda series, the onset of their illness was stated

to be very recent. The monitoring of intra-cardiac and intra-

pericardial pressures as part of a pericardiocentesis procedure

has been suggested in patients who present with a sub-acute

course of pericardial tamponade, particularly those in whom the

condition is idiopathic or is related to infection, neoplasm or

rheumatological disease.

2

The duration of pericardial disease in three of our patients

was more than two years, suggesting chronicity and need for

pericardectomy. Although the duration in the fourth and fifth

patients was relatively short, non-resolution of their symptoms

and presence of pericardial calcification in the fourth patient

appeared to be a predictor of need for pericardial stripping.

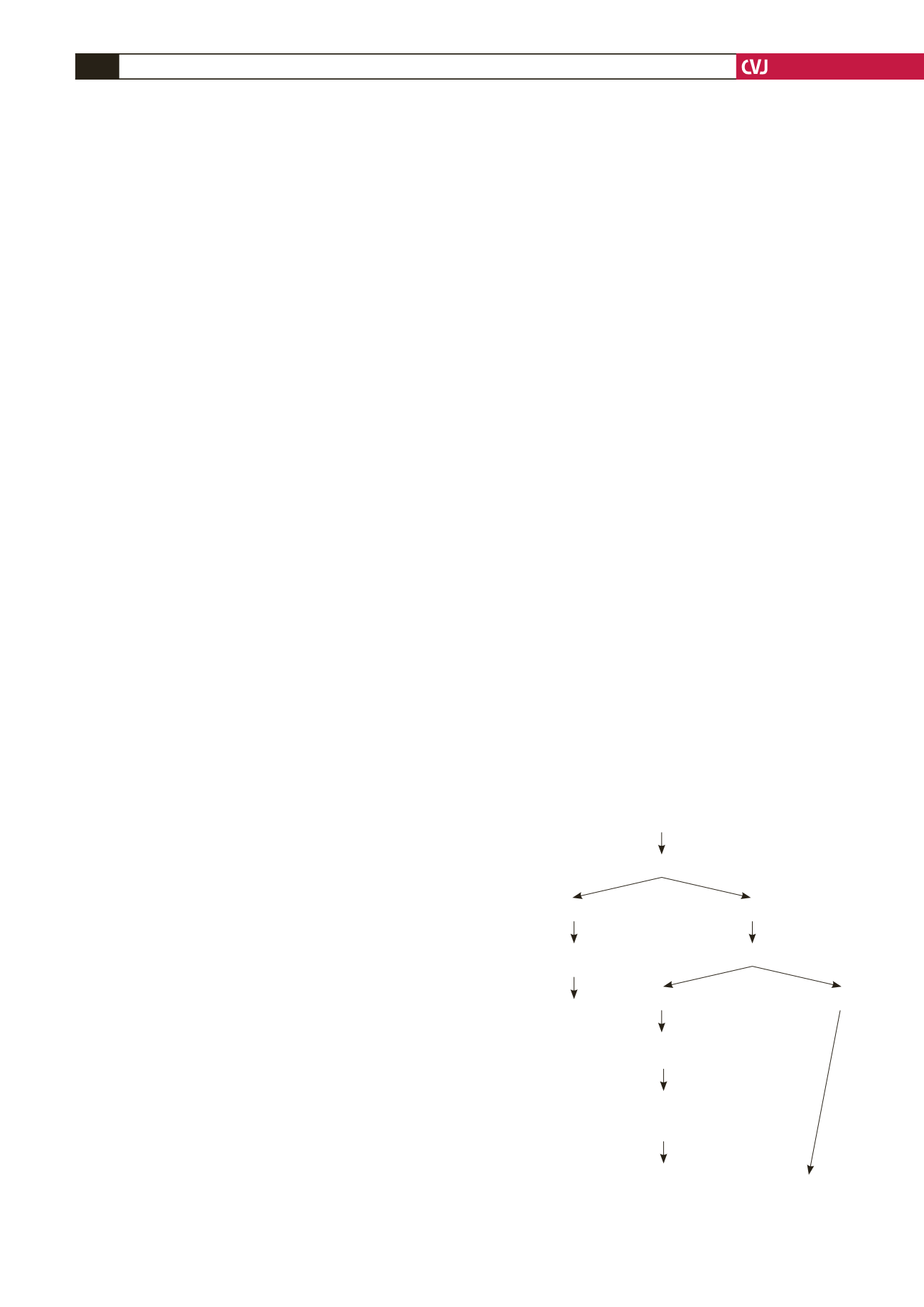

Fig. 5. Potential algorithm for the management of effu-

sive–constrictive pericarditis.

Effusive–constrictive pericarditis diagnosed?

• Based on radiological finding of cardiomegaly

• Evidence of constrictive physiology on echocardiography

Clinical or echo findings of tamponade?

No

Pericardiostomy +

pericardial biopsy

Duration less than 1 year

Yes

No

Medical treatment +/–

pericardiocentesis

Tuberculous/calcification/

persistent symptoms/

elevated venous pressures

Pericardiectomy including visceral pericardium

Yes