CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 2, March/April 2017

AFRICA

123

(Table 3). However, during the three years of follow up, only a

minimal contribution of COPD to aortic dilatation at the level

of the sinus of Valsalva was detected (Table 3). In patients with

diabetes, the expansion velocity was observed to be 0.4 mm/year,

being most marked at the level of the sinotubular junction.

Hypertension is known to be an independent risk factor

for aortic dilatation. In various studies, annual increases in the

diameter of the ascending aorta have been reported at 1.25 mm

in normotensive and 2.8 mm in hypertensive patients.

21

However,

since these patients are continually on drug therapy, it is difficult

to investigate the effects of uncontrolled hypertension on annual

expansion rates. In the presence of controlled hypertension and

diabetes, dilatation of the sinotubular junction and tubular

segments of the aorta was more frequently observed. In tractable

hypertension, annual dilatation rate at the level of the tubular

aorta was found to be 2.2 mm.

21

In our study, age demonstrated a significant correlation with

dilatation rates in both groups for all segments of the aorta,

excluding the aortic ring. Other risk factors made minimal

contributions to dilatation rates, with no statistically significant

differences (

p

>

0.05) (Table 3).

Various formulae have been developed to predict the

expansion rate of aortic aneurysms, but no correlation between

the determined and estimated size of the aneurysm could be

demonstrated.

22

Bonser

et al

. followed up the natural course of

aneurysms in their series and reported an annual aortic expansion

rate of 3.3 mm for 44-mm-dilated aneurysms associated with

thrombi, but without any evidence of stroke and TIA. The

annual expansion rate was 1.9 mm without the concurrent

presence of thrombi. In this series, decreased growth rates were

reported for larger aneurysms.

22

Similarly, segments proximal and distal to the aneuryms were

tracked in patients who had previously undergone aortic surgery,

and a decrease in expansion rate of the aneurysms to 1.18–1.59

mm/year was reported.

19

In our cases, annual expansion rates

differed in various aortic regions, while the tubular (mid-)

segment of the ascending aorta was the most dilated portion.

Irrespective of aetiological factors, the mean expansion rate of

this segment was 1.2

±

0.9 mm/year, which was similar to the

dilatation rate following AVR.

On TTE, measurements of the aortic diameter may

demonstrate individual differences. CT angiography has

a higher sensitivity and specificity for the ascending aorta.

However, in multi-slice sections, it is difficult to evaluate the

sinotubular junction and annulus. In addition to the higher

cost of CT angiography, the contrast material used carries

risks of anaphylaxis and renal toxicity. Therefore, we deemed

it appropriate to analyse our cases using TTE, which allows

evaluation of ventricular and valvular function.

Limitations

Pre-operatively, the aortic diameters of our patients ranged

between 40 and 45 mm. Since it is known that the expansion

rate decreases in proportion to the increase in aortic diameter,

we believe that comparative regression analysis between groups

of aortae with varying diameters would reveal a correlation.

Although our follow-up period was only three years, we obtained

values close to those cited in the literature. However, we are of

the opinion that in long-term follow-up studies (five to 10 years),

more significant and precise results would be obtained.

Genetic investigations were not done in our cases or in other

studies on this subject. When undertaking genetic investigations,

if patients with connective tissue disorders are grouped separately,

then the number of extreme values would decrease and these

groups would demonstrate a more homogenous distribution,

with similar effects on the outcomes.

Conclusion

In our three-year follow-up study on patients with ascending

aortic dilatation that did not require surgical intervention,

who underwent proximal anastomosis of the ascending aorta

and only CABG surgery, we detected significant increases

in diameters of the sinotubular junction and tubular aorta.

Since our study population was homogenous as far as the

demographic and clinical characteristics were concerned, and

their hypertension was under control, we believe that this

statistically significant postoperative increase in expansion rate

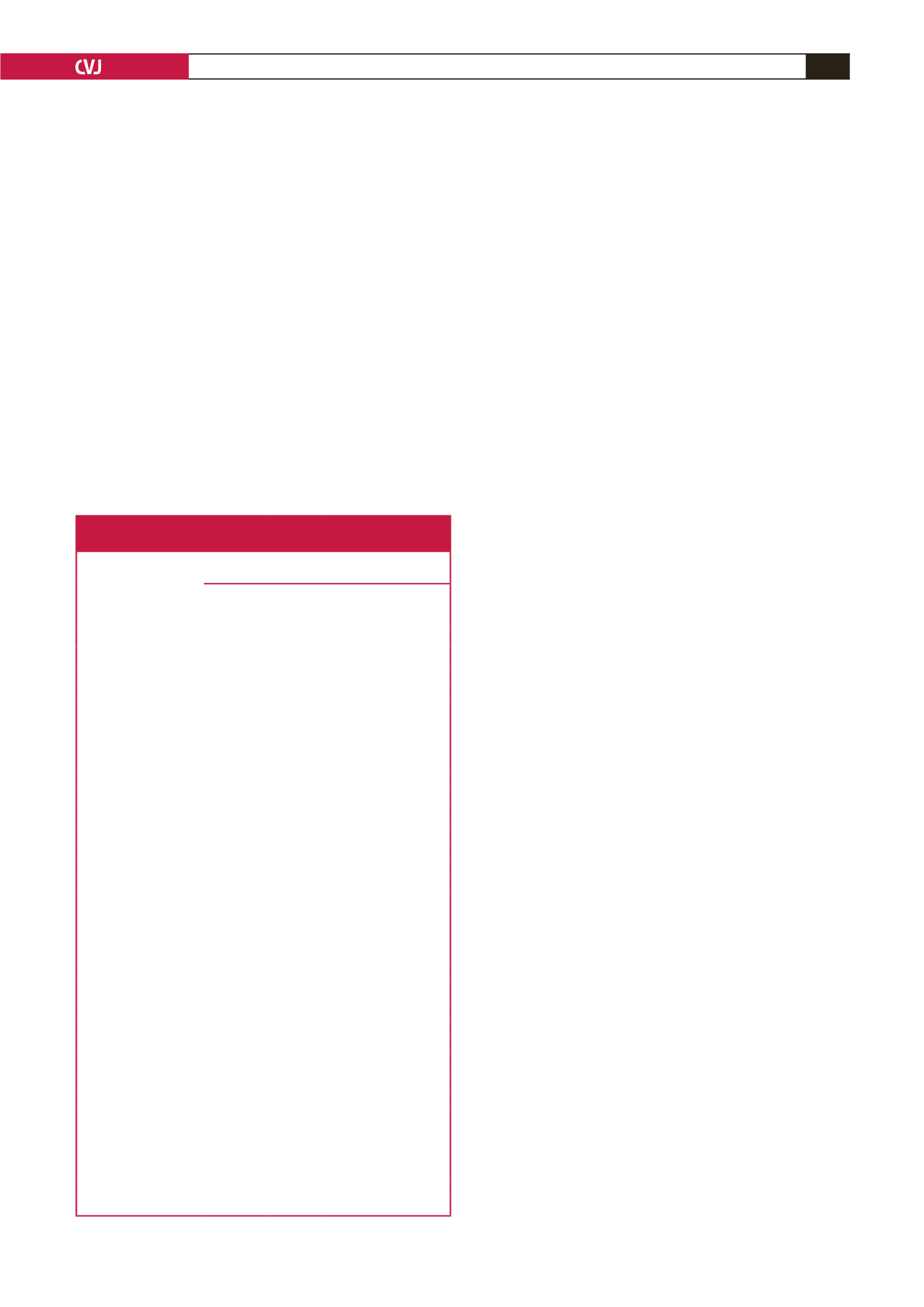

Table 3. The effect of pre-operative risk factors on changes in

aortic diameter at three years of follow up

Difference in diameter of the ascending aorta

(mm/3 years)

Aortic

ring

Sinus of

Valsalva

Sinotubu-

lar junc-

tion

Tubular

aorta

Hypertension

Present

1.27 ± 1.1 1.5 ± 0.37 1.5 ± 1.2 6.7 ± 1.9

Absent

1.1 ± 1.3 1.6 ± 0.38 1.1 ± 1.1 2.1 ± 1.7

p

-value

a

0.488

0.501

0.01

0.001

Smoking

Present

1.1 ± 1.2 1.6 ± 0.34 0.8 ± 1.0 3.7 ± 3.2

Absent

1.2 ± 1.3 1.5 ± 0.45 1.1 ± 1.1 3.3 ± 2.5

p

-value

a

0.756

0.163

0.004

0.793

Hypercholesterolaemia

Present

1.1 ± 1.3 1.6 ± 0.4 1.4 ± 1.2 3.0 ± 2.6

Absent

1.2 ± 1.2 1.6 ± 0.41 1.1 ± 1.0 3.7 ± 2.7

p

-value

a

0.852

0.401

0.222

0.97

Alcohol abuse

Present

0.75 ± 1.0 1.8 ± 0.3 1.1 ± 1.3 3.9 ± 3.0

Absent

1.2 ± 1.2 1.6 ± 0.4 1.2 ± 1.1 3.4 ± 2.7

p

-value

a

0.282

0.01186 0.745

0.540

Diabetes mellitus

Present

1.1 ± 1.2 1.7 ± 0.3 1.2 ± 1.1 3.3 ± 4.2

Absent

1.7 ± 1.7 1.6 ± 0.4 0.4±0.7 3.4 ± 2.6

p

-value

a

0.095

0.475

0.01

0.195

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Present

1.5 ± 0.7 1.6 ± 0.4 1.4 ± 1.0 3.1 ± 1.9

Absent

1.1 ± 1.3 1.4 ± 0.3 1.2 ± 1.1 3.4 ± 2.7

p

-value

a

0.295

0.032

0.233

0.755

Gender

Female

1.3 ± 1.0 1.5 ± 1.2 1.3 ± 1.2 3.6 ± 2.0

Male

1.4 ± 0.9 1.4 ± 1.1 1.2 ± 1.1 3.5 ± 2.2

p

-value

a

0.752

0.252

0.920

0.178

Beta-blocker (+)

Present

1.2 ± 0.0 1.4 ± 1.2 1.3 ± 1.2 3.0 ± 1.9

Absent

1.3 ± 0.0 1.5 ± 1.1 1.2 ± 1.3 3.9 ± 2.1

p

-value

a

0.190

0.082

0.178

0.098

a

Mann–Whitney

U

-test.