CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 2, March/April 2018

102

AFRICA

same day as patient visits (1/7), between one and seven days after

visits (5/7) or over seven days after visits (1/7).

The majority of sites had access to adequate resources for

conducting electrocardiograms (ECGs) and echocardiograms

(echos). Baseline echos were conducted on-site at 27/30

respondents’ sites and baseline ECGs were conducted on-site at

26/30 sites. While 26/30 respondents always or usually had access

to ECGmachines, 2/30 sometimes or seldom had access. Twenty-

five/30 respondents always or usually had access to ECG paper

while 2/30 sometimes or seldom had access.

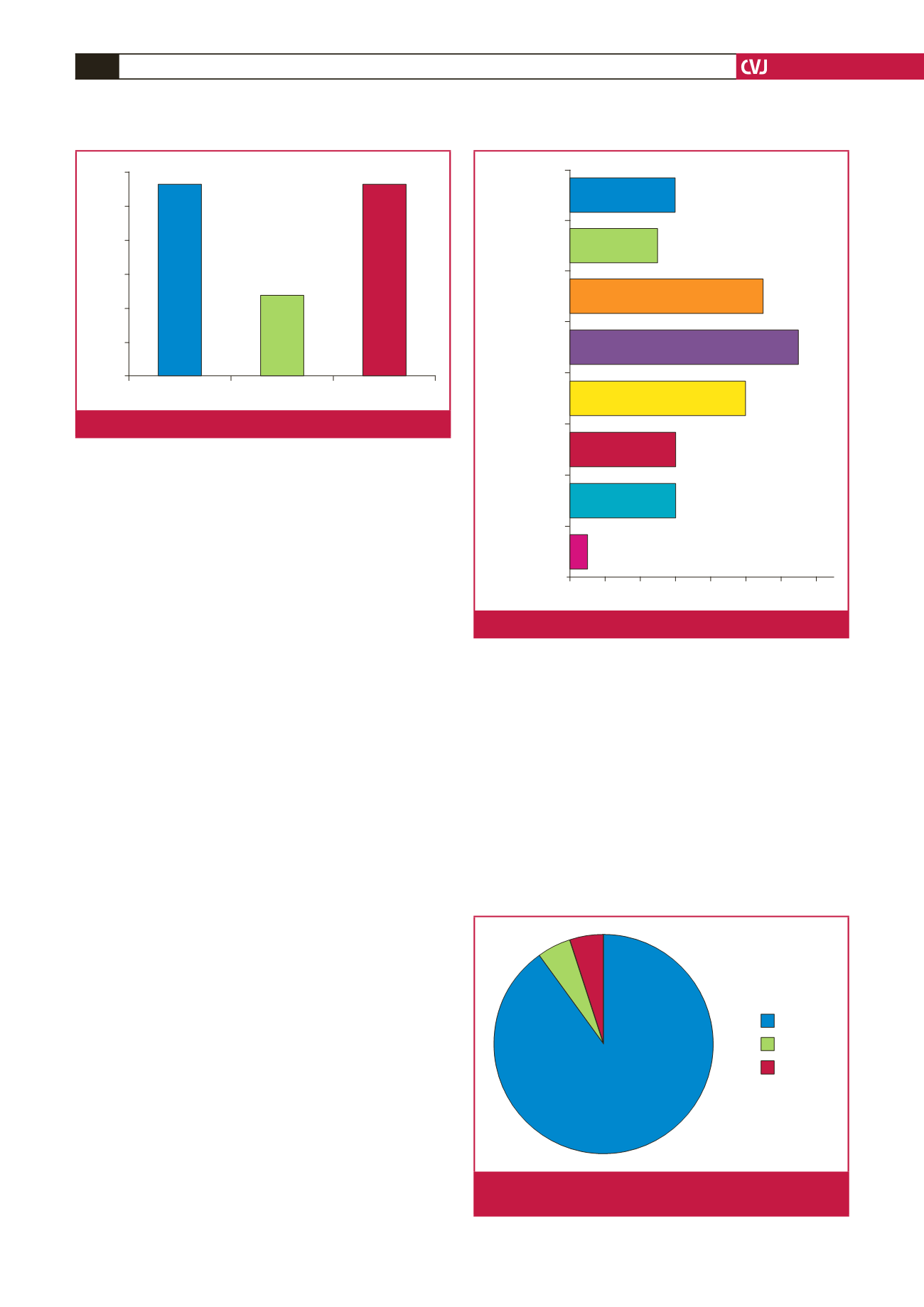

The majority of respondents experienced drug stock-out

problems for their RHD patients, including penicillin (19/30),

anticoagulants (17/30) and other cardiac drugs such as digoxin,

ACE inhibitors, spironolactone and captopril (19/30) (Fig. 6).

On-site internet access varied across sites. For example,

REMEDY e-mail was either provided by respondents’ work

facilities (15/30) or by personal devices and funds (13/30)

throughout the study.

Several sites purchased supplies for conducting the REMEDY

study. Items bought included telephones (6/30), computers (6/30),

airtime (10/30), scanners, copiers and fax machines (13/30),

patient binders, files and stationery (11/30), echo machines

(5/30), ECG machines (6/30) and other supplies not mentioned

in the survey (1/30) such as furniture. Seven/30 respondents did

not purchase anything for conducting REMEDY (Fig. 7).

Telephone interview

Clinical management: almost all responses (17/19) were positive

when asked whether participation in REMEDY changed their

management of RHD patients (Fig. 8). Changes included more

rigorous use of penicillin prophylaxis and anticoagulation,

increased efforts to reduce loss to follow up, establishment of

independent RHD clinics, more regular INR management,

higher-quality standards for echocardiography, improved

knowledge concerning early symptoms of RHD, and increased

efforts to provide family planning counselling to post-menarchal

females. For example, one participant remarked, ‘Before

REMEDY, we were not very keen on important interventions

like family planning and mandatory injections. REMEDY led us

to be more vigilant, to encourage family planning and to make

sure our RHD patients are getting regular medications. It has

improved the care for these patients’.

Research participation: for 15/19 respondents, REMEDY

encouraged further participation in rheumatic and congenital

heart disease projects and collaboration with researchers in these

fields. At least eight sites have continued working with REMEDY

investigators on subsequent studies (INVICTUS, RHDGen

and Afrostrep) while independent sub-projects have focused

on pre-school screening for RHD, atrial fibrillation, primary

prevention measures for RHD, and co-morbid associations with

hepatitis B.

10

Administration: results varied when participants were asked

whether participation in REMEDY changed administrative

structures at their sites. Some (5/19) stated that it changed

systems for the filing of patient records and recording the

ECG machine

Echo machine

Stationery

Scanner

Airtime

Computer

Telephone

Other

1

6

6

10

13

11

5

6

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Fig. 7.

Online survey: items purchased during REMEDY.

Penicillin

Anticoagulants

Other (e.g. digoxin)

Percentage of survey respondents

64

62

60

58

56

54

52

63.3

63.3

56.7

Fig. 6.

Online survey: drug stock-out problems.

90%

5%

5%

Impact

No answer

No impact

Fig. 8.

Telephone interview: impact of REMEDY on patient

management.