CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 27, No 4, July/August 2016

270

AFRICA

Cardio News

Frontline initiatives in early myocardial reperfusion with

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Concern has been expressed by leading

cardiologists in Africa about the lack

of preparedness of healthcare services

on this continent in relation to the

management of non-communicable

diseases and, specifically, cardiovascular

disease.

1

This may be attributable to a

paucity of surveillance data and registries,

a shortage of physicians and cardiologists,

interventional measures not being in

place, inadequate diagnostic capabilities,

and misguided opinions, as reported.

2

From the South African 2011 census,

3

we know that low household income

compounds the problem of inadequate

healthcare provision, and also lack of

transport to facilities where optimal care

can be provided timeously. Public sector

clinic services are utilised by 61.2% of

households, public hospitals by 9.5%, and

private hospitals, private clinics and other

services by only about 5% of households.

A disparity is evident between the health

facility used and the population group,

in that 17% of black South Africans

versus 88% of white and 64% of Indian

households visit private health facilities.

The Government report explains the

preference for private health institutions

by long waiting times and unavailability

of drugs in the public healthcare system.

However, of the total population, 41%

would be able to reach the health facility

normally used within 30 minutes, and

an additional 17% within 90 minutes.

Disparity is also observed among

population groups concerning coverage

by medical aid or medical benefit schemes

and other private health insurance.

The most recent report from a study

performed at a public academic hospital

in Pretoria in 2015 states that ‘Only 37%

of patients received fibrinolytic therapy

and only 3% received the medication

within one hour’.

4

Similarly, 44.7% of

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

(STEMI) cases reportedly received

fibinolytic therapy at the Groote Schuur

Hospital in Cape Town (2012),

5

and 36%

of South African STEMI cases captured

in the ACCESS registry (2007–2008)

received fibrinolytic therapy.

6

Baseline data for the STEMI Early

Reperfusion Project, undertaken in private

hospitals in the Tshwane metropolis (May

– October 2012) to establish time intervals

along the referral pathways from onset

of symptoms to percutaneous coronary

intervention (PCI), showed that system

delays were evident with inter-facility

transport (IFT) compared with direct

access (DA) to a PCI facility (median

3.7 vs 30.4 hours;

p

< 0.001). Door-

to-balloon times of ≤ 90 minutes were

achieved in a mere 22% of DA and 33%

of IFT patients, and fibrinolysis within

≤ 30 minutes was only achieved in 50% of

DA and 20% of IFT patients.

7

The South African Heart Association

EarlyReperfusion Project for ST-elevation

myocardial infarction commenced in 2012

as an initiative of the South African Heart

Association (SAHA), with Dr Adriaan

Snyders as president of the association.

The pilot study in the Tshwane metropolis

private sector

7

informed an observational

multi-centre study in South African

hospitals, launched in the last quarter of

2015, to identify factors that contribute

to delays in early reperfusion for STEMI.

A sub-study will be launched in 2017 to

investigate whether implementation of

a hub-and-spokes model (hub hospitals:

PCI-capable hospitals, and spokes: referral

hospitals), with the application of an ICT

(an ECG-capturing, patient-monitoring,

communication and data-capturing

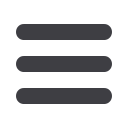

Declaration of intent to fulfil the Stent-for Life mission in

South Africa. From left to right: Dr William Wijns (SFL initiative

founder and past president of EAPCI), Prof Petr Kala (SFL

chairman), Prof Rhena Delport (SFL South Africa) and Prof

Stephan Windecker (president of EAPCI).

Signing the intent. From left to right: Prof Stephan Windecker

(president of EAPCI), Prof Rhena Delport (SFL South Africa)

and Prof Petr Kala (SFL chairman).