CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 23, No 4, May 2012

AFRICA

209

distension of the inferior vena cava that does not diminish with

inspiration, which is a manifestation of the elevated venous

pressure in tamponade.

6

In addition, there can be marked

reciprocal respiratory variation in mitral and tricuspid flow

velocities. Tricuspid flow increases and mitral flow decreases

during inspiration (the reverse in expiration).

Achallengingdifferentialdiagnosisisendomyocardialfibrosis,

a common form of restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) in Africa.

7

Because constrictive pericarditis can be corrected surgically, it

is important to distinguish chronic constrictive pericarditis from

restrictive cardiomyopathy, which has a similar physiological

abnormality, i.e. restriction of ventricular filling. Helpful in

the differentiation of these two conditions are right ventricular

trans-venous endomyocardial biopsy (by revealing myocardial

infiltration or fibrosis in RCM) and echocardiography, CT

scan or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (by demonstrating

a thickened pericardium in constrictive pericarditis but not

in RCM).

8

Our fourth patient (MN) actually presented this

challenge but a convincing thickening of the pericardium at

echocardiography was enough to help us clarify the diagnosis.

Another important problem is the lack of placebo-controlled

trials from which appropriate therapy may be selected, and

of guidelines that assist in important clinical decisions. As a

result, the practitioner must rely heavily on clinical judgment.

9

The absence of guidelines specific to this subset of pericardial

disease may be due to its relative rarity in the Western world.

The recent European Society of Cardiology guidelines on

management of pericardial diseases was also silent on the subset

of patients with effusive constrictive pericarditis, presumably

due to a paucity of data on the subject.

6

Other reasons could be

difficulty in reaching a diagnosis and varied aetiopathogenesis,

necessitating different evolution patterns.

While there is an abundance of diagnostic armamentarium

in the West, practitioners in sub-Saharan Africa largely have to

cope with severe limitations in diagnostic facilities. An exception

to this may be South Africa, where a recent report highlighted

the value of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) in delineating epicardial and pericardial inflammation in

effusive–constrictive pericarditis.

10

Cost is still an issue even if

MRI becomes widely available. Clinical acumen and reasoning

therefore still form the bedrock of clinical practice in most

centres.

The cases managed in this series illustrate this point. In only

two of the five cases was there a hint of constrictive physiology

at the initial echocardiography, even though it is known there is

a phase of transient sub-acute constriction, which may improve

after pericardial drainage and medical treatment, especially

with anti-tuberculous therapy in those arising secondary to

tuberculosis. The only strong evidence of a high likelihood of

need for pericardiectomy was the duration of the history in the

first three patients. They all had a history longer than two years,

suggestive of a chronic process.

Reaching an aetiological diagnosis is a real challenge globally

but more problematic in our local practices. The results of

pericardial fluid culture are frequently falsely negative and

pericardial biopsy has a higher yield of diagnostic specimens.

11-13

One therefore has to rely on pericardial tissue biopsymicrobiology

and histology. None of our patients had positive evidence from

pericardial fluid microbiology or cytology. The histology of

their pericardia is shown in Table 1. Three of the patients were

therefore treated empirically with anti-tuberculous therapy.

The difficulty in establishing a bacteriological or histological

diagnosis is foremost among unresolved issues in patients

with pericarditis.

14

A definite or proven diagnosis is based on

demonstration of tubercle bacilli in the pericardial fluid or on

histological section of the pericardium. A probable or presumed

diagnosis is based on proof of tuberculosis elsewhere in a

patient with otherwise unexplained pericarditis, a lymphocytic

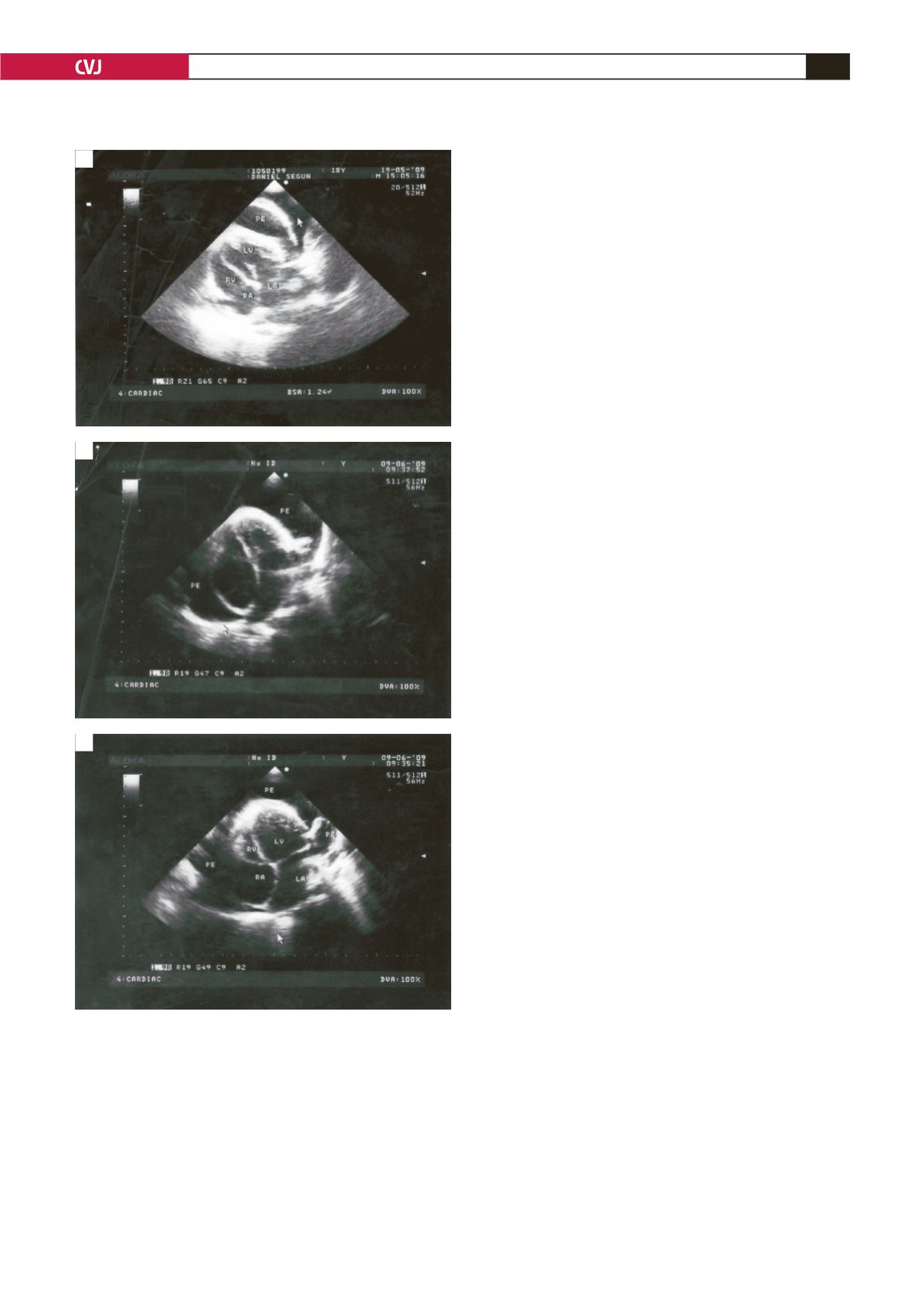

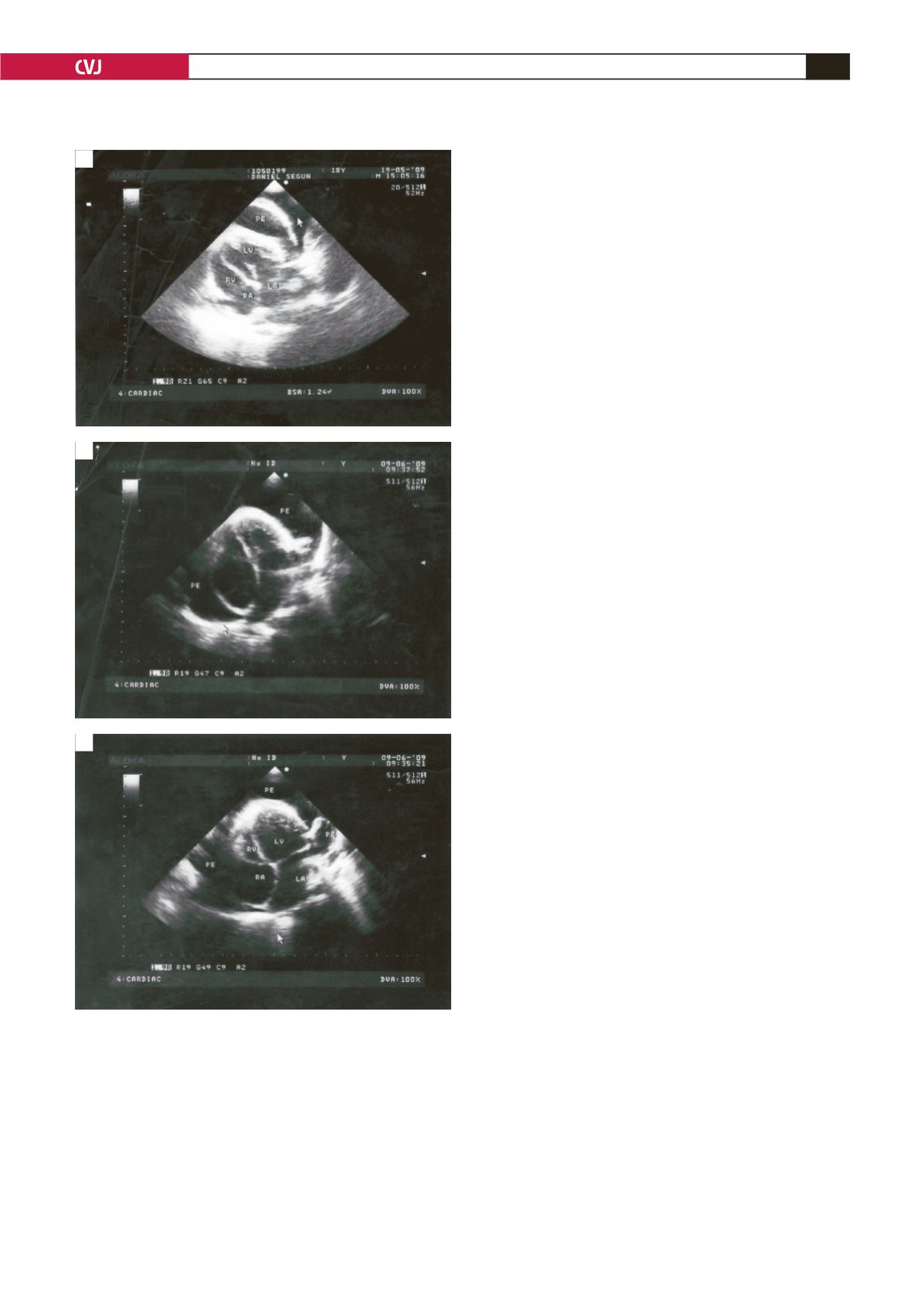

Fig. 4. Echocardiography showing moderate pericardial

effusion (PE). RV = right ventricle; LV = left ventricle; RA

= right atrium; LA = left atrium.

A

B

C