CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 23, No 10, November 2012

AFRICA

e3

than 10% whatever the form.

6

In our study, the incidence was

5.6%.

This frequency distribution is due to the heterogeneity in

definitions of pacemaker infection.

The factors predisposing to the occurrence of infection after

implantation of a pacemaker are diabetes, cancer, long-term

treatment with corticosteroids or anticoagulants, the presence

of postoperative haematoma, surgeon’s inexperience, and the

number of times the operation is repeated.

7,8

Other factors were

also implicated, such as the implantation of more than two

wires,

9

fever occurring within 24 hours of implantation, using a

temporary pacemaker, early re-operation,

10

and the placement of

the pacemaker box in the abdomen.

11

In our study, the risk factors found were: diabetes, dermatosis,

the long duration of pre-operative stay, the use of temporary

pacing, the number of people concurrently in the ward (between

four and five, average 4.5), postoperative haematoma and

repeating the operative procedure.

The mechanisms of infection were contamination of the

surgical site at the time of implantation

12

or haematogenous

spread from a remote focus, identified or not.

13

The average time

of onset of symptoms varied, according to the authors, between

six and 34.5 months.

14,15

We found the average time of onset to be

6.6

months in our study.

The clinical signs of infection of pacemaker varied according

to the location of the infected portion, from only localised signs

of a sagging in the pocket in about 70% of cases, local and

general signs in 20% of cases, to general symptoms in 10% of

cases.

16

The clinical presentation of infective endocarditis with a

pacemaker is right heart endocarditis with fever and pulmonary

symptoms secondary to septic emboli. None of our patients

showed signs of endocarditis but all had local signs of infection.

The microbiological diagnosis relies on sample collection

from a potentially infected site, repeated blood cultures, and

samples of different pre-operative implanted parts. In all patients,

a sample from the site of the pacemaker pouch was collected.

Staphylococcus

,

mostly coagulase negative, was involved in

50

to 90% of cases.

3

We found

Staphylococcus

in 80% of

cases, namely

Staphylococcus aureus

(40%)

and

Staphylococcus

epidermidis

(40%).

Moreover, mixed infections are not

uncommon. There can be associations of a staphylococcus with

other bacteria or fungi, or a combination of two different strains

of staphylococci.

17

The strong presence of skin bacteria is an

additional argument in favour of contamination during handling

of the pacemaker.

Echocardiography is the key to the morphological diagnosis

of endocarditis on pacemaker leads by visualising the

vegetations. Different morphologies of vegetations have been

described: floating ribbons, large rounded lesions, more or less

pedunculated, multilobed vegetations, and a sleeve around the

lead.

3

The sensitivity of transoesophageal echocardiography in

detecting vegetations is above 90% while that of transthoracic

echocardiography is above 30%.

13

In our study, no patient

received transoesophageal echocardiography. This would explain

the fact that we did not see any vegetations.

The management of pacemaker infection is difficult and has

been the subject of several studies. In infective endocarditis

secondary to pacemaker leads, all authors agree that removing

the implanted material is necessary for treatment.

18

On the other

hand, in local infections, opinions on how to treat are divided.

Some advocate conservative treatment

19

while others suggest

radical treatment.

17

However, current recommendations call for a

complete removal of implanted material in all types of infection,

whatever the clinical presentation.

19

In our study, we used conservative treatment and we had

four out of six recurrences. Mortality was one in six (16.7%)

patients. This highlights the importance of complete removal and

re-implantation of a new device or a sterilised, used pacemaker,

especially in our circumstances.

Conclusion

Infections secondary to pacemaker implantation are rare but

serious. The risk factors found were diabetes, dermatoses, longer

duration of in-hospital pre-operative stay, use of a temporary

pacemaker, the number of patients in the ward, postoperative

haematoma and re-operation. The management of infection is

difficult and can lead to removal of the implanted device. Hence

the importance of prevention, especially in our country where

pacemakers are still very expensive.

References

1.

Klug D, Balde M, Pavin D,

et al

.

Risk factors related to infections of

implanted pacemakers and cardioverter-defibrillators: results of a large

prospective study.

Circulation

2007;

116

: 1349–1355.

2.

Selton-Suty C, Doco-Lecompte T, Freysz L,

et al.

L’endocardite sur

matériel de stimulation intracardiaque.

Ann Cardiol Angeiol

2008;

57

:

81–87.

3.

Camus C, Donal E, Bodi S,

et al.

Infections liées aux pacemakers et

défibrillateurs implantables.

Med Mal Infect

2010;

40

: 429–439.

4.

Catanchin A, Murdock CJ, Athan E.

Pacemaker infections: a 10-year

experience.

Heart Lung Circ

2007;

16

: 434–439.

5.

Uslan DZ, Sohail MR, St Sauver JL,

et al

.

Permanent pacemaker and

implantable cardioverter defibrillator infection: a population-based

study.

Arch Intern Med

2007;

167

: 669–675.

6.

Kearney RA, Eisen HJ, Wolf JE. Nonvalvular infections of the cardio-

vascular system.

Ann Intern Med

1994;

121

: 219–230.

7.

Villamil Cajoto I, Rodriguez Framil M, van den Eynde Collado A,

et al

.

Permanent transvenous pacemaker infections: an analysis of 59 cases.

Eur J Intern Med

2007;

18

: 484–488.

8.

Sohail MR, Uslan DZ, Khan AH,

et al

.

Risk factor analysis of perma-

nent pacemaker infection.

Clin Infect Dis

2007;

45

: 166–173.

9.

Marschall J, Hopkins-Broyles D, Jones M,

et al

.

Case-control study of

surgical site infections associated with pacemakers and implantable

cardioverter-defibrillators

.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol

2007;

28

:

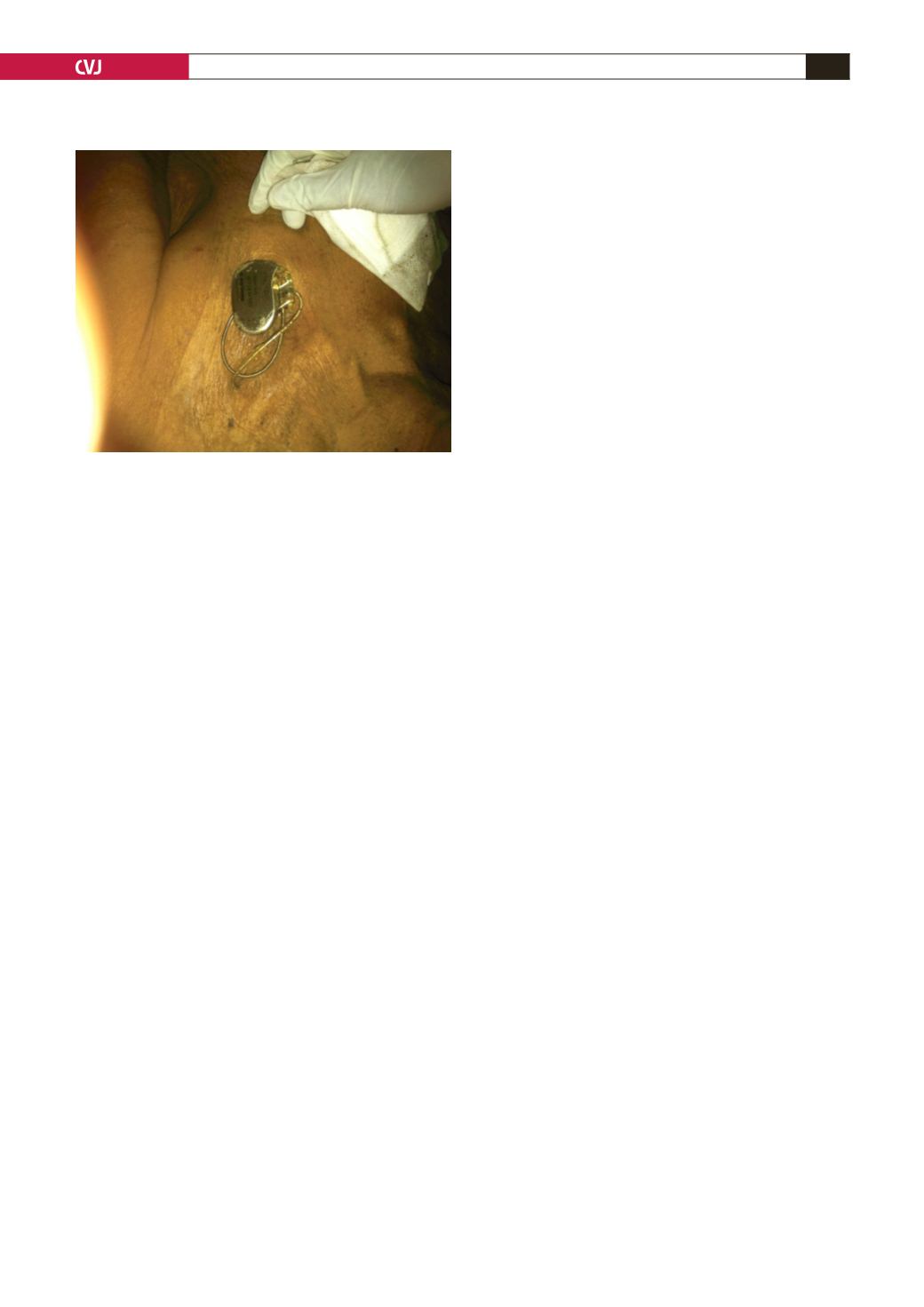

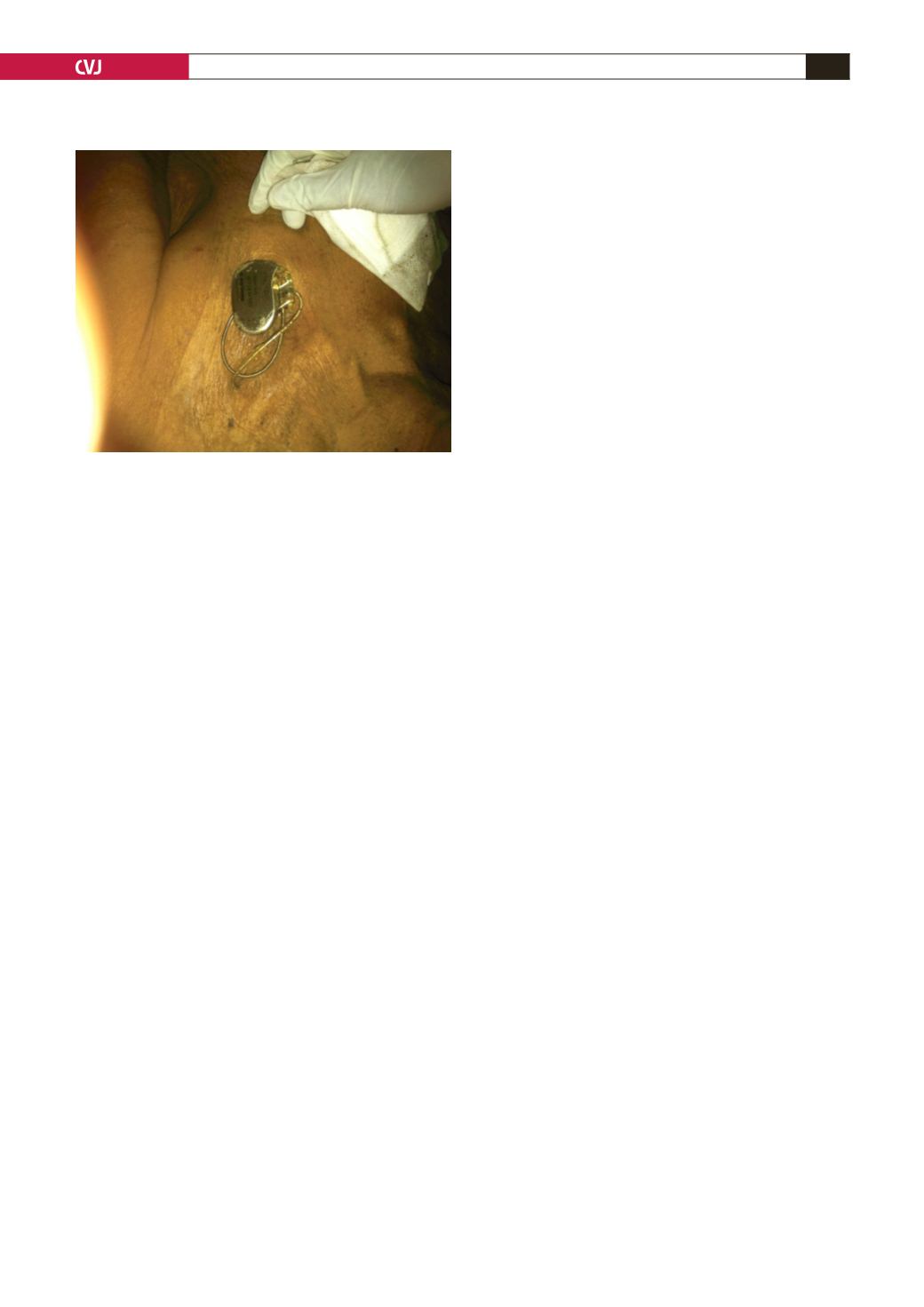

Fig. 1. Externalisation of the pacemaker pouch.