CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 23, No 1, February 2012

AFRICA

53

cular risk stratification in contemporary

populations with diabetes who are already

receiving many risk-reducing therapies.

It would be interesting if this acceptable

performance was demonstrated in other

validation studies, and that the uptake of

the model be shown to improve decision

making and the outcomes of care.

Dr AP Kengne

South African 2012 guidelines for hypertension therapy

Therapeutic options in hypertension management: 2012 guidelines from the Southern African

Hypertension Society

Introduction

This guideline should perhaps be called

SAHS 5,

1

in keeping with other hyperten-

sion organisations’ approach of regarding

guideline development as a continuum.

As new studies emerge, guidelines are

updated as a general reference for clinical

practice.

South African guidelines have been

issued since 1995,

2

with the first guide-

lines being endorsed by the Medical

Association of South Africa and the

Medical Research Council. The first

guideline was directed at achieving a

target blood pressure (BP) of systolic

(SBP) 140–159 mmHg and diastolic

(DBP) 90–94 mmHg, with minimal or

no drug side effects. Subsequent guide-

lines were issued in 2001,

3

2003

4

(partial

update), 2006,

5

and now the 2012 guide-

lines have been released, all targeting

blood pressure to lower levels of 140/90

mmHg.

Cost effectiveness has always been

a feature of South African hyperten-

sion treatment guidelines, but the new

2012 guidelines have adopted a different

approach to achieving cost effectiveness.

This is based on using an ‘evidence-based

approach to the estimation of cardiovas-

cular disease (CVD) risk and treating

those patients at highest or moderate

risk, and identifying those (at lower and

moderate risk) who can benefit most from

lifestyle and drug interventions at the

lowest cost, given the country’s limited

resources’.

In reviewing the development of

South African guidelines, it is clear that

they provoke considerable debate and

comment. A recent South African MRC

6

review of clinical practice guidelines

within the Southern African Development

Community notes that the South African

hypertension guidelines (reviewed only

up until 2006) are in high agreement

with current best evidence but noted the

poorer score in the ‘editorial independ-

ence domain’, reflecting on the poor

reporting of potential conflicts of inter-

est of participating experts. The authors

in this Medical Research Council study

note that ‘Although the absence of these

declarations does not necessarily imply

that inappropriate influences guided the

final recommendations, the presence of

such declarations ensures that a guideline

can be considered trustworthy’.

Rationale for cardiovascular risk

assessment

As this guideline seeks to place effec-

tive treatment in the realm of managing

individuals with the greatest potential

to benefit from treatment, cardiovascu-

lar disease risk assessment is pivotal.

The guideline recognised that interna-

tional risk-assessment systems and charts

do have shortcomings, particularly with

regard to developing countries such as

South Africa.

It bases these guidelines, until a

national consensus on a different model

emerges from all stake-holders (profes-

sionals, providers, government and

healthcare funders), on the risk strati-

fication from the ESH/ESC guidelines

7

(Table 1). Using this risk stratification,

the Guideline Committee has developed

a management flow diagram, cited as an

adaptation from the WHO cardiovascu-

lar disease risk-management approach

for low–medium resource settings (Fig.

1). The definition of major risk factors,

target-organ disease and associated clini-

cal conditions (ACC) is adapted from the

current ESH/ESC guidelines (Table 2).

Considerable guidance is given in

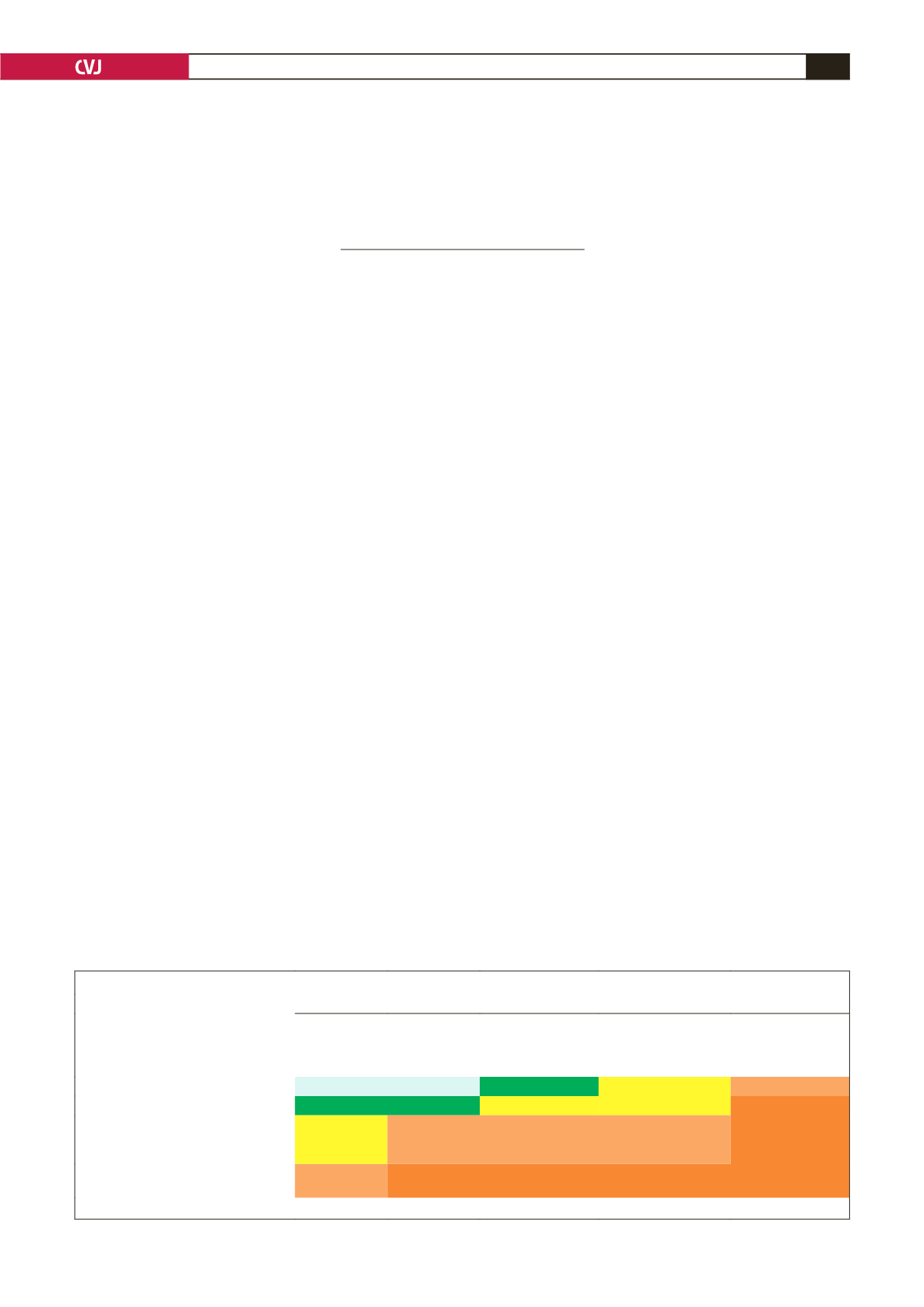

TABLE 1. STRATIFICATION OF RISKTO QUANTIFY PROGNOSIS*

BP (mmHg)

Other risk factors and disease history

Normal

SBP 120–129

or DBP 80–84

High normal

SBP 130–139

or DBP 85–89

Stage 1

Mild hypertension

SBP 140–159

or DBP 90–99

Stage 2

Moderate hypertension

SBP 160–179

or DBP 100–109

Stage 3

Severe hypertension

SBP > 180

or DBP > 110

No other major risk factors

Average risk Average risk Low added risk Moderate added risk High added risk

1–2 major risk factors

Low added risk Low added risk Moderate added risk Moderate added risk Very high added risk

≥

3 major risk factors or target-organ

disease or diabetes mellitus or

metabolic syndrome

Moderate

added risk

High added risk High added risk

High added risk Very high added risk

Associated clinical conditions

High added risk Very high

added risk

Very high added risk Very high added risk Very high added risk

* Based on the ESH/ESC guidelines.